This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

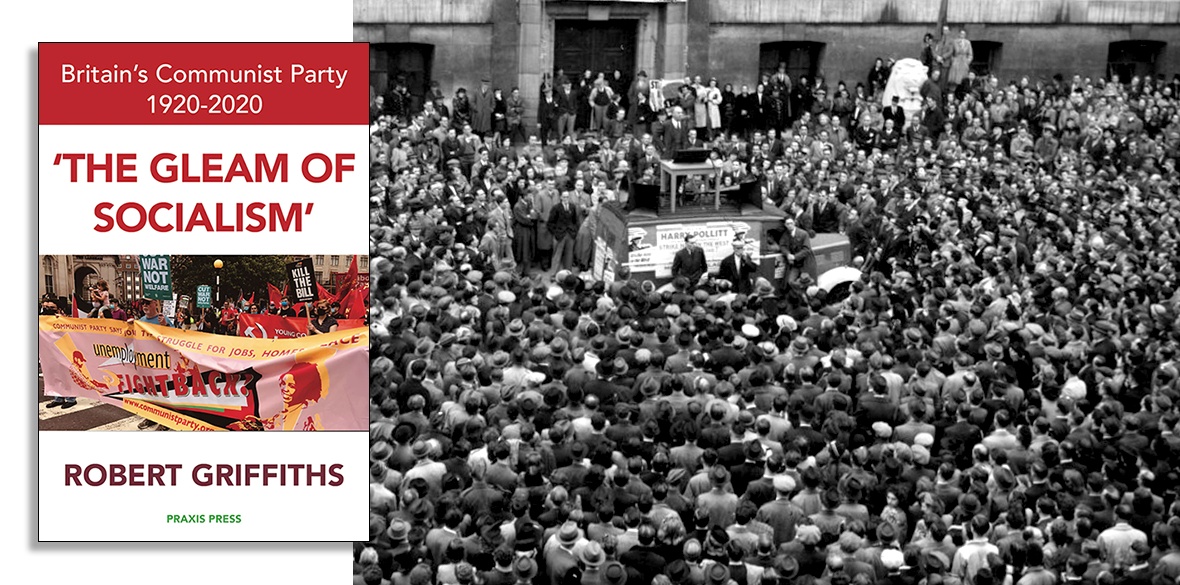

The gleam of socialism: Britain’s Communist Party 1920-2020

Robert Griffiths, Praxis Press, £25

ROBERT GRIFFITHS is the first general secretary of a Communist Party to write a party history.

The book aims to do three things: to speak to the growing number of new joiners; to deal in facts, which are sometimes uncomfortable for the party but always very uncomfortable for the ruling class; and to locate the party in a historical continuity which demonstrates that Marxism is a world outlook of the working class, that also has deep roots in British popular history.

He relates a remarkable history that now spans eleven decades. It involves drama and a bewildering array of political tactics and forms of organisation including the Councils of Action, “Hands off Russia,” National Minority Movement, National Unemployed Workers Movement, Medical Aid for Spain, Anti Racist Alliance, Campaign Against Racist Laws, People’s Convention, People’s Charter, People’s Assembly, Lexit, the LCDTU and the Young Communist League.

He describes triumphs for which the party deserves far more recognition, including: “Hands off Russia,” “Hands off China,” Open the Second Front, very early adoption of opposition to racism as a core principle, “No Cruise Missiles,” anti-apartheid and solidarity with the Palestinian people.

He tells a story of bold intellectual moves to embrace emerging forms of organisation and communities such as those in struggle against racism, for LGBT+ and women’s liberation, and in defence of peace. In particular, the party organised women to play a leading role in society, from the Women’s Hunger March in 1934, the struggle to join unions during WWII, the formation of the National Assembly of Women, for equal pay and the Greenham peace protests.

He describes a party that has stayed true to many political aims throughout its existence, from support for Irish unity (that saw members jailed for gun-running in the 1920s and support for Hunger Strikers in the 1980s), and freedom from colonial rule for Egypt, India and Malaysia, to support for existing socialism in the Soviet Union and China.

