This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

BY THE 1680s, the law lay bleeding in England. City charters had been withdrawn and rewritten, political trials had broken the opposition to the Stuart crown, and a vast standing army was assembled upon Hounslow Heath in order to keep London down.

A new generation of young and highly ambitious lawyers, schooled in the ultra-royalism of the civil wars, had risen to prominence in the service of the restored monarchy and had offered their skills and rapier-like intelligences in the achievement of spectacular political gains through the control of the legislature and the law courts.

Foremost of these was Judge Jeffreys, who rose to become lord chancellor and whose name still resonates with cruelty in the West Country, whose rebels he hanged or transported as slaves to the Americas and the West Indies.

Absolutism was within a king’s grasp. Yet, the integrity of the law was to be maintained and enhanced, through the creation of recognisable civil liberties, through a series of radical innovations by judges such as Sir John Holt (1642-1710), who effectively subverted and limited the power of the crown.

Nowadays, Holt is far from a household name and does not rank with Haldane, Thompson, or Loseby in the pantheon of left lawyers.

This is because his progressive role has been obscured for a number of reasons. He did not turn his hand to the writing of legal treatises; the compilations of his trial rulings are heavy, stodgy materials that make no mention of his judgements on witch trials and occlude his progressive attitudes towards domestic violence, militarism, and slavery.

At the height of the Tory reaction of the 1680s, his politics seem — purposely — opaque. On the one hand, he was prepared to support the assaults of the crown upon the Whig corporations but, on the other, he defended both ordinary political activists and political grandees alike.

To defend Lord William Russell on the charge of treason, brought by a vengeful monarch in the wake of the collapse of the popular movement, required some considerable reserves of courage, self-belief, and resource. Perhaps, most seriously of all, though, Holt is forgotten simply because he lacks a modern biographer.

Yet his contemporaries were in little doubt as to the scope of his achievements in the defence of the “Lives, Rights, Liberties and Properties of the People.”

Holt had lost his position as recorder of the city of London in 1686, after saving the life of a soldier discovered asleep at his sentry post by establishing the point that while the king might press soldiers into service during peacetime for his rapidly expanding army, through the use of the royal prerogative, he could only subject them to civil as opposed to martial law until the outbreak of war.

The ruling effectively meant that James II could not discipline his conscripts and struck at the ability of the crown to maintain a standing army that was independent of parliamentary scrutiny.

Similarly, in 1705, he delivered a verdict that curtailed the possibility of the growth of the slave trade in England itself. The case revolved around a black slave, purchased in Virginia and brought to England, who was then to be re-sold in the London Parish of St Mary le Bow.

Holt ruled that the laws of colonies became void in England, and that as soon as a black person set foot in England, they became free as “one may be a Villein in England, but not a Slave.”

This created the possibility that if an African slave could manage to jump ship and reach shore, she or he could obtain their liberty.

