This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

ULTRA-LEFTISM is a generally pejorative term applied to groups or individuals on the political left whose activities and slogans are prejudicial to the immediate interests of working people and which don’t contribute to the longer-term prospects for achieving socialism.

It is important to distinguish the term from “far left” which is generally used by the right to denigrate any organisation or individual whose politics are to the left of the Labour Party.

Today the term “ultra-left” is particularly applied by Marxists to policies and actions that overestimate the “revolutionary” potential of the working class at a particular time and fail to take account of existing conditions and the chances of success or the consequences of failure.

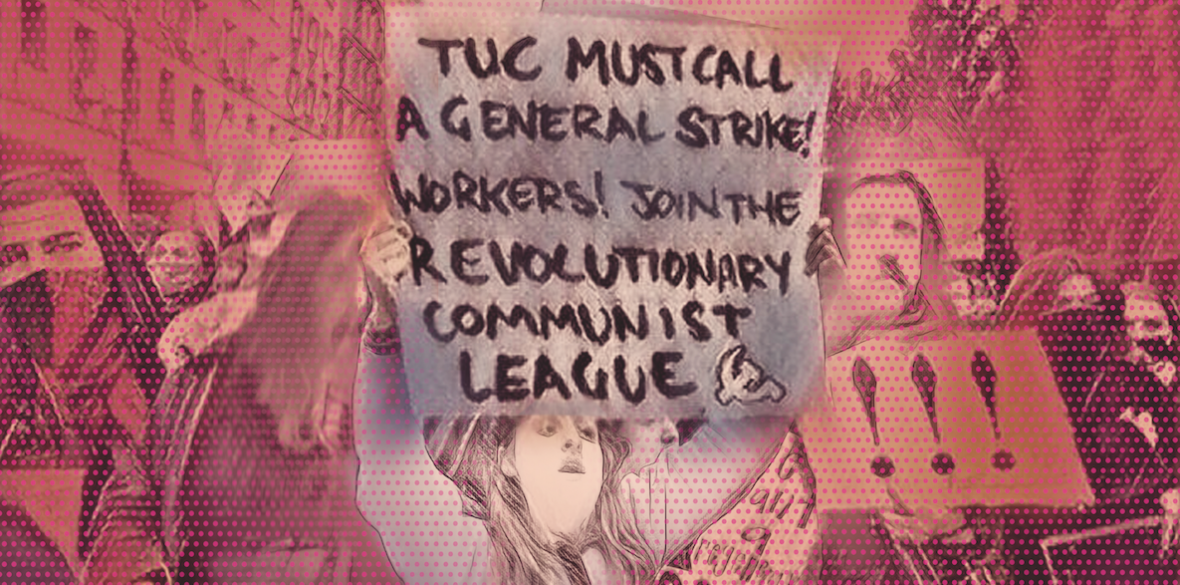

A classic example is the call for a “general strike now” irrespective of the chances that call has of being adopted by a broad section of the labour movement — or of the costs to individuals and left organisations who do act on it but are defeated.

Alongside this is a “politics of purity” characteristic of many who argue against membership of, or co-operation with, social democratic parties (such as the British Labour Party) and against participation in parliamentary or local elections.

This is often accompanied by sloganising, a dogmatic assertion of “correct” theoretical positions and left sectarianism — a dismissal of, and refusal to work with, other left organisations with similar aims, often on doctrinal grounds.

Most ultra-left groups argue that countries which claim or have claimed to have established socialism have only created “state capitalism,” ignoring the circumstances of their revolution and the problems of survival against external threats.

Importantly, ultra-leftism is often opportunistic. Whether working within the trade unions, community organisations, the women’s liberation movement or anti-racist campaigns, ultra-left activists do so in the first instance, not primarily to further the objectives of these organisations and their members, but to co-opt them to the broader goals of social(ist) revolution.

Ultra-leftism comes in many shapes and sizes. Anarchism seeks to leap straight to a classless, stateless society without any transitional period and ignores the need to build a mass revolutionary consciousness and an organised labour movement, often substituting direct action by individuals.

Then there are small, clandestine armed groups — examples from the 1970s include the bank robberies and bomb attacks against US military facilities and the right-wing press by the Red Army Faction (also known as the Baader–Meinhof group) in Germany, and the 1978 kidnapping of Aldo Moro, former Italian prime minister and leader of the centrist Christian Democracy party, by the Red Brigades (Brigatte Rosse).

