This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

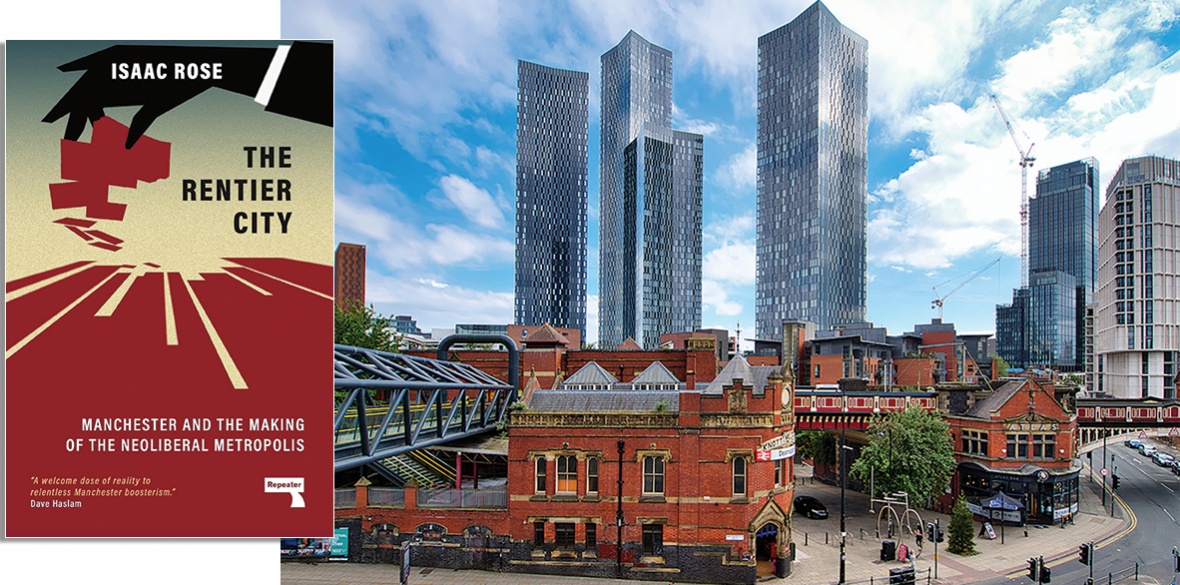

The Rentier City: Manchester and the Making of the Neoliberal Metropolis

Isaac Rose

Repeater Books, £14.99

YOU could be forgiven for thinking that Manchester, with its glittering towers and feverish urban regeneration powered by foreign investment, is a post-industrial city transformed, a worthy competitor to London. Manchester’s PR machine is shouting it from the city’s lofty rooftops.

Isaac Rose is well placed to comment on all this. As an organiser for Greater Manchester Tenants Union, for several years he has worked closely with tenants in the area, challenging housing providers and city planners who treat human beings like cattle, to be shunted here or there in order to maximise private profit.

Through examining the history of the city’s expansion, Isaac Rose tells a story of community resistance, political intrigue and broken dreams of municipal socialism; a city with desperate poverty, dispossession and displacement of the people who, for generations, helped build the city.

The author was not born in Manchester, but, like me, has lived there for 10 years. He writes: “During this time two things have been impossible to ignore — the rapidity of the changing city skyline and the rising rents,“ and I couldn’t agree more.

The front cover depicts a giant silhouetted hand, delicately removing what appears to be a small, crumbling building while shadows of tower blocks loom ominously in the foreground. It perfectly depicts my own fear that the council, investors and developers behave as though the city is little more than a giant Lego set for them to demolish and rebuild at whim, with no consideration of the very real human beings whose lives are ripped apart in the relentless search for profit.

The book is more than just an examination of the dire housing situation. It is an analysis of how this has happened in Manchester and how the political and economic forces in the city over the last two centuries have shaped its transformation.

As he guides us through the last 200 years of the city’s history, we are regaled with anecdotes of past struggles against the rentier class. Those same struggles continue to play out today. It is a relief to know that “Not everybody in the city accepts the narrative of the boosters, nor do they want their city sold off to the highest bidder.”

Council leaders who were at the forefront of rebelling against Thatcher’s rate cap in the ’80s and fighting tooth and nail for municipal socialism ended up abandoning their core principles in favour of pandering to rentier capitalists and corporate developers who are practically gifted high value council land to build luxury flats.

Homes are built, they fall into decline because of lack of investment, they are then declared unsightly problem areas and the people are forced out, the buildings demolished and the whole process starts over. Some lifelong residents have been displaced three times — ripped from their community and support networks and shunted off to start again somewhere else with no thought for the psychological impact this has.

We hear about various public-private partnerships with companies registered in tax havens such as Jersey and the Cayman Islands. There are dark tales of backroom deals with developers, public consultations that are simply a box-ticking exercise, where the decision to wave through redevelopment of areas had already been made and the real concerns of communities fall on deaf ears.

The Rentier City is also peppered with accounts from tenants and community campaigners. We hear their real stories about the impact of clearances including one where a community was forced to leave, their houses demolished to make way for redevelopment, only for the deal with the developer to fall through. This land still lies empty.

Despite these damning accounts, Isaac leaves us with a sense of hope. The energy and cohesion displayed by tenants in fighting this steamroller of neoliberal development is uplifting. His analysis of how the “Manchester Model of urban development” came to be is an important tool for future battles, arming us with a clear guide to the levers and methods that must be overcome and a future vision:

“True public housing — affordable to all at the point of need — must be central to our goal; our wider vision an old one: a world so beautiful and so unobtrusive that all people can become human.”

Exciting, scandalous, fascinating and heartbreaking, this book is an expose of how Manchester became the poster-child for urban regeneration and what that really means for the people who live there.