This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

LAST week, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Australian counterpart Scott Morrison agreed to deepen military co-operation.

Coming shortly after Australia’s new military agreements with India, another US ally, this was bound to rattle China.

Japan has shown mixed feelings towards the growing confrontation between Washington and Beijing.

China is a major trading partner and the two countries have co-operated over Covid-19, sharing expertise and medical supplies.

Relations with the US military, which has 50,000 troops stationed in Japan, are tense and Defence Minister Taro Kono angered the Pentagon last month by cancelling plans to build Aegis Ashore US-designed missile defence sites, though under US pressure Japan is now reconsidering.

But for Abe, deteriorating relations have their uses. His mission in office has been the revocation of Article 9 of Japan’s constitution, which outlaws war as a means of resolving international disputes.

Partly as a legacy of the horror of the atom bombs, Japan has perhaps the strongest peace movement on Earth, and resistance to the project means Abe failed to meet his pledge to see the article amended by the beginning of this year.

But he insisted in March there was “no wavering in my resolve to amend the constitution.”

And China’s doubts about his intentions are justified by his entire attitude to the events of 75 years ago — events in which his grandfather played a significant role.

This spring, as we celebrated 75 years since the defeat of fascism, the Morning Star warned against the revisionist tendency to belittle the role of the Soviet Union in liberating Europe or even present it as an aggressor like Nazi Germany.

This revisionism is obviously an insult to the 27 million Soviet war dead, but it also has a malign modern purpose in rehabilitating Nazi collaborators, legitimising far-right racist movements across eastern Europe and heightening tensions with Russia, on whose borders Nato armies engage in provocative war games.

The war didn’t end with Germany’s surrender in May — it continued in the Far East for another three months, with Japan surrendering on August 15.

That surrender took place in the shadow of the terrible war crimes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when the United States dropped atom bombs on those cities and killed hundreds of thousands of civilians.

VJ Day is less marked than VE Day in Britain, and Japan’s wartime record is not as well known as Germany’s in the West.

But its place in the US-led alliance now whipping up a new cold war against China gives it a renewed relevance.

For the West, Japan’s invasion of China is ancient history, particularly since the roles of the two countries in relation to our governments is now reversed: Japan is seen as an ally, China as an adversary.

But just as with Ukraine’s glorification of Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera, we can draw a direct line from the war criminals of the 1940s to the modern Japanese right.

Without understanding this it is difficult to grasp what Japan’s role in the anti-Beijing alliance signifies to people in China.

China’s human losses in the second world war were greater than those of any country except the Soviet Union, with estimates placing the number of dead at between 20 and 25 million.

Like the Nazis, the imperial Japanese armies deliberately killed civilians on a massive scale.

They had a particular interest in germ warfare, bombing China with fleas infected with bubonic plague, for example.

