This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

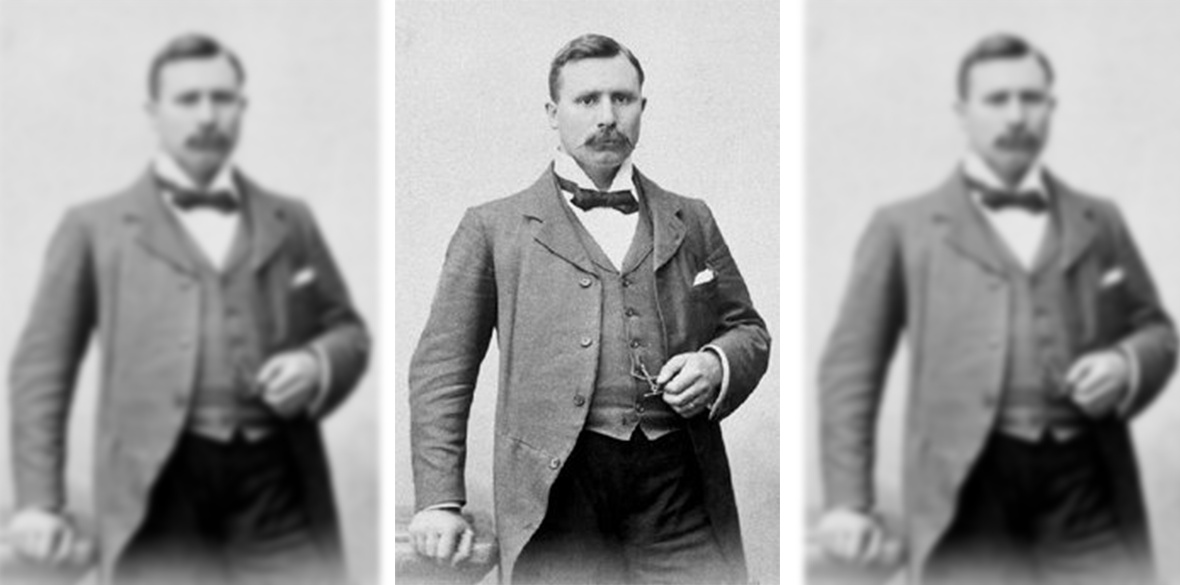

TOM MANN was born on April 15 1856 at Bell Green, Foleshill, Warwickshire, just outside Coventry.

His mother died when he was two and he left school at nine to work in the fields, then in coalmining aged 10 to 14, in conditions once described as “near medieval,” where his father was a colliery clerk.

A colliery fire, common in those days, resulted in Mann leaving work to be “bonded” to a tool-making firm in Birmingham where he worked a 60-hour, six-day week, with “frequent working of two hours’ overtime of an evening with no penalty rates.”

His generation had no possibility of political representation. In 1867 the then Conservative prime minister, the Earl of Derby, established a royal commission on trade unions, which led to the legalisation of trade unions through a Trade Union Act in 1871.

The early growth of British capitalism across the globe rested on the textile trades but this was giving way, mid-century to the export of metal goods.

At the centre of the Midlands lay the metal workers who, along with the coalminers, became the intellectual engine of the British working class.

Early influences

As a toolmaker craftsman — those some Marxists refer to as a labour aristocrat — Mann was among those who were pushing against all the boundaries placed on them.

They expected to be taken seriously in political life, live in habitation that was secure and clean, and took an interest in culture, technology and science.

Their union ticket was a sign of stature as well as solidarity. Mann records attending a different night school every day of the week save one. He had catching up to do. As a young man he had only attended school for three years, but the appetite for learning burned strongly in him.

In his memoirs he writes: “Although I was connected with the Anglican Church, the Bible class I attended and liked so much was conducted by Edmund Laundy of the Society of Friends. Mr Laundy was a public accountant, a precise speaker, a splendid teacher. He taught me much, and helped me in the matter of correct pronunciation, clear articulation, and insistence upon knowing the root origin of words, with a proper care in the use in the right words to convey ideas.”

The church taught Mann about the power of unity, which he took into his union activism.

At this point it is true to say that Mann was not uncommon among inquisitive and often self-educated working craftsmen of the period.

The study of history, given great importance by Marx, is often to be found at the cultural core of socialist political activists of Mann’s generation.

It is in the study of history and in no other branch of foundational knowledge, that socialists come to understand and validate their world view, the evolution of societies and ideas, from primitive communism to modern socialism.

By 1884 Mann took part in his first proper strike. He had come to believe that those who toiled the land should own it. Those who produced should own the product of their labour.

He believed in an eight-hour day, then a major concern of all trade unionists. An eight-hour day would lighten their burden, but he saw in it a schema for reorganising society based on eight hours for work, but also eight hours for rest and eight hours for education and the restitution of family, community and working-class life.

First clashes

1886 is a key year in Mann’s life. He entered the struggle over unemployment which had grown steeply among trade union members after 1882, when it had averaged 2 per cent. By 1886 it was over 10 per cent. This of course records unemployment among skilled trades and the condition was much worse for those employed in semi-skilled and unskilled work, which dominated in the ports.

There emerged in London a full-frontal struggle for power between the police, led by police commissioner Charles Warren, and radicals led by the Social Democratic Federation, the Socialist League and the Labour Emancipation League.

Before they could make the case against unemployment, it was necessary to secure the right to speak in public at all. So, radicals engaged in free speech struggles and agitation for the relief of the unemployed across London, but especially just south of the Thames and in the East End.

When blocked by the police, they would encourage the unemployed to go to churches and join with their own banners on church parades to make their presence known.

Mann was present at the Bloody Sunday demonstration the following year when Alfred Linnell was murdered by police. It was in the middle of these tumultuous times that the workers in London were beginning to flex their electoral muscle and take advantage of the legislation brought forward by William Gladstone.

Mann invoked William Morris when he claimed that five centuries past, “without machinery, Englishmen obtained for their work sufficient to keep them in vigorous health … the working day then consisted of no more than eight hours.”

Such was the power of the popular memory about the Elizabethan labour laws, which fixed wages, working hours and prices of basic foodstuffs (the cost of meat, for example, didn’t change for over 100 years).

What had changed was industrialisation and the domination of the profit system allied to the introduction of “labour-saving” machinery, which to employers saved on wages at the expense of workers’ jobs.

The eight-hour day issue separated the old unions from those trying to organise new ones.

The way he wielded the eight-hour day, to alleviate the worst excesses of capitalist exploitation and to free up time for enlightenment, runs in tandem with the notion that an eight-hour day is a completely new way of ordering society.

It was also in 1886 that he “gladly accepted the name of Communist from the date of my first reading of The Communist Manifesto, and have ever since been favourable to Communist ideals and principles.”

This article is abridged from Phil Katz’s new biography of Tom Mann, Yours For the Revolution, published by Manifesto Press (www.manifestopress.coop).

Manifesto Press are embarking on their first summer speaking tour, WELL READ. WELL RED. Tickets can be reserved at linktr.ee/manifestopresscoop.

Phil Katz is a designer and writer and has been a union organiser for 40 years. He contributes regularly to the Morning Star.