This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE song, This Land Is Your Land, written and first sung by Woody Guthrie as a response to the song “God Bless US” — and sometimes described as an alternative national anthem — has been sung over time by everyone from Bruce Springsteen to religious choirs. Ironically the United States has far more “public” land than Britain, which has hardly any.

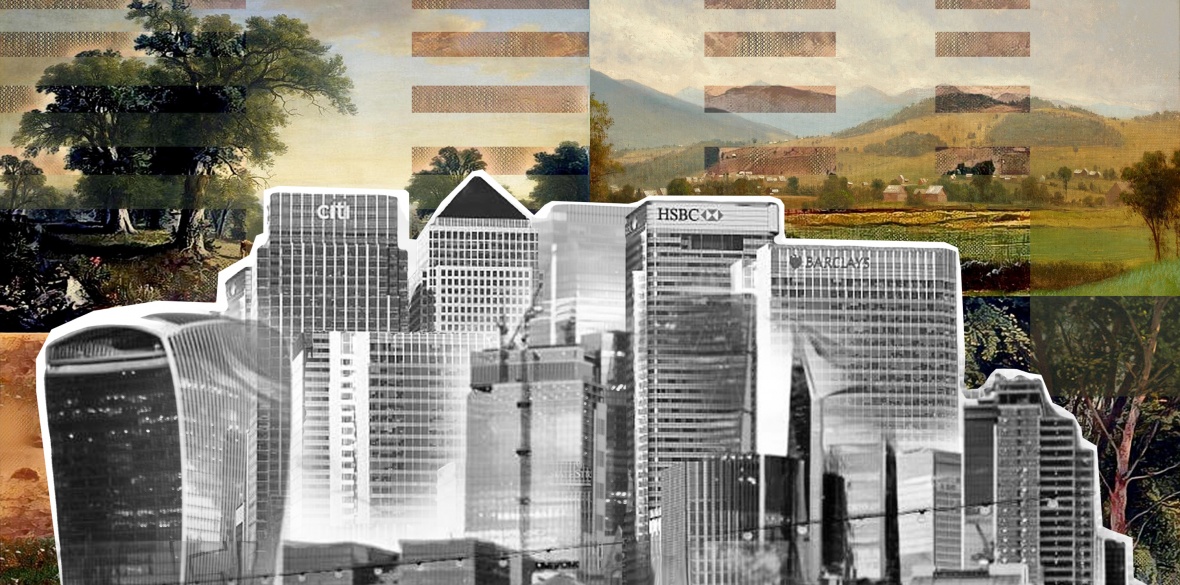

“Our” land belongs to a ruling class of landowning, industrial and (increasingly) financial, capitalists. And, like our rivers, streams, and atmosphere, it is increasingly being privatised and polluted in the interests of profit.

Marx, in a chapter of Capital entitled “The Expropriation of the Agricultural Population from the Land” describes how the English enclosure movement from the 15th to 19th century involved “the systematic theft of communal property [which] was of great assistance in swelling large farms and in ‘setting free’ the agricultural population as a proletariat for the needs of industry.” It was assisted, of course, by the profits from slavery which underlie so many of Britain’s “great estates” today.

An analysis of land ownership today reveals some of the distinctive elements of capitalism — especially British capitalism.

One of the features of British land ownership is the lack of a cadastre — of any central, complete and accessible record of who owns what. In the more than nine centuries since the Domesday Book, attempts to document ownership — the tithe maps of the 1830s, the 1873 Return of Owners of Land, the 1910-1915 Valuation maps and the 1941 National Farm Survey — have all been incomplete and the results remain confidential.

Cadastres were initiated by the French Revolution and are common throughout Europe, but Britain’s closest equivalent is the Land Registry. Founded in 1862, this remained largely dormant until 1925 when registration at the point of sale became compulsory. But information on who owned what was still strictly secret. Not even the police were allowed access without the landowners’ permission (greatly hindering any challenge to corruption and money laundering).

The Labour government’s 1974 Royal Commission on the Distribution of Income and Wealth (imagine such a commission being set up today) declared that “the paucity of comprehensive up-to-date information on land ownership is remarkable… it is difficult to carry our analysis any further.” The report of the 1979 Northfield Inquiry into the Acquisition and Occupancy of Agricultural Land contains a record of land holdings by the public sector, financial institutions and some overseas buyers — but nothing on large private landowners who owned (and still own) most of “our” land.

With Margaret Thatcher’s arrival in 1979, any remaining impetus for land reform disappeared.

A 2017 Housing White Paper announced that the Land Registry would aim to complete a comprehensive register of land ownership — and that datasets showing land owned by British and overseas companies (three million titles, covering one third of the land of England and Wales) would be publicly available. But… none of this until 2030!