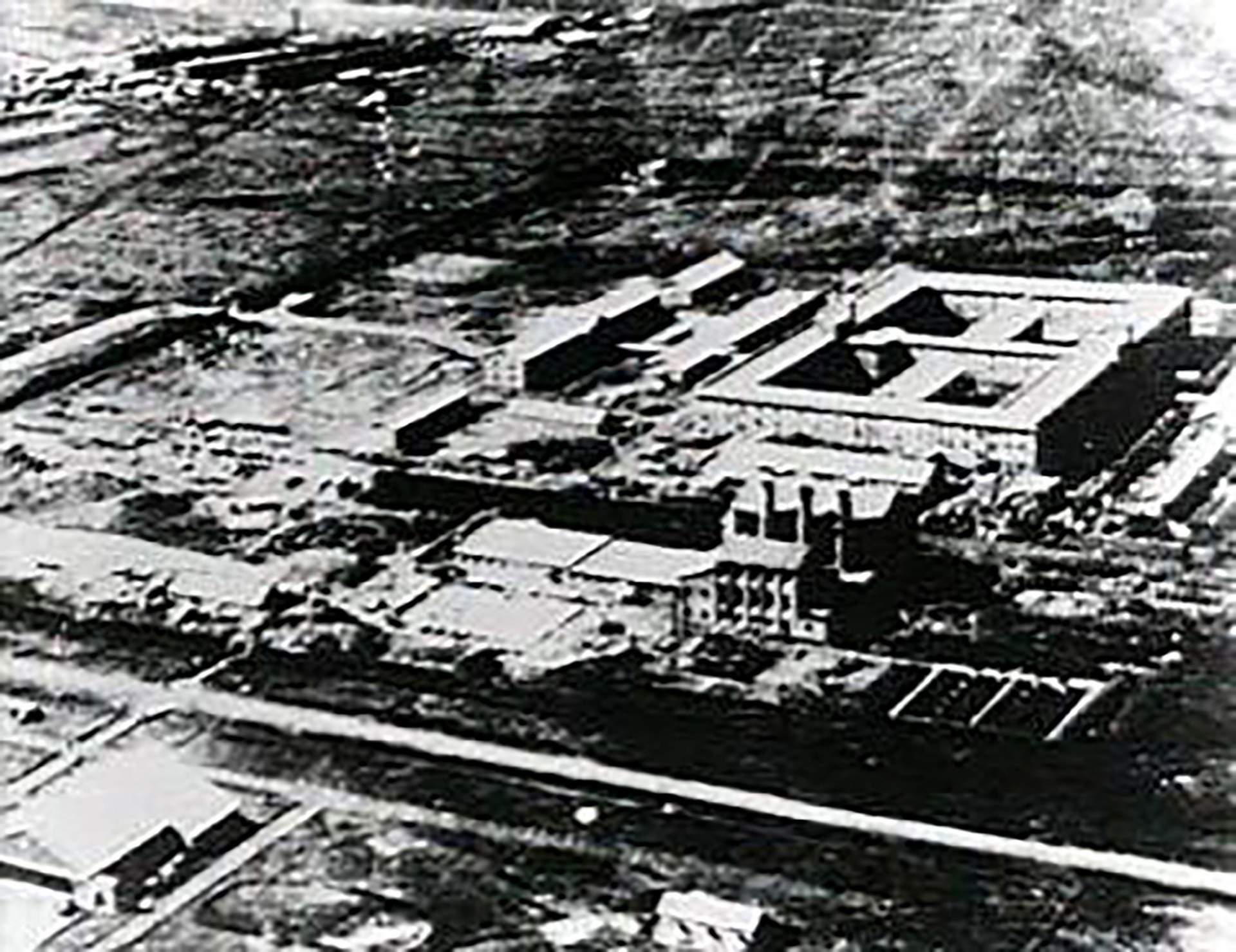

Grotesque medical experiments on humans were carried out at Unit 731, a research station in Manchukuo, as the Japanese puppet state established in Manchuria was known.

Chinese civilians were rounded up from the surrounding area for use in these experiments.

These included being infected with lethal diseases, often followed by live vivisection of men, women, children and infants to remove internal organs to study the development of disease.

Weapons such as flamethrowers and grenades were tested on live subjects. Other experiments looked at the effects on humans of burns, pressure, starvation, dehydration, electrocution and various chemical weapons.

The unit bred fleas for use in bubonic plague bombings, and organised field trips with projects such as the infection of Nanjing’s water supply with typhoid.

Accounts from Japanese soldiers stationed at Unit 731 make it clear that the rape of female inmates — including those already dying from the results of horrific experiments — was part of the daily routine of the camp.

There can have been few such nightmarish prisons in human history.

After the second world war, the United States spirited away some leading Nazis in exercises like Operation Paperclip.

It wanted their scientists, or it saw their value as anti-communists in the cold war: for this reason Nazi collaborators from Ukraine were rescued from prisoner-of-war camps and taken to the US to found the Captive Nations Committee and later the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

West German intelligence and, after rearmament, armed forces were replete with former Nazi officials.

Nonetheless, many of the most notorious Nazi war criminals were publicly tried at Nuremberg, their crimes detailed for posterity in public.

Though the Soviets, who liberated Manchuria in 1945, were able to try a limited number of Japanese war criminals at Khabarovsk, the leading figures in the Japanese war machine were not held to account in the same way and many maintained their power and influence in post-war Japan.

