This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE scale of the deepening social crisis is beginning to dawn across Europe. The 80 per cent increase in household energy costs in Britain may be exceptionally big.

But the crisis is far from unique to Britain. Nor is the kind of excuse that Boris Johnson trotted out on yet another visit to Ukraine this week: that ordinary households in Britain have to endure soaring prices and falling living standards as part of “standing up to Vladimir Putin.”

French President Emmanuel Macron said similar on Wednesday as he prepared his government for massive public anger and bitter opposition to his programme of attacks on pensions and benefits.

He cited not only the Ukraine war — which one Nato state after another has given as reason to increase arms spending — but a range of issues from climate change to precarious global supply chains that amount to a systemic crisis.

“I believe that we are in the process of living through a tipping point or great upheaval. Firstly because we are living through … what could seem like the end of abundance,” he said.

He touches on a truth, though as union leaders and politicians of the left pointed out, there hasn’t been much in the way of abundance for working-class France.

Macron’s emergency measure to limit energy price rises to 4 per cent has had a better reception in Britain, where it stands in sharp contrast to the Tory government’s “let them freeze” approach, than it has had in France.

It expires at the end of this year. Government spokesman Olivier Veran said that the cap on energy prices could not continue “indefinitely.”

In a typically haughty announcement that again shows there is more that unites Macron and Johnson than divides them, he has called on French citizens to “take responsibility” and make sure they do not leave lights on. The problem is going to be turning them on, not forgetting to switch them off.

It is the same story in country after country. The German coalition government, which includes the Greens, is also calling on the population to make sacrifices while ramping up its military budget and allocating a special €100 billion arms fund. Its status will be written into a revised German constitution.

What is taking place is beyond a “temporary” cost-of-living crisis. We are seeing epochal changes and shocks which will likely mean big upheavals and social clashes of the kind that followed the 2008 crisis.

Then, a combination of food price inflation and global financial crisis weakened all sorts of political systems and mechanisms of social stability.

It led to revolutionary upsurges in Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere, and to mass strikes and the occupation of public squares in Spain and Greece.

The crisis threatened to prise the eurozone apart and led to sharp political polarisation. Greece saw the rise of the radical left and of the neonazis.

The imposition of austerity — with particular brutality on the European south — was justified as the only way to prevent default by states that had now taken on the debts of the private banking system.

This week the spectre of such defaults returned. Hedge fund speculators have amassed the biggest bets against Italy’s debt mountain since 2008.

The country is especially vulnerable to disruption of gas supplies from Russia. That has not stopped the outgoing prime minister Mario Draghi from enthusiastically joining the guns not butter club and talking up the sacrifices Europe and Italy at war must make.

The fall of his government means elections next month. The far-right Brothers of Italy are likely to come first. They and other parties of the right have declared their commitment to Italy’s eurozone membership but have also indicated that they may review Italy’s €200bn EU-funded recovery plan.

That ties eurozone funding to further liberalisation of the Italian economy in the manner of the bailouts of Greece and others in the last decade.

This is at just the moment when economic interventions are required that fly in the face of the old neoliberal nostrums.

Draghi, who was a pivotal figure in enforcing those austerity memorandums, has warned whoever is his successor that they must stick by the EU’s rules.

As he has governed so also at the moment of his leaving Draghi has been the EU’s unelected prime minister in Italy more than an Italian prime minister representing his country.

Interventions by the European Central Bank and other institutions are setting the stage for confrontation if a new government tries to loosen the financial straitjacket.

Unlike with the Syriza-led government in Greece in 2015, this confrontation would be with a government of the hard and far right. Its racist anti-migration policies are shared by Brussels.

A standoff between Brussels and Rome in which the far right and not the left and working-class movement can claim to be defending popular sovereignty and living standards threatens a very dangerous radicalisation of fascistic forces. Not only in Italy.

Posed today are more than the immediate issues of wages, prices and working-class organisation. We can already see how fundamental questions are raised over the whole direction of society, who governs and which class holds power and leadership of the country.

The Citizens Advice in Britain estimates that the next price cap rise in January will lift the proportion of households unable to pay their bills from 25 to 33 per cent. Half of them will be “a new group of people who would otherwise be more financially stable.”

Another report this week found that high street and other small businesses are at severe risk from the quadrupling of energy costs.

It is very hard to slash energy use in a hairdresser’s salon. These are the kinds of places that are hit quickly and hard when people cut “discretionary spending.”

There are 5.5 million people who are self-employed or in small, family businesses. Unlike the big corporations whose often oligopoly position means they can pass on price increases, these businesses cannot in the same way. The greengrocer and hill farmer get squeezed. The supermarket chains make record profits.

