This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

UGLY scenes outside Parliament have made the place look and feel like the Siege of Troy. But around the country bigger issues already fill the landscape.

A “climate emergency” conference in Lancaster drew in some 200-300 local authority and climate groups (along with similar numbers live-streaming their way in).

All were anxious to talk about existential survival. I’ve done similar meetings recently in Norwich, North Notts, Stroud and Hebden Bridge — each making the same point: it is climate change that most threatens our children’s prospects, not Brexit.

It isn’t that Labour leaders haven’t attempted to address this. They’ve just struggled to get press coverage for the bigger issues.

Jeremy Corbyn tried to do so at the Scottish Labour conference; putting climate, poverty and 50,000 “green jobs” at the centre of Labour’s offer.

John McDonnell did the same, throwing his support behind Momentum’s Boycott Barclays disinvestment campaign (over the financing of oil extraction pipelines from Canada’s tar sands).

Shadow transport secretary Andy McDonald made an awesome commitment to set carbon budgets for each part of the transport sector. But press coverage was brief and shallow.

At least shadow environment secretary Sue Hayman got rousing cheers from the Lancaster conference after making Labour the world’s first major national party to declare a climate emergency.

Denialism rules, OK.

Sadly, none of this has even made it onto the radar of “Leave Means Leave” supporters.

Climate denial has become wrapped up in a wider weave of denialism that dominates Conservative benches in Parliament, and which terrifies many on the Labour ones.

The country is both mesmerised and infuriated by Parliament’s Brexit debacle. As a result, all the major parties will get something of a kicking in the local elections about to take place.

Moreover, the possibility of a love tryst between Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn incensed Labour and Tory loyalists in equal measure.

It would be a loveless marriage. Far better to admit that Parliament is gridlocked. So put the choices back to the public. At least we could then address some of the absurdities wrapped up in the “Just jump,” “We’re British” and “We made it through the war” proclamations that currently make us all look idiots.

The war, the war, the war

Having been heckled by some of the Ukip/Britain First protesters, I have to admit that “the war” isn’t a bad place to start. It is the mantra used to dismiss warnings from the Bank of England, the CBI, major manufacturers and all sorts of economists, that a no-deal Brexit would be an economic disaster.

Once you start to praise such protesters for their commitment to the “conscription” and rationing needed to get us through such a period, much of their enthusiasm quickly wanes.

Not too many of the protesters seem willing to be part of the Land Army Britain would need, to plant spuds, carrots and grains to feed the nation.

Not many are keen on dawn cow-milking shifts, rescuing sheep from snowdrifts, or long days of harvesting. Yet as things stand, Britain only has three to five days of emergency food stocks. Some 70 per cent of our food (and two-thirds of our food carbon footprint)

comes from other people’s lands.

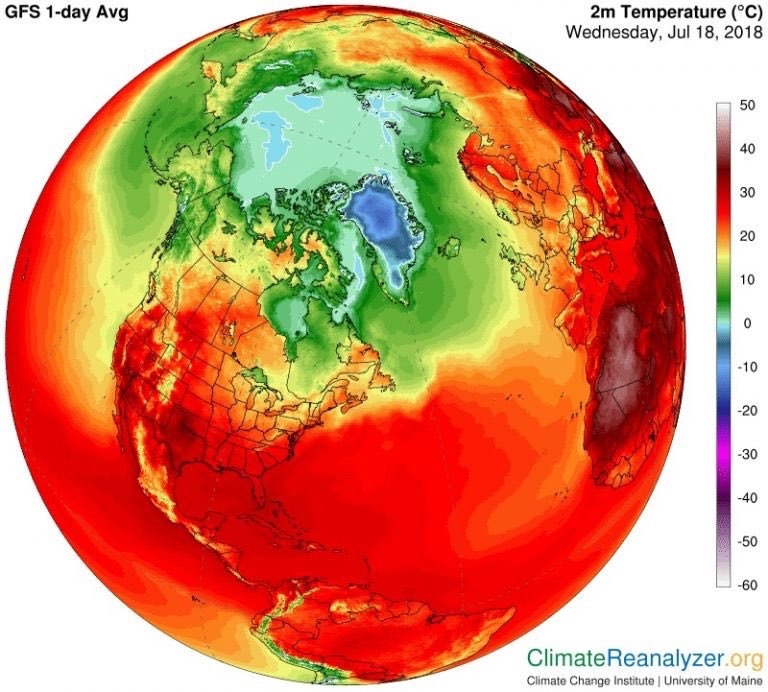

Last year’s erratic weather has already caused a 50 per cent fall in UK potato crops and a 30 per cent fall in most other root crops. Add in the mega queues any no-deal Brexit would produce and we are all likely to face conscription into a latter day “Dig For Victory” movement.

Such work might be good for us, but I couldn’t find much enthusiasm for it among the protesters; especially after pointing out there wouldn’t be much choice once we’d sent all those foreign workers home.

