This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

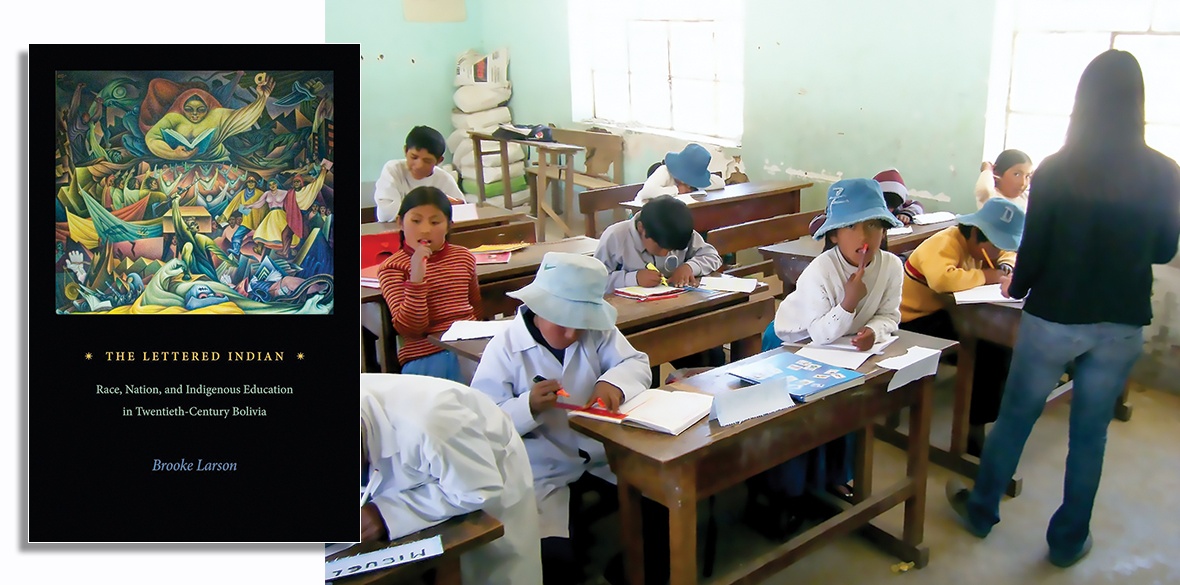

The Lettered Indian: Race, Nation, and Indigenous Education in Twentieth-Century Bolivia

by Brooke Larson

Duke University Press, £25.99

THE US-backed right-wing coup against Evo Morales in Bolivia in 2019 and the violent turmoil fanned by the white elite that both predated and followed it demonstrated above all else that, for this country’s Indigenous majority, there is much unfinished business.

Jeanine Anez, the usurper who, with the support of the military, all but installed herself — now jailed for her political crimes and facing genocide charges — epitomises the racism at the heart of the imperial legacy, wont as she is to describe Bolivia’s Indigenous majority as “savages.”

No matter where you stand on mistakes made by Morales’s Movement for Socialism (MAS), to a large extent the coup represented a white, racist reaction to the prospect of the country’s first Indigenous president of Bolivia remaining in power after 13 years.

As Mark Weisbrot has noted, the coup was led by a white and “mestizo” (mixed Spanish and Indigenous) elite with a history of racism, seeking to recapture the monopoly on power they had enjoyed for centuries before Morales was first elected in 2005. All the victims of the two largest massacres committed by state security forces at counter-protests following the coup were Indigenous.

The return of MAS under a new president, Luis Arce, demonstrates, however, the direction of history in this country.

MAS governments are known above all else for the advances made by the Indigenous population — the largest of any country in the Americas — by rolling back historic oppression, inequality and cultural erasure. Morales reduced poverty by 42 per cent and extreme poverty by 60 per cent, disproportionately benefiting Indigenous Bolivians.

Moreover, the return of the MAS also demonstrates that the white elite with their backers in Washington are now fighting a rearguard action: Bolivia under the MAS appears to be winning its long struggle to decolonise.

Indeed, the announcement by Morales of his candidacy for the 2025 presidential election might suggest that he has concluded, as have others, that the 2019 coup was in fact the last gasp of a drowning man.

At one level, reading Brooke Larson’s book, that is unsurprising. The author summarises the remarkable and inspiring advances that have been made over four generations towards arguably the greatest prize of all in Indigenous emancipation — the establishment of an Indigenous historiography and cultural enfranchisement through education.

While the extent to which these remain works in progress remains open to analysis, Larson’s eloquent study of Indigenous education in Bolivia lays bare with triumphant clarity the inevitable destination: the reclamation of a heritage and identities from the iron grip of tight Euro-American imperial narratives.

The Lettered Indian examines the politics of education in the Bolivian Andes from the early 1900s to the 1970s, at the very heart of which was “the rural Indian school as a contested site and symbol of knowledge, power, and identity during the political and cultural formation of neocolonial modernity.”

Rural schooling, the author argues, represented an intercultural battleground over wider social issues of race, nation and education in the making of postcolonial Bolivia.

As such, this fascinating study provides a key insight into the discourse and practice of race and indigeneity in the nation-building projects of elites and those they dominate, behind which Indigenous Bolivians themselves sought to wrest the agenda into their own hands.

Larson traces the evolution of attitudes and approaches to educating “the Indian” from high-handed schooling to change this subject’s outward behaviour and inner character by enlightened men of letters who were (unwitting?) agents of anti-Indigenous racism.

Cosmopolitan ideas shaped by racial determinism ranging from social Darwinism to Eurocentric notions of Anglo-Saxon racial superiority created an entire genre of “tutelary race thinking” shaping ideas in the Liberal state that competed to influence educational policy.

Yet Indigenous school activism and hunger for literacy in the Aymara hinterland were ever-present, and Andean political interests themselves began to transform the civilisers’ ideal of the “educated Indian” into a “lettered warrior,” a long and halting process influenced by pedagogical debates, interventions and the broader, inescapable dynamics of political conflict in a racially divided and turbulent polity.

A key development in this long and winding path came with the remarkable communitarian school project in the Altiplano in the 1930s that would have an enduring impact on subsequent developments, the Warisata “escuela-ayllu” near La Paz that Larson argues “marked a fundamental turning point in Bolivia’s tortured history of Indian/state relations.”

A unique and iconic experiment in communal restitution, self-governance and community-based schooling by criollo educators and Aymara peasant leaders that captured global attention, the success of this 10-year initiative was such that it eventually was considered threatening by the conservative elite as a seed of Indian redemption.

As a result, and with tragic inevitability, growing state aggression to the ayllu-school movement crystallised into violence and repression.

As Larson writes: “Once again, traumatic events lay bare the underlying cultural violence of internal colonialism, rooted in the oligarchy’s denial and fear of the educated Indian.”

Fast-forward past the 1952 revolution under the MNR — a period of political transformation but also integrative cultural nationalism that transformed the rural school above all into an instrument of state-building — and we reach the slow revindication of Warisata in the late 1970s, a portal through which an early generation of Aymara scholars began to introduce a decolonial historiography. The 1980s and what happens thereafter, while not the main focus of this book, is an inspiring period of progress.

Larson writes: “the Aymara interpretive rediscovery of Warisata’s original significance marked another epistemic turning point in the decolonisation of Bolivia’s history/historiography of education.”

Fast-forward again to public education initiatives under Morales — not least the creation in 2008 of UNIBOL, the Indigenous University of Bolivia — and the destination of this process, and the reason it provokes such hostility in the elite, comes into clear focus.

It is no coincidence that the Aymara UNIBOL was founded in Warisata, with Quechua and Guarani branches in Chapare and Chaco, and that the stated, official ethos of these institutions is the “decolonisation” of education, a truly outstanding achievement.

As Larson writes: “Whereas the ‘lettered Indian’ used to be viewed by the oligarchy as a danger to the neocolonial order, Bolivia’s educated Indigenous people, armed with strategic knowledge, power, and governing skills, are now shaping the content of their own social subjectivities and political destinies.”

This article first appeared in The Latin American Review of Books, latamrob.substack.com