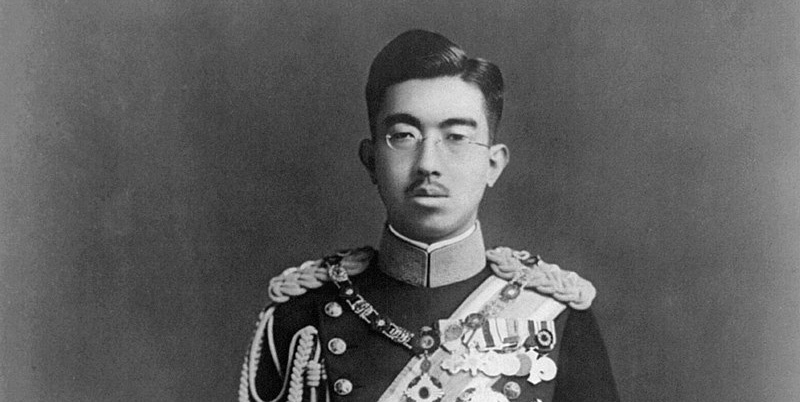

The US determination to turn Japan into an anti-communist bulwark in east Asia involved keeping the Emperor Hirohito on the throne, presenting him as a constitutional monarch not directly involved in the horrific behaviour of his armies.

Actually Hirohito wielded supreme political authority in wartime Japan. He personally issued the decree that established Unit 731.

The unit’s director Shiro Ishii also escaped justice, being granted immunity by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in return for passing details of his experiments to the United States for use in its own biological warfare research.

Another war criminal who was never held to account was Nobusuke Kishi, who ruled Manchukuo in the 1930s.

Unit 731 was on his territory, but that was not the only reason he earned the nickname “the Devil of Showa” (Showa being the reign-name of Emperor Hirohito).

Like many Japanese commanders, Kishi was an unapologetic racist, comparing the Chinese to dogs.

An estimated 10 million Chinese people were forced into slave labour in Manchukuo under his rule, many rounded up in other parts of China after Japan’s all-out invasion began in 1937 and transported to work in the mines and factories of the region Japan intended to be the industrial base of its “pan-Asian” empire.

Conditions were brutal; in the Futenma coalmine worked by 40,000 slave labourers, more than half the workforce had to be press-ganged annually because of the number who died.

Kishi was arrested at the end of the war, and held for three years as a Class-A war criminal in the Sugamo prison.

But he was never brought to trial, being released in 1948 as US officials decided he would be a useful right-wing influence in Japanese politics.

He played a major role in the merger of Japan’s Liberal and Democratic parties, establishing the single-party dominance that would last decades, and was prime minister of the country from 1957-60, though his stated ambition — to abolish Article 9 of the constitution and rearm — was never fulfilled.

Kishi’s grandson is Shinzo Abe. Abe cannot of course help that. It cannot be said however that he has done much to distance himself from his grandfather’s legacy.

Aside from their shared obsession with abolishing the Peace Constitution, Abe’s nationalist stunts are calculated references to Japan’s wartime record: being photographed posing in a military jet emblazoned with the number “731” in 2013 was hardly a coincidence.

He has questioned the idea that Japan’s behaviour during the second world war — that is, the military invasion of China and much of south-east Asia — can be fairly described as “aggression” and ordered the rewriting of school textbooks to remove references to the “comfort women” (mainly Korean women forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese army), sparking repeated confrontations with South Korea.

The United Nations marks its 75th anniversary this September 21, and secretary-general Antonio Guterres has referred to “clashes” over how that is to be marked.

He did not elaborate, but the UN was the child of the Allied victory over fascism.

China, like Russia, has reason to object to the way the history of that war is being rewritten to suit the agendas of ultranationalists in neighbouring countries, and ultimately the aggressive agenda of the US government.

Beijing’s sensitivity over issues like Japanese politicians’ fondness for visits to the Yasukuni shrine to the war dead — which bears the names of 14 convicted Class-A war criminals — is not down to some paranoid fixation with the past, but because there is a powerful revanchist current in Japanese politics that glorifies its war record, a current to which the current prime minister belongs.

Abe’s continued failure to get his way over the constitution is heartening. It is a goal that permanently eluded his murderous grandfather.

In Japan, there will be millions marking the 75th anniversary of the atom bombings whose resolve is to defend the Peace Constitution and oppose militarism and war.

In Britain, those of us who stand for peace and socialism should stand with them: opposing the rewriting of history, opposing the encirclement of China and opposing the sabre-rattling of US-allied governments that risks sparking another terrible conflict.

Ben Chacko

Ben Chacko