The Emperor’s climate clothing

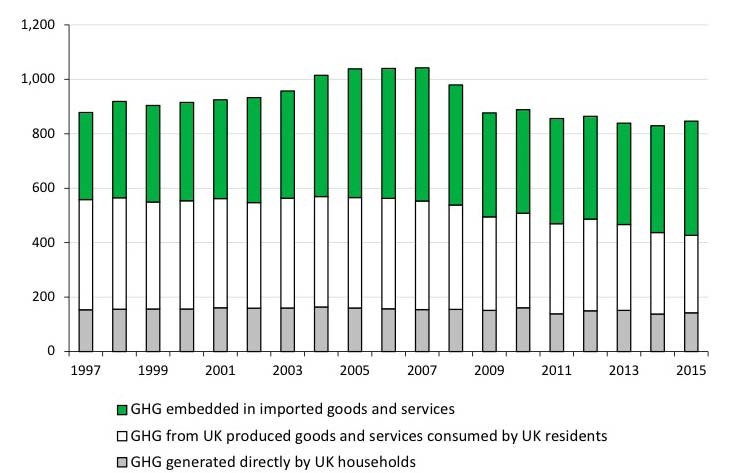

Food isn’t the only part of the British economy that needs a rethink once you move from Brexit to climate. We would then have to face up to our biggest national lie; that Britain has been leading the world in reducing carbon emissions since 1990. Defra has already spilled the beans on this — though no-one likes to mention it.

Each year, Defra publishes details of UK greenhouse gas emissions.

What they show is that UK households produce a low, but static, part of total British emissions. Emissions coming from goods and services actually “produced” in the Britain have genuinely fallen — largely because Britain has collapsed its productive sector in favour of cheap imports.

And it is in the 31 per cent increase in carbon emissions from imports that Britain hides it’s real footprint. Put them all together and you have an almost zero reduction in British greenhouse gas emissions since 1990.

My dad used to say: “Any idiot can run down an economy. You just sell off whatever you’ve got. The question then is: what do you live on afterwards?”

That’s where Britain has ended up; a nation that has come to believe it can just shop its way from one crisis to another.

Today’s crisis means the entirety of economics needs to be re-thought, in both productive and carbon terms. Ironically, this may also be the space in which Brexiteers and Extinction Rebellion might usefully meet up.

Britain has to cut its carbon emissions in half within a decade just to avoid climate breakdown. In doing so we’ll need to work out how to feed, clothe and reskill ourselves within a more sustainable economic framework. And such a framework will have to make sense in those parts of the country that were once the cornerstones of the industrial revolution but have become today’s industrial wastelands.

Plan B for Planet A

Burnley, Blackburn, Halifax, Scunthorpe, Hartlepool, Stoke, Bridgend, Dundee and 100 other towns and cities across the land have to be at the roots of the green revolution. They don’t trust Parliament to take them there any more than they trust Brussels.

In crude terms, the green revolution will only work if it is also a democratic one; rebuilding lines of democratic accountability and inclusion, from the grassroots upwards.

This is where Corbyn and McDonnell’s oft-repeated mantra — democratisation, decarbonisation and decentralisation — acquires its deepest meaning.

Rapid reductions in our carbon footprint will also require the relocalisation of production. You can’t hide the carbon footprint of shifting large quantities of goods around the planet by shovelling it under the carpet, as though it doesn’t exist.

We need to focus on moving the money around before we send people and goods chasing after it. The technologies that allow us to do so may be super smart and new but the structures for doing so can be built around our forgotten histories.

Two hundred years ago, towns and cities led Britain’s industrial revolution. Hundreds of them formed their own municipal gas and water and electricity companies. Municipal bonds were used to finance municipal utilities, and the profits went into building the public parks, museums, libraries and swimming baths we used to open (rather than shut down).

They also provided the energy that powered the production of goods and clothes that the economy was built upon. Today we can do the same, but in a more circular, clean and sustainable way.

Today’s energy system is horrendously inefficient. Two-thirds of electricity is lost in transmission between the power station and the plug. But across Europe “smart grids” already deliver (clean)

local energy to local communities, at almost half today’s grid prices, and with a minimal amount of lost energy.

Britain’s 750,000 homes with solar roofs currently save over 700,000 tonnes of carbon. So why not raise this to 7.5 million homes, and build our own network of smart grids? There’s lots of jobs, skills and clean energy to be found there.

A new ‘industrious’ revolution

It doesn’t stop with smart grids. Britain’s annual imports include 12.3m tonnes of iron ore. But we also produce 10m tonnes of scrap iron and steel, 70 per cent of which gets dumped abroad. Recycle this, in a revived iron and steel industry, and you again cut the hidden carbon footprint of imports; especially if the heat produced is then fed into district heating schemes.

But today’s green revolution has to be more industrious than industrial.

A more circular economy has to learn to share things more effectively. Research for the Green Alliance has shown that creating “Libraries of things” could save Britain 6.5 MtCO2e a year just by sharing the goods we have. Extending the lifetime of products could save a further 13.5 MtCO2e, and improving their design (making them repairable) would save another 12.7 MtCO2e per year.

Don’t worry if, to begin with, these numbers make little sense. Like energy efficiency ratings on fridges, we will quickly grasp the difference between a light carbon footprint and a heavy one. But to the planet (and our children) it will mean a lot.

All this carbon saving clocks up, even before we start putting carbon back — through the restoration of peat bogs, community-scale tree planting, and the greening of towns and cities. And every part of the process can bring jobs and skills, hope and solidarities back into the abandoned landscapes that had once made Britain prosperous.

The Wastelands end when hope and power, dreams and democratic control are given back to people. Then abandoned towns and cities become the drivers of change; building the truly “green and pleasant land” our children might yet live in. It’s what real politics is all about.

Alan Simpson is former MP for Nottingham South and currently advises Labour on environmental policy.