This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

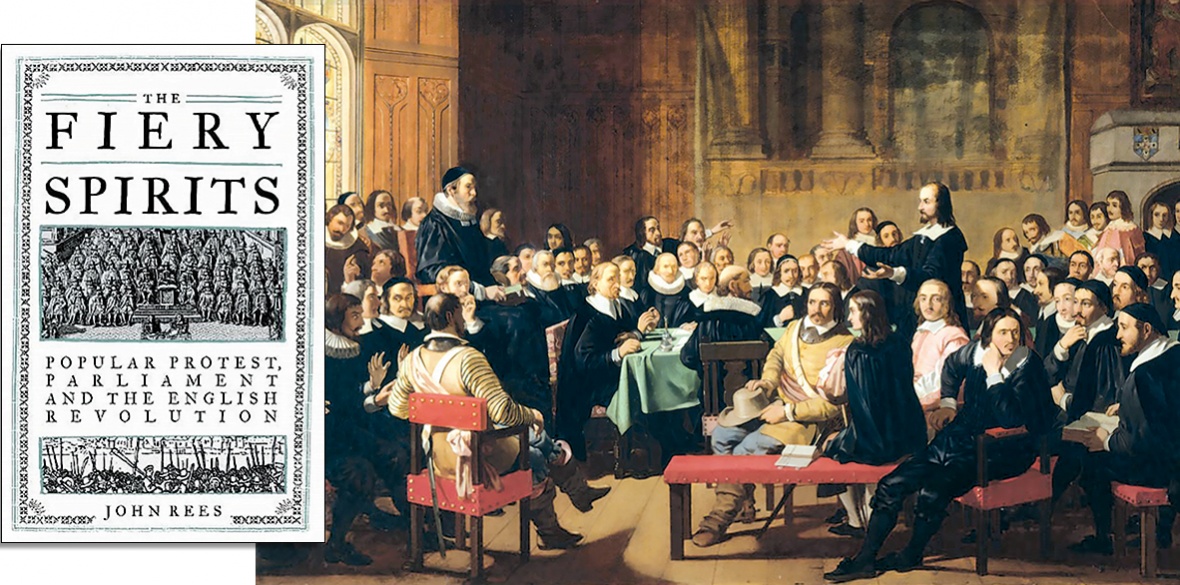

The Fiery Spirits

John Rees, Verso, £30

CONNECTING mass political movements with parliamentary representation is a perennial issue for the left in Britain and, indeed, elsewhere.

It is correct to say that the former — the struggle beyond the Palace of Westminster — is the determining factor in political outcomes, but also true that parliamentary articulation can help shape and empower the movement, even as MPs draw strength from it.

That, it turns out, is a central lesson from the only victorious revolution in British political history, the 17th century struggle for parliamentary supremacy, as explained in this compelling book.

John Rees is already established as the leading contemporary continuer of the Marxist tradition, initiated by Christopher Hill, in writing history of the civil wars of the 17th century. Fiery Spirits will only consolidate that reputation.

The spirits in question are the MPs who championed the popular cause of intransigent struggle against royalism through the 1640s — Henry Marten, Peter Wentworth, Alexander Rigby and William Strode in particular. The term is taken from advice concerning the sources of “tumult and rebellion” penned by King James I to his eldest son Henry, who died before succeeding, leaving a vacancy to be filled by his ill-starred brother Charles.

Their speeches, legislative initiatives and strength of commitment to the parliamentary cause, to the point of rejecting any compromise with Charles when powerful forces were pushing for accommodation, constituted a bridge between the Commons and the popular forces fighting what they saw as a Rome-inspired absolutism.

“This was not simply a one-way process whereby extra-parliamentary agitation influenced speeches and decisions taken in parliament. The committees of parliament could be used to generate popular agitation as well,” Rees writes.

Paradoxically, the parliaments of the time, while elected on the basis of a barely discernible franchise excluding almost everyone from a say in its composition, nevertheless existed in a state of far greater political intimacy with society beyond its walls than is the case today.

It was a site of direct protest by the masses — very largely from London, obviously — often to the point of siege. Petitions are debated almost upon arrival, reports heard and adjudged from sundry officials and numerous committees constituted to deal in detail with particular executive and legal issues: decisions were made, and connected to real life in real time.

At moments, the Commons of the fiery spirits seems closer to a 1917 Russian soviet than the assembly we are familiar with today, as immured by police and procedure as it can be from popular anger.

Rees brings all this out vividly. His dry observation that “the result of [a] series of mass, organised armed demonstrations in Whitehall was a profound alteration in the atmosphere in parliament” is a point to chew on, even if the availability and acceptability of arms no longer sit in a 17th century framing.

Unsurprisingly, the king and his supporters often schemed to remove political debate to safer locations, where royalist bishops would not suffer the indignity of being marooned on barges in the Thames, unable to disembark to take their seats in the Lords by a menacing mobilisation.

Rees also connects the events of the 1640s with those of the late 1620s, when many of the same issues — in particular taxation power — were rehearsed, with many of the same characters playing leading parts.

The social movements of the earlier period, from rural poor fighting for land access through to mutinous unpaid sailors, are given their due credit for shaping the political environment in passages resting on considerable valuable research.

These movements had an elemental and riotous quality: they were the actions of people who would “rather die by the king’s command than see their families perish from hunger” in the words of one group of defrauded sailors, who yet had no direct access to political power.

Rees also guides the reader with lucidity through one of the main besetting complexities of the revolution — the overlay of social dynamics by religious forms and rhetoric as the medium for expressing class interests.

He reminds us that Puritanism was not purely a matter of religion but was entwined with a spirit of resistance to tyranny, and that there was no separation of church and state at the time. The church “was a major landowner and tax authority in its own right. The functions it performed included all or some of those which in modern society are performed by the mass media, the civil service, the welfare system, educational institutions and the police and courts.”

Under these circumstances “every serious argument was a politico-religious dispute involving questions of governance,” turning questions of religion into class issues — “as it began with the Surplice, it must end with the smock,” in a contemporary formulation.

Fiery Spirits avoids didacticism, and largely lets its lessons be drawn by inference. Rees is more explicit in his Marxism and the English Revolution (Whalebone Press, 2024). But this outstanding book’s central theme has extra resonance today, when four MPs serve in the Commons as a direct result of the mass movement of solidarity with the Palestinian people.

And, of course, bishops still sit in the House of Lords.