This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

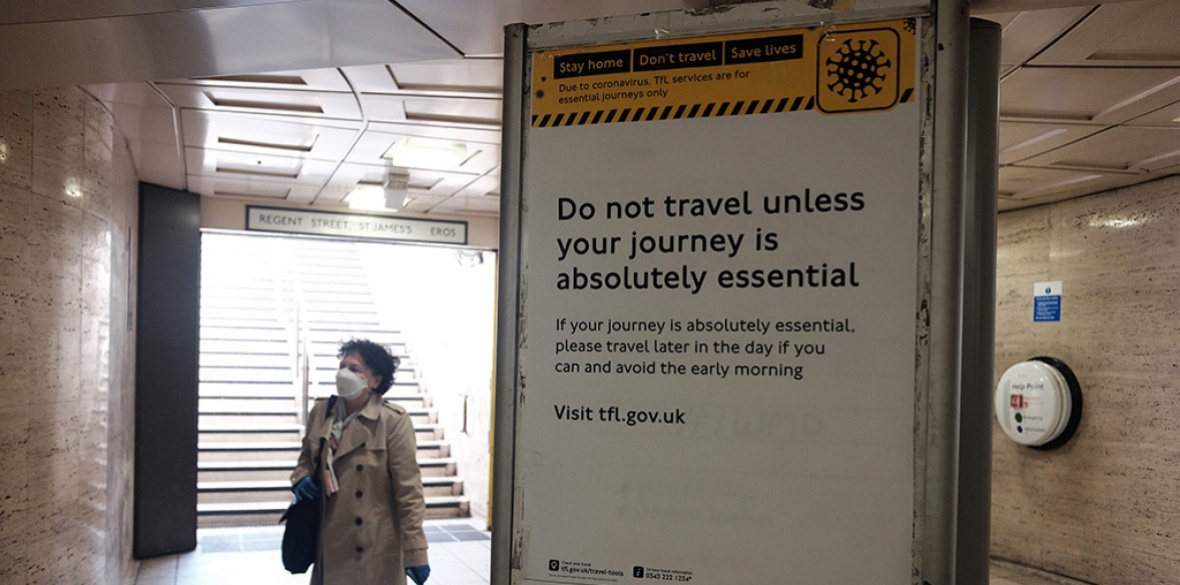

BRITAIN tops the league table of coronavirus deaths per head of population.

With only the US rivalling our country for this dubious distinction, the present Tory government is in line to appear the most irresponsible administration in our history, rivalling the Chamberlain government that by appeasing Hitler made the second world war victory over fascism more costly.

Reports that the Cabinet is divided between a substantial minority — or perhaps even a majority — in favour of the swifter exit from the Covid-19 lockdown than the Prime Minister is presently willing to consider, obscures the reality that decisions in a Conservative Cabinet are critically influenced by a more powerful range of forces than those represented by the maladroit mob seated around the Cabinet room table.

The multiple stories that appeared in the billionaire media suggesting that last Monday was to be a new “liberation day,” in which the constraints imposed on production would be lifted and social life resumed, were the projection of a myriad of conversations among the milieu of bankers and bureaucrats, business “leaders” and beneficiaries of our system of private ownership.

No-one should be surprised that a consensus in favour of putting profit and the resumption of the untrammelled accumulation of surplus value over the health and wellbeing of the people emerges from among these people.

But to make a change in government policy appear credible and to inoculate the government against criticism it must appear as a response to popular opinion, a recognition of a new reality and the necessary stage in recovery.

In this sense, everyone who mingled a bit too closely with family and friends or slacked off the hand-washing and social-distancing advice added credibility to those in the Cabinet who are gung-ho to get away from the lockdown on profits.

Nevertheless, this turn of events presents the parliamentary representatives of the capitalist class with something of a dilemma in that it is they who will pay the immediate personal and political cost of a resumed rise in the level of infection and the deaths that inevitably result.

In this they have been given a degree of political cover by Labour’s focus on the failure of the government — while Boris Johnson was incommunicado in hospital, the infection rate was rising and deaths mounting — to come up with an exit strategy.

In the minds of millions, the priority was not an exit strategy but a containment strategy.

It is worth speculating what might have happened to the uncounted rise in care home deaths if Labour had concentrated more on holding the government to account over the failure of the lack of adequate PPE, or its failure to regulate the largely privatised care home industry.

Much of the justification for privatisation and the disposal of council-owned care homes was the suggestion that risk would be borne by private owners rather than the state.

In the event, the risk is at the expense of our elderly and the people who work in care without adequate personal protection.

When the government’s initial response to the crisis took the form of a massive expenditure to support business and banks, subsidise wages and pay for furloughed workers, some thought this a vindication of Labour’s 2019 election programme.

Even though Labour’s public spending commitments were costed and comparatively modest, they were presented in the media as wildly unrealistic, even though the Tory election pitch had already abandoned — at least in words — the austerity rhetoric of the previous Tory and Liberal Democrat governments and had junked Thatcher’s faux-housewifely justification for limits on public expenditure.

