This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

AFTER Nelson Mandela was released from 1991 in preparation for the formal interment of the apartheid system, he embarked on a world tour to thank governments and peoples who had supported the South African freedom struggle.

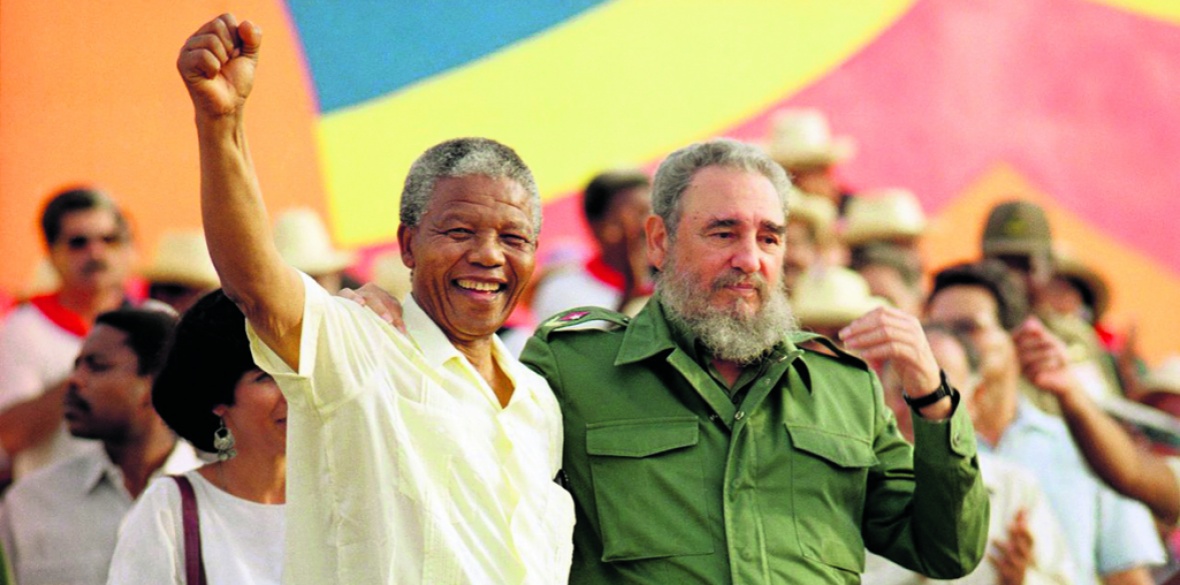

In Havana he extolled Fidel Castro as a “source of inspiration to all freedom-loving people.”

Later in the US, during the Ted Koppel show in front of a live TV audience, Mandela was questioned by neocon diplomat and political analyst Ken Adelman, asking whether Fidel Castro — and for good measure — Muammar Gadaffi and Yasser Arafat, the Libyan and Palestinian leaders, were “your models of leaders of human rights.”

Mandela responded: “One of the mistakes that political analysts make is to think that their enemies should be our enemies. That we can and we will never do.”

He added that these US bugbears had supported “our struggle to the hilt … They don’t only support it in rhetoric. They are placing resources at our disposal to win the fight.”

Cuba’s internationalism had already impressed itself on him when serving a life sentence on Robben Island and heard of Cuba’s military intervention in Angola in 1975 in support of the MPLA liberation government against the apartheid South African invaders who were closing in on the capital Luanda.

Mandela told a rally in the Cuban city of Matanzas that Africans were “used to being victims of countries that want to take from us our territory or overthrow our sovereignty. In African history there is not another instance where another people has stood up for one of ours.”

He understood that “to the Cuban people internationalism is not only a word but something which they have put into practice for the benefit of large sectors of mankind.”

The South African liberation leader pointed out that, when the African National Congress and its allies had decided they were left with no alternative but to take up arms against the apartheid dictatorship, they had approached Western governments but were fobbed off with meetings with the lowliest officials.

“When we visited Cuba, we were received by the highest authorities who immediately offered anything we wanted and needed,” he recalled.

Fighters from the South African liberation movement’s armed wing uMKhonto we Sizwe (MK) testify to the unstinted quality of the training, including intelligence gathering, they received in Cuba.

