This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE late EL Doctorow lamented the narrowness of contemporary fiction, suggesting it has “given up the realm of public discourse and the social and political novel.”

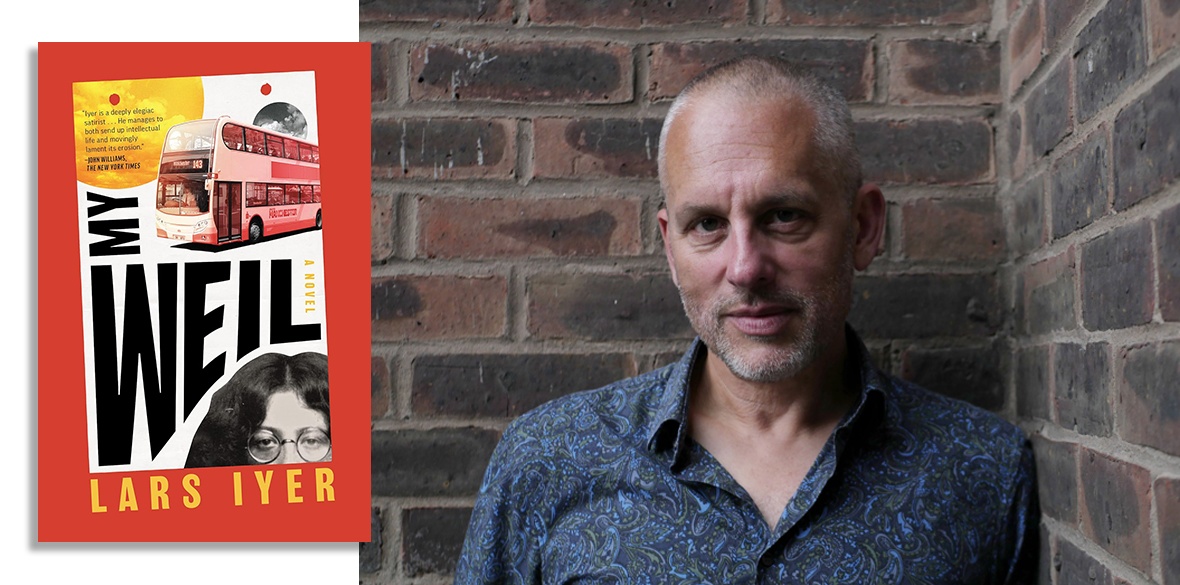

The work of Lars Iyer belies Doctorow’s pessimism. Iyer’s stories are unflinching examinations of the commodification and plunder of our economy, society and culture. What’s more, he’s one of very few writers to make me laugh out loud on the bus to work.

“Laughter is important — it’s necessary to breathe,” says Iyer, citing the Romanian philosopher EM Cioran’s view of writing as an escape from the suffocation of oppression.

“For me, that getting-free involves laughter: laughing at the Man. Laughing at the madness. Laughing at the po-faced and humourless absurdity that is all around us.

“The attraction of comedy [is that] it allows some freedom and perhaps might grant freedom in turn. A way of diagnosing what’s happening to us, but not being crushed by it. Perhaps it might be the beginning of a critique, which is only possible if we can find others to laugh with.”

Collaboration and connection are central to Iyer’s novels. In his latest, My Weil, a group of Manchester-based PhD students grapple with urban decay and the advance of corporate imperialism.

Crammed with erudite discussions that veer into sparkling invective, it highlights the need for robust friendships in terrible times.

It’s an idea captured in a well-known line from David Bowie: “While troubles are rising, we’d rather be scared together than alone.”

“Yes, that’s the thing,” says Iyer. “Despairing together. Sharing such moods, being humorous about them, comically exaggerating them, ringing changes upon them, which means they’re no longer solely negative.

“We might think that we that we can’t do much about the disasters ahead of us — about neuroweaponry or weather warfare, about education capture and health capture, about destabilisation agendas, about transhumanism — but we can discuss and diagnose them. Laughing together at their folly, shaking our heads together at their evil, we needn’t be merely passive victims.”