This happened on a vast scale in Greece a decade ago. It was not only the working class that suddenly found itself falling through the floor. It was self-employed professionals, independent pharmacists, the small guest-house owner (tourism is the country’s major industry) and all sorts of people who had felt securely above the precariously employed.

From borrowing against rising house values home owners defaulted on their mortgages. Britain has not experienced such a social collapse for a very long time. It is about to.

The experiences of countries such as Greece a decade ago are set to have renewed relevance. Trade union action was critical not only to blunting the impact of the crisis at workplace and industry level.

A succession of one-day national strikes — general strikes across the public and private-sector union federations — posed the political question of an alternative to the austerity and the system that produced it.

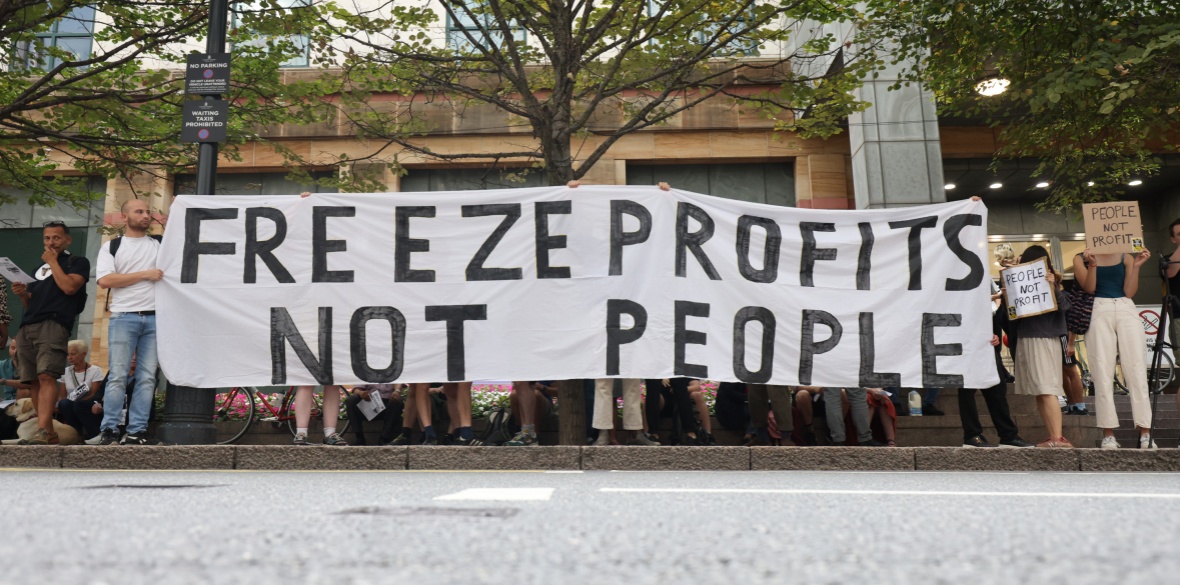

Already in Britain responding to the employers’ propaganda about wage rises leading to inflation means a national discussion about profits, redistribution and price controls that has not happened on this scale for nearly half a century.

Greeks were told that repudiating unpayable debt would mean the collapse of the country’s financial system. Answering that argument meant raising nationalisation of the banks and thus throwing the burden of economic restructuring onto big business.

Developing a crisis programme from the left was an integral part of sustaining the revolt in Greece 10 years ago. It was part of winning those who were not employed in workplaces or members of unions to the leadership of the working-class movement and away from the nationalist and far-right forces who sought to turn mass despair against the left and unions.

The occupation of the squares in Greece in 2011 sharply focused this political contestation. It was thanks to a unified intervention by the bulk of the left that nationalist and anti-left sentiments — and activists — were marginalised rather than the left finding itself isolated.

Similarly in France more recently where left and labour movement forces contended with the far right in the yellow vests eruption.

In national political terms it meant Jean-Luc Melenchon vying with Marine Le Pen in the first round of the French presidential election — and coming close.

That the Syriza government in Greece failed in 2015 demands detailed critical reflection. The same is true of the fate of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolts of 2011.

That should not obscure the vital lessons of how at key points the radical left and the working-class movement were able to pose an alternative path for the whole society.

The exceptional level of public support for many strikes today — 63 per cent for the postal workers — indicates people looking to the trade union and social movements even if they are not yet of them.

That can change. In both directions. So there is a great urgency this autumn.

To build and draw together all the campaigns and struggles. To unite the left on that basis now to voice a radical alternative way out of this crisis that will shock millions as it fully hits.

To provide a focus for many millions — and to debate seriously so as to ensure that we do better than last time.