This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE mainstream political culture — from the media to politicians to academia — often has a hard time recognising the decisive role of grassroots activism and protest in securing political change.

For example, last month the Guardian reported on the latest British Social Attitudes survey, noting: “From attitudes to gay sex and single parenting to views on abortion and the role of women in the home, Britain has evolved into a dramatically more liberal-minded country over the past four decades.”

According to the liberal newspaper, the study suggests “the evolution of liberal public attitudes ... have been driven by profound social changes such as more people going to university, more women going out to work and the decline in marriage and organised religion.”

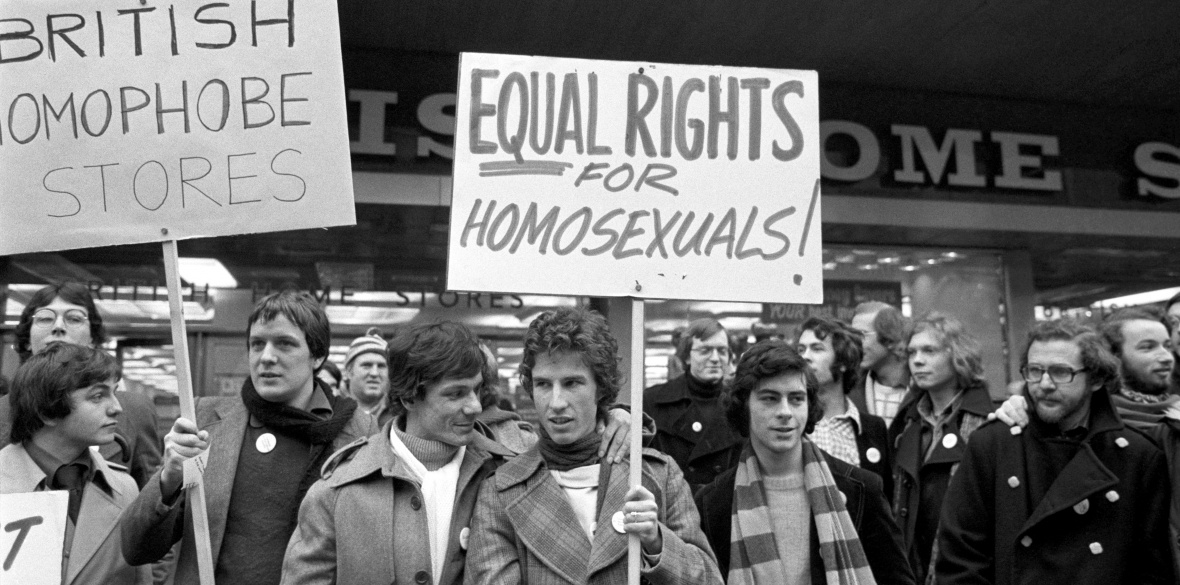

Missing is any reference to the decades of essential work done by the feminist, gay and left-wing activists, with groups like the Women’s Liberation Movement, Stonewall, the Gay Liberation Front and Outrage dealing with violence, threats and abuse in their struggle to win equal rights, changes in the law and shift public opinion.

The tendency to conflate “politics” with “Westminster” is a common way in which grassroots action gets sidelined.

Writing for the Hansard Society blog in August, Dr James Strong, a senior lecturer in British Politics and Foreign Policy at Queen Mary University of London, highlighted four factors which determine whether Parliament gets to decide on military action.

These are: the Prime Minister’s position, the balance of power between the political parties, what prior experience MPs have had of voting for war, and the nature of the proposed military operation. Missing again is any reference to the role of social movements or public opinion, which the historical record reveals as being crucial in determining the shift in parliamentary norms on matters of war.

As Strong’s research shows, the constitutional convention that Parliament be given a vote in advance of military action was set in March 2003, when Labour Party prime minister Tony Blair held, and won, a parliamentary vote to invade Iraq.

However, as Milan Rai, the editor of Peace News newspaper has explained: “Tony Blair did not want to have a vote in Parliament on whether or not to go to war with Iraq. It was the anti-war movement, both inside and outside the Labour Party, that forced Blair into holding the vote.”

Indeed, Strong himself helps to corroborate this reality in a 2014 article, noting that “until after January 2003” Blair maintained “he would decide and then Parliament would discuss, but not vote on, war with Iraq.” The problem for the prime minister, as Andrew Rawnsley set out in his 2010 book The End Of The Party: The Rise and Fall of New Labour, was that the impending war “was already hugely contentious.”