They were able to put that knowledge to good use in the MK training camps in Angola, which Cuba’s 1975 solidarity action had prevented from being overrun for the invading apartheid forces.

If 1975 was a joint enterprise with the Soviet Union, which transported the internationalist troops and heavy equipment, Cuba’s second, and yet more decisive, supportive intervention that led to the epic battle of Cuito Cuanavale in 1988 was Havana’s alone.

The Soviet Union made clear that it was opposed to a military intervention, seeking a diplomatic accord with the US to end South Africa’s assistance to its Unita allies who risked being defeated in their Jamba stronghold, in south-east Angola, by the People’s Liberation Armed Forces of Angola (Fapla) and its Cuban comrades.

In response, the Cuban Communist Party central committee agreed on November 1987 to send 9,000 crack troops, together with the most modern tanks and warplanes, to Angola to put paid to the apartheid regime’s domination of South Africa’s front-line states.

Without fanfare they crossed the Atlantic and, as the world stood watching in anticipation, engaged the apartheid forces, suffered grievous losses but prevailed, forcing Pretoria’s withdrawal from both Angola and Namibia and paving the way for Namibia’s independence and for negotiations to abandon the apartheid system and bring democracy to South Africa.

Many anti-imperialists saw parallels between Cuito Cuanavale and a similar pivotal battle 45 years earlier, Stalingrad, that marked the decisive turning point against another tyranny that denied humanity’s unity, espousing racial superiority.

Unable to accept the idea of defeat by an overwhelmingly black foe, South Africa’s top brass claimed Cuito Cuanavale as a victory, citing tendentious figures of losses of personnel and equipment on each side, but, as with Stalingrad, the bitter fruits of defeat stared the master race in the face.

They retreated, while the Fapla forces, supported by the Cuban internationalists and units from MK and the Namibian liberation forces Swapo, celebrated their victory.

Mandela spoke of Cuito Cuanavale as “a turning point for the liberation of our continent and my people.”

The selfless role of the Cubans and the significance of their sacrifices to South Africa is attested to by a monument in Pretoria’s Freedom Park where the names of 2,070 who died in Angola are recorded alongside martyred MK volunteers.

As MK head of intelligence, and later intelligence services minister in an ANC government, Ronnie Kasrils put it, “After 13 years defending Angolan sovereignty, the Cubans took nothing home except the bones of their fallen and Africa’s gratitude.”

Cuba’s support for South Africa has continued in the almost quarter-century of democracy, taking thousands of young people to the island’s medical and research facilities — including the legendary Latin American School of Medicine — that have made possible Cuba’s deserved reputation for medical excellence and for solidarity through which around 55,000 Cuban medical personnel are currently serving in 67 countries.

Brazil’s far-right new president Jair Bolsonaro has achieved notoriety by ordering out 8,000 Cuba medical professionals, condemning countless poor Brazilians to poor health and neglect and the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) plays a similar role in South Africa.

The DA claims the ongoing scheme for sending medical students to Cuba for five years, before they return for final training of 12-18 months, is a “waste of money,” claiming it would be better spent at home.

According to South African Committee of Medical Deans Martin Veller, the biggest challenge for returning students — 720 this year, 800 next — is how to integrate these students into medical schools at home in such large numbers.

However, he declared that students returning from Cuba have integrated well into the healthcare system, especially at primary healthcare level.

KwaZulu-Natal Health Minister Dr Sibongiseni Dhlomo doesn’t share the pessimism of the DA, calling this year’s return “very exciting. It is very humbling. You could see the parents crying tears of joy.”

He insisted that South Africa’s National Health Insurance, which focuses on primary healthcare, would benefit from the students’ expertise.

“These students, coming back as doctors trained in Cuba, are driven by that as a way of life — primary healthcare, health promotion, health education, prevention of diseases, all of which is exciting for us as South Africa,” said Dhlomo.

“We are hoping that we are going to turn the corner, thanks to them.”

And Cuba’s ambassador to South Africa Rodolfo Bentez Verson stressed the qualitative difference between international aid and international solidarity, explaining: “The co-operation between our two countries is for the benefit for our peoples. It is not for the enrichment of individuals or transnational corporations.

“It does not seek the prosperity of the few or to obtain economic advantages for our countries. It is a model of South-South co-operation based on genuine solidarity.”