Also, how it has long been ahead of the contemporary consensus in the labour movement in the need to explain important developments, from the appeasement of Hitler, joining Nato and the then European Community, to deindustrialisation and financialisation of the economy in the 1980s, and now to the dangers of the ascendancy of military industrial, food and pharmaceutical capital as the shock-troopers of a new ruling-class offensive.

The TUC hierarchy may not have liked the communists, but they always paid attention to their predictions.

Griffiths describes in detail other pioneering political positions taken by the party from opposition to the EU and for popular sovereignty, as well as support for progressive federalism and parliaments for Wales, Scotland and England including an autonomous assembly for Cornwall.

The Communist Party was amongst the first to propose electoral reform in favour of a system of STV in multi-member constituencies. Griffiths shows this was advanced by Willie Gallagher, Communist MP for West Fife, at a wartime parliamentary speakers’ conference on electoral reform.

It took a very early stand in defence of putting people before profit when the pandemic broke in 2020 and has conducted an on and off struggle against reformism which Griffiths explains so ably in a well thought out and lengthy section on “Party crises, recovery and re-establishment 1928-1988.”

Most importantly, Griffiths describes how communists got themselves into these various ideological conflicts, how they got out of them and what impact they had. He describes the Soviet/German pact of Non Aggression signed in 1939, Hungary in 1956, the China/Soviet ideological struggle in the early ’60s and of course, the Czech events in 1968.

Griffiths shows the CP at its best when it swims against the tide — refusing to load the Jolly George, the Invergordon Mutiny, refusing to allow the Jews to be blamed for austerity and war, the legendary volunteer battalion to defend the Spanish Republic, exposing fascist manoeuvres in Finland in 1939-40 and then explaining them in thousands of factory gate meetings.

This was then repeated during the Anglo-Israeli assault on Suez, organising squads to defend communities during the racist riots in Notting Hill, calling for the recall of the fleet during the war in the Malvinas/Falklands and later, playing an important role in mobilising against the Iraq war and warning of the dangers arising from the war in Ukraine.

Griffiths is at his fiery best when writing about the dissolution of the Communist Party by the so-called Eurocommunists, who ended up dissolving themselves within a few years and making off with all the family silver. This crisis, which has been the hardest to recover from, was achieved “in a period when the labour, left-wing movement in Britain and internationally experienced dashed hopes and severe defeats.”

He deals with individual characters, and expect to discover the truth about “Red Robbo,” Thora Silverthorne — champion of the founding of the NHS — past general secretary Gordon McLennan, former Morning Star editor John Haylett, Dora Cox and Annie Powell among others.

Griffiths has also done painstaking research into police and secret service files that are evidence of eavesdropping, opening letters, bugging offices and burglarising party and private premises, stealing information, preventative detention and using violence extensively against Hunger Marchers, to protect Mosley’s fascists, and against poll tax protesters and those supporting striking miners.

It is clear, for example, that during WWII, Herbert Morrison, the Labour home secretary, wanted to ban the Communist Party altogether but was advised against doing so by civil servants and the security services. So he banned the Daily Worker instead.

Griffiths says of the first Labour government of 1924 that “it was in office, but not in power.” The story of the Communist Party is the reverse as it has found ways to deploy political power, without being in office. It is amazing how much impact the Communist Party has had without parliamentary representation, with the struggle of mass movements and tactical ingenuity. Griffiths writes proudly of the role of the Communist Party in forcing the government’s hand on the Second Front, forming the Wales TUC and playing a key role in the establishment of a Scottish Parliament.

Likewise its leadership of the mass extra-parliamentary struggles of the late ’60s and early 1970s led to legislation on equal pay, health and safety and against discrimination at work. These are laws that have been built on and workers still use to improve their lives today.

Griffiths writes as a communist activist and leader who has helped make decisions that define the party’s recent history. He is an established author with a combative style, that employs rigorous standards of research and spurns jargon.

If in the future Griffiths were to write more about the party I think that much could be gained by describing how the inner workings of democracy in the Communist Party have evolved. He demonstrates the organic emergence of the idea of a “British Road to Socialism” but also the creative tensions within it.

But Griffiths knows the power of history as educator, agitator and organiser. So, despite the errors that he does not shirk from describing, he also relates the story as it should be told, with confidence and pride.

Phil Katz is East of England district secretary of the Communist Party.