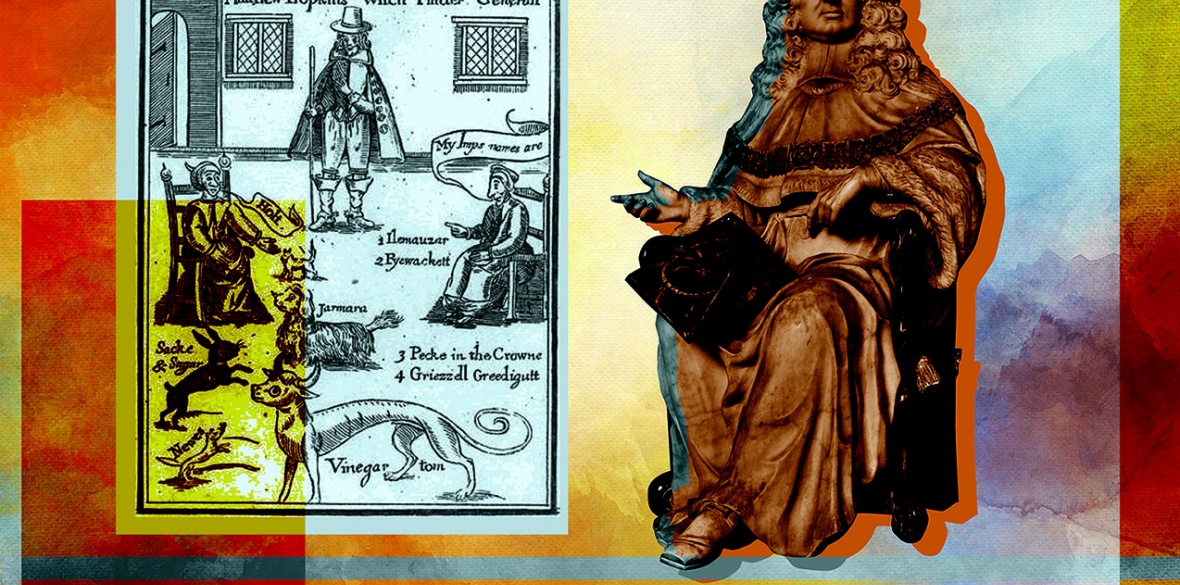

In a similar fashion, if the history of witchcraft often seems like a dismal catalogue of misogyny, double-dealing and cruelty, then it is also worth remembering that it was illuminated by rare and decent individuals — such as Sir John Holt — who were prepared to break with prevalent opinion, self-interest or intellectual fashion and to embark upon courses of action solely because they believed them to be right.

In July 1701, long-running tensions boiled over between Richard Hathaway, a young Southwark apprentice who believed himself bewitched, and Sarah Moordike (or Morduck), the aged wife of a Thames waterman from the same parish.

Moordike was a quiet and inoffensive woman of good character, who had been accused of bewitching the blacksmith and of breaking his health over a period of more than a decade.

If her neighbours seemed to think well of her, then the juvenile street gangs on the Southside did not and Hathaway — who seems to have envisaged himself as a populist hero, in the mould of a modern-day Raoul Moat or the leader of a suede-head gang — possessed a ready charisma and had the mob, and a number of clergymen, on his side. Thus, before Easter 1701, he determined to take the law into his own hands.

Cornered and almost lynched, Moordike was bloodied, beaten and had clumps of her hair torn out when her house was stormed.

Escaping to the City of London, she was pursued across the Thames by Hathaway, who, with the apprentices at his back, broke into her new lodgings beside Paul’s Wharf, repeatedly drawing blood from her, scratching her face and arms in order to break the supposed curse placed upon him.

With a band of soldiers looking on approvingly and with the connivance of both parish constables and London aldermen, she was then strip-searched for “witches’ marks” or supernumerary teats.

Cut, battered and bruised, Moordike was committed to prison, charged with witchcraft and left there for several months, with bail refused, to wait upon the sitting of the assizes.

Yet Moordike’s trial did not go to plan. Holt, as the presiding judge, did not attempt to directly address the question of belief, or disbelief, in witches.

While the witchcraft Acts remained on the statute book, he could not directly challenge the laws of the land. What he could do, however, was to bend and circumvent the letter of the law in order to deliver an acquittal.

Thus, he chose to concentrate upon the medical evidence surrounding Hathaway’s supposed possession and his role as a fraudster.

He was helped in this by the extraordinary bravery and fortitude shown by Sarah Moordike herself, who, despite her beatings, retained her composure in order to deny everything that was laid against her.

This enabled Holt to secure a swift acquittal despite a popular outcry against “both judges, and jury, and witnesses.”

However, there was a further sting in the tale. Sir John Holt in his judgement intended to go far further than a simple acquittal of the suspected witch.

He ruled that all of her fees should be paid and that her accuser should be arrested and locked up in the Marshalsea prison, on charges of perjury for “pretending himself to be bewitched,” while his accomplices were to be imprisoned and charged with common assault.

This was a strong and unexpected action that challenged the ability of malicious persons to bring charges of witchcraft and effectively broke the power of the mobs on the South Bank of the Thames.

In March 1702, Holt sat in judgement once again. This time, upon the case of Hathaway. The case appears to have combined all those elements — namely, the privatisation of violence by the mob, the disorder and swagger of military men, domestic violence and the irrationality of witch belief — that the judge seems to have hated most.

As a consequence, Richard Hathaway was given an exemplary sentence as a warning to other “Cheats and Impostors.” He was ordered to pay a fine of 100 marks, to stand in the pillories in Southwark and the City of London, and then to be whipped at the house of correction, where he would serve a sentence of six months’ hard labour.

Consequently, the two trials overseen by Holt in July 1701 and March 1702 proved highly significant verdicts in the history of witch persecution in England.

They registered, respectively, not just the acquittal of an accused witch but the prosecution and punishment of her persecutor as a deterrent to others who might have been tempted to levy similar charges in the future.

If the European witch trials are often used to demonstrate the cruelty and prejudices of individuals and host societies, then it is also worth pausing a moment here to consider that they might also, as in this case, reveal something of the hard-nosed will required in order to obtain justice, to break the tyranny of the crowd, and to establish a new age in which an enlightened reason might flourish. Sarah Moordike and Chief Justice Holt, it seems, needed no lessons in that.

You can read the full story in John Callow’s book The Last Witches of England: A Tragedy of Sorcery and Superstition (Bloomsbury Press). Praxis is the name of Callow’s new Morning Star column.