This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

July 1918 brought more war along the long line of the Western Front, where one newly wounded British soldier-poet with a record of adventurous bravery and a German forename was Siegfried Sassoon.

He received a head wound from accidental fire from a fellow soldier when returning from a patrol on July 13. Just published was his poetry collection Counter-Attack and Other Poems.

One item included the following verse, which was to become famously symbolic of the war.

“‘Good-morning; good-morning!,’ the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of ‘em dead,

And we’re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

‘He’s a cheery old card,’ grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.”

Sassoon, in a letter to the Times the previous year, had blamed the government for unnecessarily prolonging the war. He was not the only British soldier to distrust his commanders and war politicians, but his military service history helped to rule out his prosecution for “inciting disaffection.”

Those imprisoned for conscientious objection to military service continued to face harsh treatment. On July 20, five days after yet another resumption of Germany’s offensive in the West, the pro-war but humanitarian-inclined New Statesman summarised the situation of the “conchies” after addressing the latest reported CO death in custody — that of JG Winter, a miner and a socialist.

Winter had died of double pneumonia in Wormwood Scrubs prison, only weeks after his arrest when in full health and strength.

“Of course double pneumonia might have caught him outside prison,” commented the Statesman, “but it was inside that he died.

“Twenty-three conscientious objectors have died since the Military Service Act came into force. Seven per cent of all COs who reach prison achieve a complete physical breakdown.

“In the last seven months the authorities have had to release 90 on the grounds of health… If the progressive parties in the House of Commons were worth tuppence, and were led for tuppence…the state of affairs would be altered at once.”

British agent in Russia Bruce Lockhart had been supplying large sums of money to anti-Bolshevik forces

Well over one hundred “absolutist” COs, who endured repeated hard labour sentences for refusing war service in both military and civilian capacities, had been in jail for more than two years. One was the assistant secretary of the British Socialist Party (BSP), Ernest Cant, who was later to be active in the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) for the rest of his long life.

No Conscription Fellowship leaders continued to pay a price. General secretary Violet Tillard’s appeal in mid-July against a £100 fine or two months’ jail for not answering police questions about the printing of the NCF’s internal newsletter was dismissed and her imprisonment was soon to follow.

The NCF, incidentally, was attempting to raise money to enable its former printer — whose printing equipment had been wrecked and carted off by police in April — to replace it.

In July the Glasgow-based Socialist Labour Party’s monthly paper The Socialist was under severe threat of suppression. That month its front page featured its anti-war position with a headline question. “THE WAR: WHAT FOR?” — followed by £ symbols.

A police raid on the SLP’s press in Renfrew Street was staged on July 6, when vital parts of printing machinery and supplies of paper and ink were carted off.

The following day, as thousands of marchers arrived peacefully at Glasgow Green to call for the release of John Maclean from the savage five-year prison sentence meted out in May, the demo was treated as “illegal.” Hundreds of police waded in with raised batons to disperse the crowd.

On the Western Front the latest German offensive episode on July 15 quickly ground to a halt. Secretary of State for War Lord Milner, in War Cabinet discussion on the 31st, countered the optimism of colleagues that the war might be won in 1919: “On this he personally felt the gravest doubt. In his view the Western Front was a candle that burned all the moths that entered it.”

Meanwhile, in some factories on the Home Front, cracks were appearing in the wall of compliant support for the war.

At the Hammersmith-based Waring and Gillows aircraft factory on June 28 a lockout had taken effect. This followed the refusal of the firm to recognise its shop stewards committee as representing the workforce, its deduction from their pay of the time spent in a meeting and the dismissal from employment of their chairman, Mr Rock.

A shop floor resolution called for the cancellation of the pay deduction and for Rock’s reinstatement. All but a few of the workers declined to promise to work normally, so were locked out.

Support for the workforce was not offered by the Daily Express, which reported the dispute on July 5 with distracting disinformation: “We presume that they have listened to some subtle pacifist agitator.”

More than one of these perhaps, for speedily more than 10,000 sympathy strikers materialised from other aircraft factories in the London area. The dispute was brought to a close by an official inquiry which confirmed the dismissal of Rock (countermanding this weeks later).

During the Waring and Gillows dispute, a larger cause for industrial discontent grew as a result of a government circular quietly issued at the beginning of July to impose a form of industrial conscription, something attempted unsuccessfully earlier in the war. The circular required skilled operatives in munitions factories to be barred from moving to other firms.

