This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Salted Wounds

Mohammed Moussa, Drunk Muse Press, £10

ONE small side-effect of Israel’s genocidal response in Gaza to the Hamas atrocities of October 7 is to thrust Gazan poets forward. At a time when Palestinians are being dehumanised and murdered with the support of Western powers, when Israel is destroying hospitals, schools, universities, the need to hold on to the common culture of the people becomes a more urgent one.

Possibly the best-known Gazan poet is Mosab Abu Toha, who was kidnapped by the Israeli army as he fled to southern Gaza with his family last week, and then released — after a beating — due to international pressure. However, he is just one member of the Gaza Poets Society (see https://www.facebook.com/gazapoetssociety/), that brings together 32 young Gaza poets. That was set up by fellow poet Mohammed Moussa, and it is Moussa’s collection, Salted Wounds, published in July this year, we review here.

Moussa grew up in the Jabalia Refugee Camp, in the north of Gaza, now largely levelled, and its inhabitants killed or driven out by the Israelis. He had already become an exile in Turkey before the current slaughter – remember, though very much the worst, this is far from the first Israeli bombing attack on Gaza and its population. The title of the collection comes from a poem that tells us: “In Gaza, salt heals/ our grandparents put salt/ on their untouched cuts,” but asks “Why salt doesn’t heal since I left.”

For the exiled poet, recreating the images, scents, sounds of their homeland is a way of recreating it. Moussa uses simple but vivid language to evoke Gazan life, threaded through with military brutality but also with beauty, love and friendship. He tells us “The girl I fell in love with smells like wisteria,” speaks of “the lost midday on the roof of our house in northern/ Gaza, the smell of fresh ground cardamom in my coffee.”

But he also writes of the 10 minutes Israelis give for evacuation before they bomb a house to the ground and the life-memories you have 10 minutes to hold in your head before they do: “the letter from your exiled brother,/ the smell of the bed,/ the ring you bought for your wife,/ your old dress,/ your favourite teacup...”

And of course he writes of the bombs, that “rain down on the city/ like hellbats in the early hours;” and the random murders of children: “Gaza is a lonely mother/ sitting on the beach/ where her four sons/ once played football” – referring to a well-known atrocity.

Moussa speaks of the effort it takes to resume life after each bout of attacks: “As I get used to the smell of blood and the images of broken glass/ and martyrs, I train my memory to live normally...”, of how “Twenty-two paintings follow me as I walk along the shore” – the members of his own family who have been killed. And the pain of exile: “I don’t want my memories to grow old on foreign soil.”

The poet WH Auden famously wrote that “poetry makes nothing happen” and yet if it enters hearts and gives readers the ability to imagine how it is for an exiled poet of Gaza, how it has been for the people of Gaza for so many years, that is not quite nothing. Drunk Muse have done us all a favour by making this work available, and yes, you should read it.

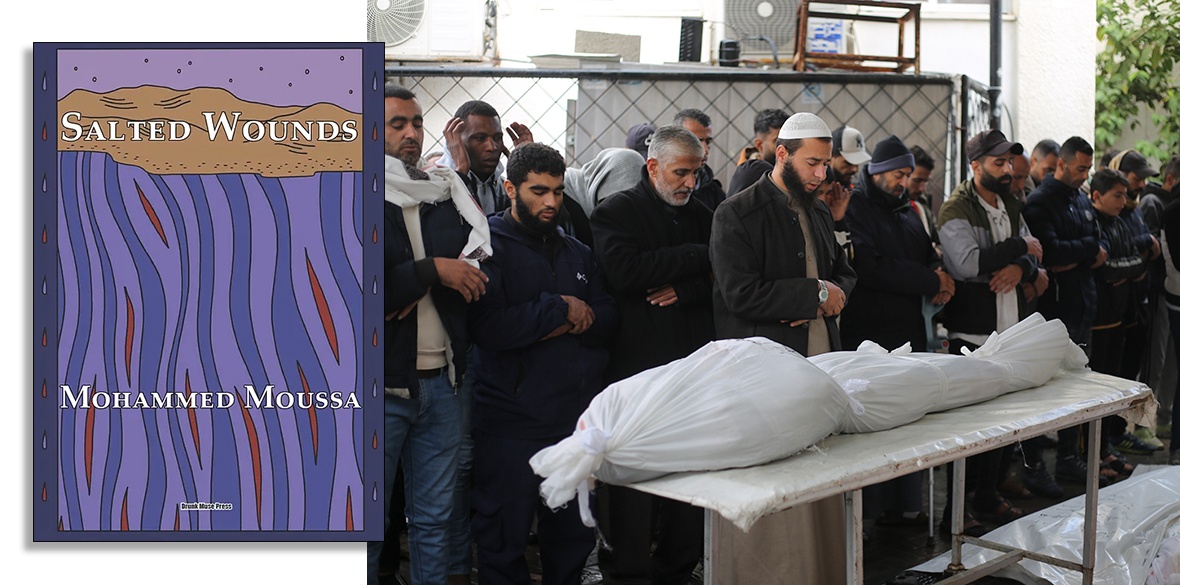

Palestinians pray for people killed in the Israeli bombardment of the Gaza Strip in Rafah on Wednesday, December 13 2023

Hatem Ali/AP