This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE 1955 landmark Bandung Conference is still having a major impact on international foreign policy thinking nearly 70 years later.

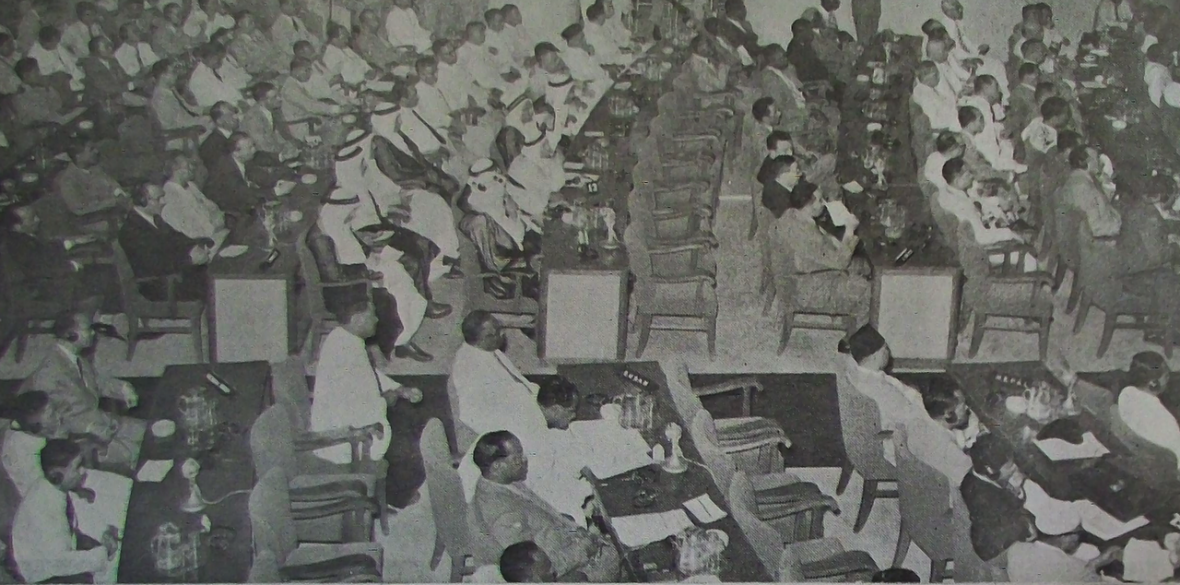

The conference, held in Bandung, Indonesia, brought together representatives from 29 African, Asian and Middle Eastern countries in one of the first major transnational expressions of opposition to racism and colonialism.

Participants at Bandung represented countries such as Egypt, China, India and, of course, Indonesia.

These nations believed their interests were best served by not formally aligning themselves with either the US or the USSR.

Representatives demanded an end to the nuclear arms race and a fundamental message was how little the manoeuvring of the superpowers meant to the nations of the global South — or how much it delivered for them.

Nations struggling to develop their economies, improve healthcare systems and, for many, freeing themselves from the yoke of racism and colonialism, wanted to forge their own paths and make their own decisions based on their own interests and not those of the superpowers.

Bandung did not just appear out of nowhere. There were two earlier conferences of these non-aligned nations in Bagor, Indonesia — in 1949 and 1954.

The second Bagor conference in 1954 set up Bandung to give the global South — or as it was increasingly being dubbed the Third World — a voice away from the superpowers in the UN and elsewhere which were completely dominated by the US, the USSR and the colonial powers.

But it was about more than securing a seat and a voice at the master’s big table. It was an assertion of the independence of countries representing around a third of the planet to forge relationships with whomever they wanted and whenever they chose to do so.

The 10 principles agreed at Bandung called for respect for human rights, respect for sovereignty, equality, non-intervention in the internal affairs of other nations, right to self-defence, and abstaining from collective defence arrangements.

They also agreed to refrain from acts or threats of aggression, the peaceful settlement of disputes, co-operation between nations and respect for justice.

Bandung inspired the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in 1961 in Belgrade.

Although the NAM tried to stay away from cold war power plays, this was never a fully realisable possibility.

The political and material support by the USSR for anti-colonialism led the US and their allies to accuse NAM of being a front for the USSR — which was never the case.

The US particularly feared that nations which had just been freed from colonial rule might become more attracted to socialism. While some nations chose a socialist path, others did not. Indonesia, for example, was involved in the deadly suppression of communism within its borders.

The US was extremely hostile to Bandung and the NAM. As far as it was concerned you were either fully with them in the fight against communism — or you were against them. For them, neutrality at the height of the cold war was essentially support for communism.

The 120 countries of NAM remain the largest grouping of states worldwide after the UN. There are several other regional initiatives that champion South-South co-operation and solidarity.

These include the African Union, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (Celac), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation among many other initiatives.

The recent initiative by Celac to develop its own regional currency to break away from the dominance of the US dollar shows the ambition to chart an independent global South course is still alive and well. In Celac, Brazil and Cuba in particular are playing important roles in these initiatives and through them in a revitalisation of the Bandung spirit.

The continued relevance of Bandung can even be seen in the recent peace plan put forward by China to bring an end to the war in Ukraine.

China’s 12-point plan looks remarkably similar to the 10 Bandung principles including its emphasis on an end to a “cold war mentality” and the respect for national sovereignty.

The Bandung spirit of unity, friendship and co-operation is being carried forward by China through policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative as a means of strengthening global co-operation and promoting peace.

The Bandung spirit is still important because it treats seriously the notion that countries of the South have the agency to collectively tackle the impacts of globalisation.

Whilst we have seen major advances by the likes of China, India and Indonesia, globalisation has created major social and economic inequalities in the global South.

The co-operation of countries in the global South frees them from the dominance of the US to begin bilateral or multilateral discussions to share experiences of countering the global movement of capital, investment, goods and ideas.

This freedom is no insignificant matter.

It allows for an understanding that the immense wealth of natural resources can be used by and for the people of the global South and is not there for the continued exploitation of the US and the former colonial powers.

It’s a freedom that also creates a new self-confidence amongst the people of the global South. After so many years of being labelled as inferior through periods of slavery and colonialism and their aftermath, the development of a new self-consciousness allied to a developing understanding of the power of the collective creates a powerful force that breaks away from the physical and mental order established by the slavers and the colonialists.

Following Frantz Fanon in Wretched of the Earth, I am not talking about “a crude, empty, fragile shell” of national consciousness. I talk instead of a mental starting point for our liberation from the oppression we, the global majority, have experienced.

Liberation does not begin until all of us — whether from or within the global South — understand our worth and our ability to collectively build a new world.

Bandung and the NAM provided us with an important starting block. It’s now up to the rest of us to continue to run the race.

Roger McKenzie is the Morning Star’s International Editor. Follow him on Twitter @RogerAMck.