My Weil savagely satirises the corporatisation, managerial jargon and reductive systems of academia. For me, the character Professor Bollocks — “mic’d up like some boybander” and spouting drivel about “economically manageable skillsets” — triggered a flashback to the Thatcher era, and my time in a research team subject to the scrutiny of an “industrial uncle” (sic).

“Nothing of the novel is exaggerated. The language of management theory has colonised the university. Expressions like ‘best practice’ and ‘seedcorn funding,’ used without irony … No-one laughs or rolls their eyes … Everything, taken straight.”

Iyer despairs at the dominance of management processes emphasising productivity, efficiency and resourcing, and recasting students and academics as “self-initiating entrepreneurs.”

“To make it worse, this process of stripping away meaning, comradeship, a sense of the absurd is accompanied by the grotesque parodying of the same notions that the process hollows out: the university as your ‘family,’ your fellow students as potential ‘buddies.’

“My characters, in response, cultivate counter-techniques of failure and ineffectiveness, of wandering and vagueness and of displacing ends from means.

“They aim at a deliberate incompetence, in which not finishing your PhD dissertation is more of a sign of honour than completing it on time; in which failure is a better sign of scholarly integrity than system-rewarded success. And they laugh, they have fun, which is pretty much forbidden in these overserious times.”

There’s a strong sense of communality in My Weil, but the postgraduate characters seem mired in chaos and inertia. Is Iyer sceptical about the possibility of collective action?

“The characters consider various possibilities for collective action. There’s becoming lumpenproletariat: living like the raggle-taggle of criminal-types, the unmanageable declasses that Marx wrote about, who keep to the shadows.

“There’s becoming apocalyptic: gathering like the early Christians awaiting the second coming, only this time, they’re waiting for an incoming, shattering transcendence that would explode the present order of the world.

“There’s secession: going under the state, on the model of villages in Alpine valleys that that have their own currency, that keep low-tech using mechanics, not electronics like those parts of Mexico that just do their own thing, regardless of central government decree.

“My characters have little faith in present institutions. My question would be whether and how we might make them more accountable, transparent and democratic.

“My characters are tired of all that. Perhaps we can see a viable form of collective action — or rather, collective inaction — in their common drifting, their vagueness, their abandonment of proper ends.”

There’s a touch of the New Weird to My Weil. As the characters become increasingly deranged by their fears, one experiences a prophetic vision of unbearable repression and seeks a solution in myth. And then there’s a strange zone known as The Ees.

Iyer explains: “The Ees, a scrap of woodland in Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Manchester — meant to resemble the Zone from Tarkovsky’s film Stalker — permits the wandering and vagueness, the displacement of ends from means. It’s about disactivation, which is why it’s full of all kinds of junk.

“As such, the Ees is an embodiment of the students’ relationship to their PhD dissertations and, more broadly, to study. It allows them to be stupid, ignorant, disoriented … but in a positive sense. In an antidote to Professor Bollocks’ kind of sense.”

The novel’s satire, characters and apocalyptic mood are firmly grounded in its setting, postindustrial Manchester, a city still haunted by the echoes of Joy Division and the throbbing dancefloor of the Hacienda. I ask Iyer what fascinates him about the music and culture of 1980s Manchester.

“The Manchester I discovered when I moved there in 1989 still had areas that were like the Ees of my novel: unproductive areas, temporary autonomous zones such as the Hulme Crescents, an edgy zone of low-rise, system-built flats.

“It was from such places that so much great Mancunian culture came. Manchester was regenerated in the ’90s. Investors and financiers, gentrifiers and speculators transformed the cityscape with statement architecture, with steel-balconied warehouse conversions: monuments to cheap credit.

“My characters dream of battering back the Mancunian regenerators, of reopening the figurative cracks and the crevices where you used to be able to live unnoticed and unbothered on government benefits.

“Only the Ees is left to them of that world now. The Ees, and the great Mancunian music to which they still listen.”

Finally, I ask Iyer if he believes humanity is doomed.

“Not if we awaken to what’s happening. What will save us? Human unmanageability, perhaps. It’s just such unmanageability that is shown in my characters’ laughter, in their friendship. Internal struggles between various factions of the powers-that-shouldn’t-be, perhaps. Something contingent, miraculous, perhaps.”

My Weil by Lars Iyer is published by Melville House, £14.99.