The growing anti-war movement held huge rallies in London in September 2002 and February 2003, engendering rising discontent within the Labour Party itself. In January 2003 the Guardian noted ICM polling was showing support for the war had slumped to its lowest level since it started tracking opinion on the question in summer 2002. According to Rawnsley, Jack Straw, the foreign secretary, told Blair if MPs were denied a proper vote “people will go berserk.”

The flagship BBC news programmes also seem institutionally prone to framing politics as whatever happens in SW1. “Since we ... see ourselves as public policy journalists then necessarily we look at what is happening in public policy i.e. politicians and officials” rather than “those who were not in a position to make decisions, like the anti-war movement,” Kevin Marsh, the editor of the BBC Today programme in 2003, told me when I interviewed him about the run-up to the Iraq war.

Another reason why what happens in the streets is disregarded is because politicians sometimes have the audacity to claim responsibility for positive changes that were in fact fought for by grassroots campaigns — often in the face of elite opposition.

Appearing on BBC Radio 4’s Any Questions in the summer, Chris Philp, the Minister of State for Crime, Policing and Fire, did exactly this: “10 years ago, or 15 years ago, a huge proportion of our domestic electricity was generated by coal-fired power stations, which are unbelievably polluting in terms of CO2,” he noted, before bragging, “We now have virtually zero electricity generation in the UK from coal-fired power stations.”

In contrast, when no coal was used to generate electricity in Britain for a week in May 2019, environmental campaigner Joss Garman tweeted: “It’s not an accident. A decade of activism and organising at all levels made it happen.”

The first Camp for Climate Action rocked up at Drax coal-fired power station in summer 2006, Greenpeace campaigners occupied Kingsnorth coal-fired power station in October 2007, and activists “hijacked” a coal train in June 2008.

The same month, the Conservatives did propose a policy of only supporting new coal-fired power stations if they incorporated carbon capture and storage (which was, and still is, unlikely to happen). But note the circumstances and date — it was when the Tories were in opposition, keen to rebrand, and in the wake of the civil society-led campaign. And, surprise surprise, when they got the keys to Downing Street they weakened some of their proposals.

“The recession is Eon’s stated reason for ... pulling the plug,” an editorial in the Guardian noted when the energy company withdrew their plan to build a new coal-fired power station at Kingsnorth in October 2009. “The awkward squad of activists who have variously agitated, camped and campaigned over two years will take some persuading that this account represents the whole truth.”

Ignoring the role of activism in political and social change is problematic for a number of reasons.

As the examples above show, campaigning often plays a key role, so ignoring this means people will have trouble understanding how the world works. Second, important figures and organisations will not receive the recognition and respect they deserve. And third, it means the general public will find it more difficult to comprehend its own agency and power to influence government policy.

This is especially concerning when it comes to the climate crisis because, to stand any chance of a liveable world in the future, we desperately need to build huge social movements that can exert an unprecedented level of pressure on governments to force them to implement policies that rapidly reduce carbon emissions. And this needs to happen as soon as humanly possible.

The British government recently approving the development of the Rosebank oil field — which could lead to the equivalent emissions of running 56 coal-fired power plants for a year — has significantly raised the already high stakes.

The good news is that in December 2021 the Stop Cambo campaign won a huge victory, forcing Shell into announcing it was pulling out of the controversial oil field project off the Shetland Islands. The role of protest was confirmed by media coverage at the time.

“Shell says the economic case for investing in this project just isn’t strong enough. There is more at play here than just economics and making money,” Paul McNamara reported on Channel 4 News. “Senior City financiers have told us the blowback they would get from shareholders, from pension funders, from the press, from the public, mean that pumping yet more money into firms with so-called dirty investments often just isn’t worth the hassle now. With Cambo oilfield, there is a reputational liability for Shell, and ultimately it is one they’ve decided to walk away from.”

We know too that Equinor, the oil and gas giant which is set to develop Rosebank, has U-turned on other projects. Earlier this year it paused its development of Bay du Nord in Newfoundland, Canada, and in 2020 it abandoned plans to drill for oil in the Great Australian Bight.

While Equinor, which is majority-owned by the Norwegian government, said the latter project did not make commercial sense, the Guardian described it as “a significant win for environment groups and other opponents of the project, including indigenous elders and local councils.”

Of course, the very existence of a grassroots campaign doesn’t guarantee success. Far from it. But, to quote the playwright Bertolt Brecht: “Those who struggle may fail, but those who do not struggle have already failed.”

Follow Ian on X @IanJSinclair.