Such actions alienate ordinary people and provide the pretext for the state to introduce repressive measures against the broader left.

They can also be identified with, or slide into, fascist terrorism, as with the 1980 Bologna massacre where 85 people were killed and over 200 wounded by a bomb planted in a railway station.

In some at least of these instances, there is evidence that ultra-left organisations were infiltrated and their actions encouraged by security services.

However, it would be wrong to label all forms of direct action as “anarchist” or as ultra-left. Direct action has always been one of the forms of resistance against the excesses of a capitalist state — from blockades of US air bases and nuclear facilities to the activities of groups such as Occupy and Extinction Rebellion.

These can serve at the very least to draw attention to issues which would otherwise be ignored by the media, and they can provide hope and inspiration to many who would otherwise see themselves as powerless.

At the other end of the spectrum is what has been termed the “blackboard socialism” of the Socialist Party of Great Britain and its breakaway groups (which oppose both Leninism and reformism) together with more recent attempts to replace, or establish electoral alternatives to, the Labour Party.

Such organisations consider participation in parliamentary elections a form of revolutionary action in itself. Examples include the Respect party (established in 2004 following Tony Blair’s 2003 invasion of Iraq) which united a range of anti-war and left groups including the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

Before it split in 2016, Respect secured significant electoral successes, including local councillors and an MP, George Galloway, who went on to form the Workers Party of Britain in 2019.

Another group standing against Labour in elections is the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition.

Debate continues — particularly among existing and recent Labour Party members — about the relative merits of “staying in” what has, since its formation in 1900, been the major electoral party of the left, or leaving to form yet another left party to contest elections.

The solution for the majority of Labour Party members who consider themselves Marxist will depend on local circumstances and on the possibilities of building the movement for change outside as well as within Labour Party structures.

In between the above are groups claiming inspiration from various revolutionary leaders and intellectuals such as Mao Zedong and Leon Trotsky.

While many Trotskyist groups today might be considered “ultra-left,” by no means can all ultra-left groups be described as Trotskyist. As an earlier Q&A argued, it is important to distinguish Trotsky the individual and his views from those political groupings claiming his name.

Trotskyist groups share a combination of features. One is a commitment to “permanent revolution” in opposition to those who believe that every country has to find its own road to socialism and that it is possible to secure in them at least the first stages of transition.

Another is what John Kelly calls “an unparalleled record of political failure,” coupled with a belief that the working class (often defined narrowly using the term “proletariat”) is inherently revolutionary, that the main obstacle to revolution is “revisionism,” that failure to secure it is due to “betrayal” (by those, including communists, who have managed to organise in their workplaces or communities) and by a constant, essentially opportunistic emphasis on the need for a new “revolutionary leadership” for any kind of progress to be secured in existing society.

Ultra-left demands, political and economic, are put forward not with the intention or expectation they might be achieved but because they cannot be achieved without directly challenging the structure of a capitalist state — “transitional demands.”

Ultra-leftism can be defined as the failure or refusal, in the name of abstract “left” principles, to engage with the difficult task of building and maintaining a mass movement to confront the realities of a capitalist system. It means, to use Lenin’s terms, not finding the next link in the chain — and so losing hold of the chain as a whole.

It means aspiring revolutionaries indulging their subjective wishes in place of any assessment of the balance of class forces at any particular time, ignoring the prospects for advancing working-class interests and thereby needlessly widening the gap between the organised left and the majority of the population.

At the same time, it is important to be aware that the use of the term “ultra-left” changes over time. There were times when socialists who championed the rights of women and ethnic minorities or who focused on issues such as the environment (which are today central to socialist politics) were labelled ultra-left.

“Ultra-left” individuals and groups have often made valuable contributions to broader struggles; examples include the campaign against the poll tax and today’s Stop the War Coalition.

Today, Britain faces increasing attacks on the living standards and conditions of ordinary people the Labour Party leadership continues its witch-hunt of the left, severing its links with the organised labour movement.

In this new phase of intensified class struggle the responsibility of all genuine socialists is to build the broadest possible alliances to challenge capitalism and grow the movement for a better, socialist, society.

That is a challenge to us all.

The Marx Memorial Library and Workers School’s rich programme of on-site and online seminars continues on June 8 with an examination led by Richard Burgon MP of Tony Benn and Labour’s 1973-74 programme for “an irreversible shift of wealth and power in favour of working people.” Visit www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk for more information.