While national trade union leaderships were silent, shop stewards’ movements first in Coventry on July 23 and then in Birmingham the following day made their protests loud.

Within days 20,000 men were out in Coventry and 100,000 in Birmingham. Then on the 25th a conference at Leeds sponsored by a trade union coordinating committee declared for a national strike in the industry subject to the approval of another conference on the 29th.

The vote that day retreated from action in the face of a “Work or be conscripted” ultimatum from the government. But from this ultimatum, the government itself backed off too, postponing vengeance pending an inquiry.

The threat of industrial conscription was thereby shot into the long grass.

Telling strikers they were traitors to their country was par for the course, but during this month of July, Germany-blaming-and-hating was encouraged by an anti-aliens campaign which took heart from the crazy Tory MP Pemberton Billing’s claim that “47,000” British people had been blackmailed into support for the enemy. This led before the month’s end to a tribunal’s decision to detain hundreds of elderly and innocuous Germans with war-time naturalisation certificates.

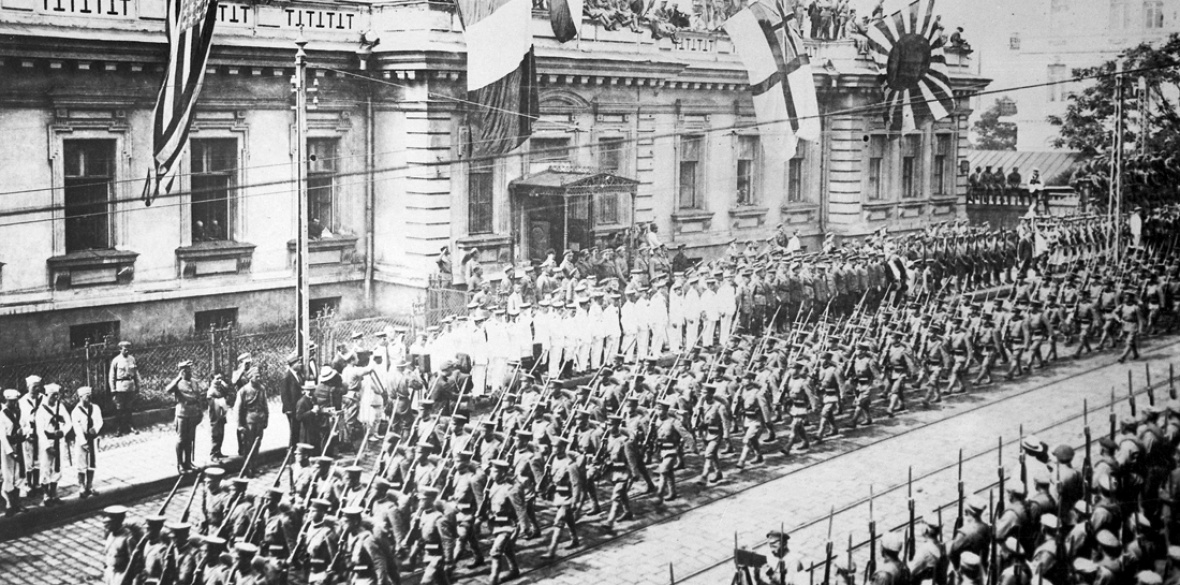

Meanwhile, approaching 2,000 British troops had landed in northern Russia at Murmansk, and some of these had advanced southwards. Joe Fineberg, Russian-born leading member of the British Socialist Party, had encountered them on his journey to St Petersburg to join the Bolsheviks.

On July 30 two British warships arrived in the Kola Inlet with a view to advancing on Archangel, the next day attacking the Bolshevik-defended Mudyuga Island before advancing up the river Dvina.

Simultaneously, another British force was close to Baku in the south while a battalion of British troops based in Hong Kong had been ordered to Vladivostok.

A significant ally was a force of Czech troops, displaced by the Revolution and occupying sections of the Trans-Siberian Railway, which had taken possession of that city before the end of June after a short battle with Bolshevik defenders.

In Ekaterinburg the deposed Tsar and family were killed on Bolshevik orders.

British agent in Russia Bruce Lockhart — a counterpart to Russian “ambassador” Maxim Litvinov — had been supplying large sums of money to anti-Bolshevik forces. His role as emissary to the Lenin government more or less at an end, he played endless “patience” card games.

“Shall the Russian Socialist Republic be crushed?” asked the BSP’s The Call mid-month.

As the intervention developed, so did the clamour in Britain to stop it.