This will be seen as an exercise in wishful thinking.

It is true that superficially rational explanations for the austerity economics and cuts in public expenditure are less easy to defend now that governments, irrespective of their political character, have spent unprecedented sums in containing the coronavirus. But the reality is that the consequences of economic recovery will be vastly uneven.

Already the architect of the Cameron government’s austerity agenda, George Osborne, now the media mouthpiece of a Russian oligarch, has described workers on furlough, soon to experience a further pay cut, as in a waiting room for unemployment.

But it is not only the millions of workers who will have no job to return to but the large numbers of small and medium-sized proprietors, restauranteurs, cafe owners, freelance professionals, shopkeepers, publicans and craftsmen and women who will find their livelihoods at risk.

The immediate priority is to ensure that the lockdown strategy is strictly subordinate to the public health priorities that the trade union movement insists on.

Thus Rishi Sunak’s extension of the furlough scheme is a notable victory for the trade union movement that has compelled a more rational response from the government than first soundings might suggest.

No sector should go back to work until it is demonstrably safe to do so and our trade unions need to have a central role in managing this process.

The TUC set an early benchmark for this and the National Education Union’s five conditions which must be met before schools go back has received emphatic support from shadow education secretary Rebecca Long Bailey.

We need more of this, with Labour’s shadow ministers establishing firm criteria for the resumption of activity in the sectors for which they are responsible.

It is against these conventional criteria that the performance and relevance to millions of workers of a social democratic party is measured.

By this measure, Labour is in trouble. In December 2017 Labour was polling at an encouraging 45 per cent.

Today it has lost a third of that percentage. Compared with most comparable continental parties, it is still in contention as a potential party of government, but that is dependent on the cohesion of the class and ideological alliance that makes its electorally credible.

Gordon Brown, the rising red prince of the Scottish left whose own ideological trajectory took him from authorship of Scotland’s Red Papers to patron saint of the City and the banks, made a fair job of holding Labour’s electoral coalition together with the tax receipts of a ballooning finance sector funding useful social spending.

The 2008 capitalist crisis of financialisation pricked that particular balloon.

In Labour what unites today’s tribes — excluding the faction that willed defeat in order to defenestrate Jeremy Corbyn — is the desire to win elections and, for some, to hold office.

What divides them is what to do in office. Some, the most venal, simply want the perks of the job. Test this thesis by listing the New Labour luminaries who now consult for the private healthcare lobby, decorate the boards of banks or front defence industry corporations.

A more politically respectable element see in government the chance to fine-tune public administration and the country’s regulatory regime to make things work better for a vaguely defined greater good.

A further tendency understands that even a modern capitalist economy with the main productive forces in private ownership is rendered dysfunctional when utilities, public transport, education and health are distorted by their subordination to the profit drive.

In his perceptive piece in the Morning Star on Tuesday, Vince Mills made the point that the party’s left wing, especially Momentum, contains a very wide constellation of opinion.

In doing so, he illuminated the fact that its social composition it is substantially more middle class than the population as a whole, or even Labour’s core vote.

Labour’s electoral base has always consisted of a working-class vote — most solid in places where a decisive proportion of the population depend upon basic industries such as mining, manufacturing, steel and shipbuilding, plus a substantial rural proletarian vote — progressive-minded middle-class people in public administration, health and education and a fair pole of support among professionals, intellectuals, journalists and people in the arts.

The process by which neoliberalism has disaggregated this alliance is principally to do with the way in which the main forces of production have been reconfigured on a global scale.

The reflection of this process in Labour has been the decomposition of its working-class base and the marginalisation of radical socialist thought.

The route to recomposing a winning electoral combination for Labour does not lie in reformulating New Labour’s redundant policy fixes.

The passive submissive style of Labour at present suggests that there exists in its parliamentary leadership little sense that a distinctive policy profile is possible or even desirable.

Nominally the manifesto commitments and conference policies agreed under Jeremy Corbyn remain in existence but at every opportunity these are subverted, denuded of their radical content or simply ignored.

The Tory government is already acting on the truism that every crisis presents an opportunity and is actively intervening to deepen the privatisation of the health service, tilt the balance of power in the workplace further towards employers, use the real threat of redundancy to discipline the workforce and concentrate the coercive powers of the capitalist state.

Labour’s response to the crisis is to refuse the opportunities it presents to propose thoroughgoing changes to the way in which the country is run.

Every day presents a new opportunity to awaken Labour’s appeal to a winning coalition of class and political forces.

But these cannot be seized while the party enters the public consciousness only in the form of an advocate pleading its case before a jury that is already fixed.

As the most vulnerable workers are forced back to work, Labour and the unions need to be their active advocates in the workplace, in the community and on social media in a qualitatively different way, acting in the interest of our class as a whole and for everyone who needs protection from exploitation and oppression.

Nick Wright blogs at 21centurymanifesto.