Meantime although Land Registry records of title have recently been opened to public access, this is only for single properties (identified by address or postcode) and for a fee. Even if you can locate the owner of a property, you must download a PDF plan (not mappable) of the title (another fee) and there is no way of finding out what other land that individual or organisation owns. Despite the Conservative Party’s 2017 manifesto commitment to merge the Land Registry, Ordnance Survey and Valuation Office to create “the largest repository of open land data in the world” the Ordnance Survey’s jealous hold over mapping licences still represents a major obstacle to analysis.

On top of this, around 17 per cent of the land in England and Wales is unregistered: its owners (mainly wealthy families, old institutions, the Church, and the Crown) have simply inherited the land which has not been sold for decades and details remain restricted to their own private paper records — inaccessible even to Parliament!

Everything is made yet more difficult by the limited information available in relation to “Persons of Significant Control” — the ultimate owners and beneficiaries of companies registered in Britain — a fact partly responsible for the increasing trend for landed and financial capital to base itself overseas (often in offshore tax havens).

In the absence of accessible “official” data, researchers have had to use detective work. These include forced disclosures under the 2005 Freedom of Information (FOI) Act (which Tony Blair — ignoring Iraq and a host of other misdeeds — considered one of his greatest mistakes, castigating himself for being a “naive, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop”) and under the 2004 Environmental Information Regulations which are EU derived and — at least until Brexit — harder for public bodies to refuse than FOIs.

Other sources include maps deposited with HMRC by landowners to qualify for exemption from inheritance tax and capital gains in return for limited public access to their “heritage” assets. Further manifestations of landowners’ greed include their maps voluntarily deposited with the local authority to prevent any public use of their land facilitating the establishment of a new right of way.

All present a sobering analysis of the concentration of land ownership in Britain. In England, around 30 per cent of all land is owned by “aristocracy and the gentry,” some 18 per cent by corporations and 17 per cent by “oligarchs and City bankers” — together around 65 per cent.

Overall, half of Britain’s land is owned by less than 1 per cent of the population, a significant proportion of it based directly or indirectly on slavery.

Of the other half (of “our” land) somewhere between 8 per cent to 9 per cent is — or was — publicly owned. Even this is being sold off at an alarming rate. Ironically, this process in some respects goes further than Britain’s earlier enclosure movements (which in general involved denial of use and access but no change of title).

Following the nationalisation of key utilities immediately after the second world war, re-privatisation began early — including the Beeching cuts and sale of railway land that could now be critical for a programme of low-carbon public transport. Many of the public enterprises sold off subsequently — electricity, coal, and most importantly, water — were themselves major landowners.

Yet even these large landholdings account for less than one-fifth of the land that is still being privatised. Thousands of small privatisations from nurses’ homes to school playing fields sold off by health and local education authorities are even more significant. Cuts in local authority funding since the Tories came to power in 2010 have forced local authorities to sell around £1.2 billion in assets every year in an attempt to balance budgets.

This is in addition to “right to buy” sales. In 1979 there were 6.5 million council homes in England; today there are just 2.2 million while some 4.4 million households rent from private landlords — twice as many as 15 years ago and 40 per cent of which consist of former right-to-buy properties. “Worth” around £40bn, council house sales are sometimes held to be the biggest privatisation so far.

Much of its value — whether in high-rise flats or low-rise semis — is the land on which it sits. Land today represents on average around 70 per cent of the sale price of residential housing. But housing represents only a small proportion of the land that has been sold off. Homeowners together own only around 5 per cent of Britain’s land, much of it mortgaged.

The focus of opposition to privatisation is, understandably, on publicly owned services —health, education, utilities, transport, security — and enterprises but the biggest and most significant privatisation by far is land. As Mark Twain said: “They’re not making it any more.” In 1979 around 20 per cent of Britain’s land surface was in public hands. Since Thatcher launched the big sell-off, the state has “sold,” often at knockdown prices, over half of this — some 2 million hectares or 10 per cent of the entire British landmass.

Privatisation — whether of land or other capital — is ultimately about class power. Commercial developers have been major beneficiaries of privatisation of public land and property and they are also major donors to the Conservative Party. The party in return has been the instigator of and driving force behind the process — and both Houses of Parliament contain disproportionately high numbers of landowners.

At the same time, widespread disillusion with the Tories and the collapse of any kind of vision of a progressive future on the part of Labour makes it more important than ever to awaken the sense of outrage everyone should feel that so much of what was “ours” has been taken away and to re-ignite a vision of what this land — our land — could be. We’ll look at this further in the next Full Marx column.

The Marx Memorial Library's rich autumn programme continues on Thursday November 16 with an online and on-site lecture on the famous Marx House Fresco. On Saturday 18 there’s an online symposium Popular Front: Learning the Lessons of Resistance to Fascism; on Wednesday 29, an evening of document displays will include a guided walk on radical Clerkenwell in collaboration with London Metropolitan Archives, and on Thursday 30 there's an onsite and online panel on the lessons of the 2022-23 trade union offensive. The programme continues on December 7 with an onsite film screening of The Brigaders Return to mark the 85th anniversary of the return from Spain of the British International Brigade. Details of these and much, much more on MML's website www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk.