This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

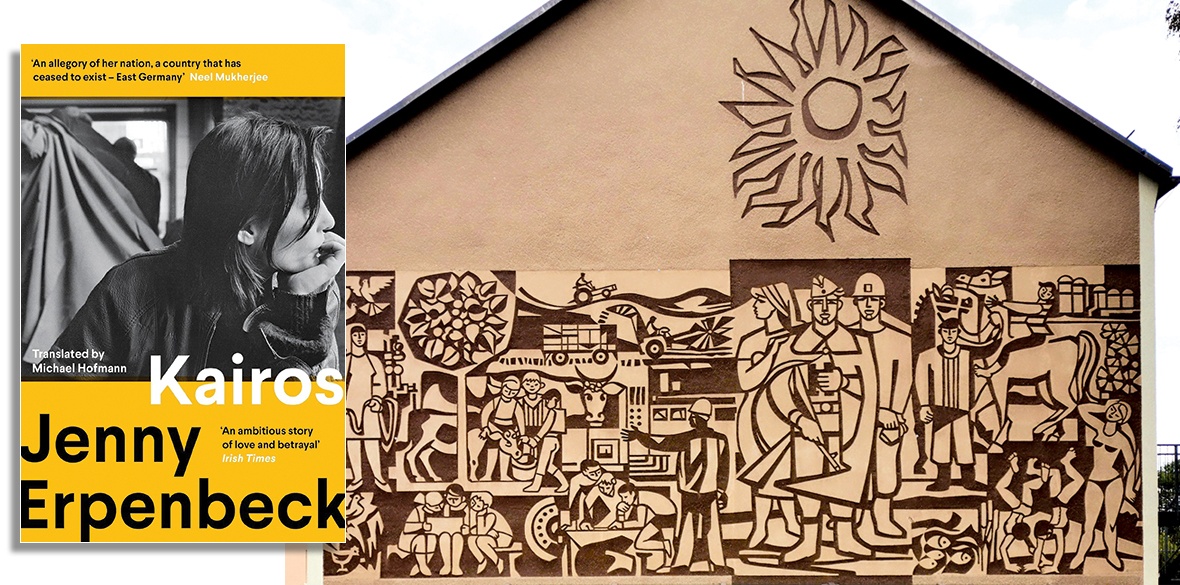

Kairos

Jenny Erpenbeck, Granta, £16.99

TO read Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel is an eye-opener for those who wish to find out more about life in East Germany (GDR) in the final years of its existence and beyond.

Unprejudiced readers will discover a highly cultured society, a place where everybody has free access to education, training and a job. For readers who remember the GDR, the book includes a wealth of references to a dizzying array of fine artists who lived there or those who were part of the anti-fascist tradition.

The novel spans the years 1986 to 1992, with the final section depicting the dissolution of the state, mass redundancies, unemployment, unaffordable rents and cultural hollowness.

Jenny Erpenbeck builds her story around the narrative of a relationship between the 19-year-old Katharina, and a 53-year-old writer and radio broadcaster, Hans.

Her male protagonist is a very well-read author who has had frequent affairs. In several respects, his childhood in Nazi Germany has cast shadows on his adulthood. This includes Hans’s need to blame and punish others for perceived “betrayal,” his latent violence, his need to feel superior and be controlling.

Hans’s trajectory from a Hitler Youth to one who now unquestioningly follows a different flag is representative for his generation, while Katharina is more characteristic of her own age group, born into the GDR and naive to Hans’s manipulation.

The relationship soon develops into one of psychological control with masochistic overtones, making the young woman feel unworthy and dependent. Katharina only realises late on that the relationship is destroying her, because she considers herself emancipated.

As the story progresses to the dissolution of the GDR and its annexation by West Germany, Erpenbeck incorporates detailed references and documents regarding the aspirations of many for socialism.

These desires are integral to the intricate historical backdrop of the book “Socialism must find its own democratic form, but not lose itself. That’s what it says in a paper that Katharina’s mother and Ralph put their names to and showed her over their drinks. In its quest for a durable form of social organization, humanity needs alternatives to Western consumer society. Welfare must not be at the expense of poor countries.”

However, the swift emergence of capitalist, semi-colonialist reality soon dashes any hopes for a more democratic socialist system: “Already the eastern districts have started to smell different, clean and nicely scented West Berliners are inspecting streets that are named for the working-class president Wilhelm Pieck, the Bulgarian Communist leader Dimitrov, the socialist prime minister Otto Grotewohl — all names that mean nothing to them. They will use the word ‘grey’ to describe the section of the city that has no neon advertisements.”

In the book’s concluding section, the atmosphere during the fall of the Berlin Wall is vividly recreated.

About the wholesale redundancy of GDR employees she writes in Kairos, recreating the exact circumstances: “Early in December 1991, Hans is dismissed, along with all the other 13,000 employees of the broadcasting services of a state that no longer exists. And because the waiting rooms and corridors of the Berlin labour exchange are too small to take the 3,000 who are suddenly out of work in the capital alone, the labour exchange sets up for three days in the great broadcasting hall of the East Berlin Broadcasting Service and gives a guest performance there.”

On the full-scale destruction of a literature, reminiscent of the Nazi book burning, the novel recalls: “Books Worth 240,000 Marks in the Trash: The Karl Marx bookstore on Wednesday cleared out its unsold stock. The manager says he needs warehouse space for new titles. Even quality literature had proved unsalable. For many tons of books, the trash heap is the final destination.”

Why does the author connect the story of this affair with the collapse of socialism?

Erpenbeck explains: “Betrayal and lying are at the center of my work. Kairos is a slow process of how something meant as a kind of truth actually transforms into a relationship with lying at its centre. As it was in the political history of the GDR. Ideas were received enthusiastically in the beginning, a new start after fascist times. Slowly, a certain vocabulary was forbidden, a certain exchange of opinions not allowed. People started to deliver ready-made sentences.

“We are coming to a similar time now, because there are certain sentences that you are supposed to deliver and others sentences that you are not supposed to deliver anymore.”

In contrast to the flood of so-called memoirs of the East, often written by people who have no knowledge or memory of this epoch, Erpenbeck's narrative diverges from the prevalent Western discourse. Through her portrayal of ordinary lives, she poignantly illustrates the losses endured after 1990.

Erpenbeck provides an insider’s perspective. Her characters are believable and lead fulfilling lives. East German readers appreciate Erpenbeck's portrayal of their lives and achievements, which resonates with their own experiences and preserves their dignity.

Erpenbeck is the first German writer to win the International Booker Prize.