This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

FERNAND LEGER (1881-1955) grasped life with insatiable optimism and a passion for ideas. He was born in Normandy to a belligerent cattle merchant who died during his early childhood, leaving an impoverished widow. She apprenticed the 16-year-old Leger to an architect, but, in 1900, he fulfilled his desire to study art in Paris, by supporting himself as an architectural draughtsman.

He had grasped the full significance of the recent revolutionary Cubist and Futurist innovations and used them to convey the modernity of urban life, with its simultaneous cacophony of sounds, speeding motorised vehicles and visual stimulation.

But it was soldiering as a WW1 sapper which fundamentally shaped his life. Having left his avant-garde milieu, he found himself in the trenches with miners, labourers, artisans and bargemen. He said he discovered “such humour, such inventors of every day poetic imagery” that he wanted his paintings “to be as tough as their slang, to have the same direct precision … it was there that I found the true nature of what my painting was to be.”

Soldiers Playing Cards, painted in 1917, begins Tate Liverpool’s exhibition Fernand Leger: New Times, New Pleasures and it is not pleasant to look at. The soldiers are morphed into robots, their hollow bodies made of spent shell castings and hands of cartridge clips — the detritus of weapons with which they kill and are killed.

Yet they are grouped in a convivial semi-circle, enjoying their pipes and card game. Dehumanised by mechanical warfare they cling to the normality of daily life. Painted in hospital, as Leger convalesced from being gassed, the painting condemns the hell inflicted on the populace, while celebrating its will to survive.

Leger’s interwar works throb with the vitality and excitement of the machine age. They are replete with abstracted shapes of the cogs and wheels of technological inventions, the billowing smoke and steam from trains and chimneys and the raw colour and urgent messages of wall advertisements. He prophesied that “colour takes a stand. It is going to dominate everyday life and one will have to come to terms with it.”

Yet these motifs exist within structured compositions often based on verticals and horizontals, creating a classical orderliness within busyness. Painted in flat areas of bright, often primary colours, a century later these works still epitomise modernity. Yet the abstracted subjects can be difficult to decipher.

Already convinced of the social necessity of art since the early 1920s, Leger became a committed socialist by mid-1930s Popular Front politics. He was active in the Maison de la Culture, a revolutionary cultural centre, and engaged in the international quest to solve the conundrum of producing a widely accessible, realist art stylistically suited to modern times. His work became more legible and monumental with subjects centred on people or nature.

For the Paris 1937 International Exhibition, he collaborated with Charlotte Perriand on the temporary photomontage mural Essential Joys, New Pleasures, whose celebration of popular culture cocked a snook at fascist cultural and political oppression.

After spending WWII in the US, Leger returned to Paris in 1945 and joined the Communist Party, from which he never wavered. It clarified his ideological outlook, providing a springboard for his last and greatest creative phase.

Inspired by the directness and simplicity of paintings by Louis David, artist of the French revolution, Leger updated his classicism and returned to thematic content, which modernists had virulently rejected since the 1880s. Leger’s calm and optimistic portrayals of working-class life also contradicted the dominant Western postwar aesthetic which privileged abstraction and denigrated realism and political art.

Leisure: Homage to Louis David of 1948-9 is a masterpiece of modernist classicism. Circus performers and workers in their Sunday best meet on a day out in the countryside, a result of leisure time brought by the pre-war struggle for the 48-hour week. They face us relaxed, confident, their limbs convivially linked, as for a group photograph.

Their bicycles epitomise the democratisation and liberation of working-class mobility, while the white doves and flowering and seeded plants signify postwar peace and plenty.

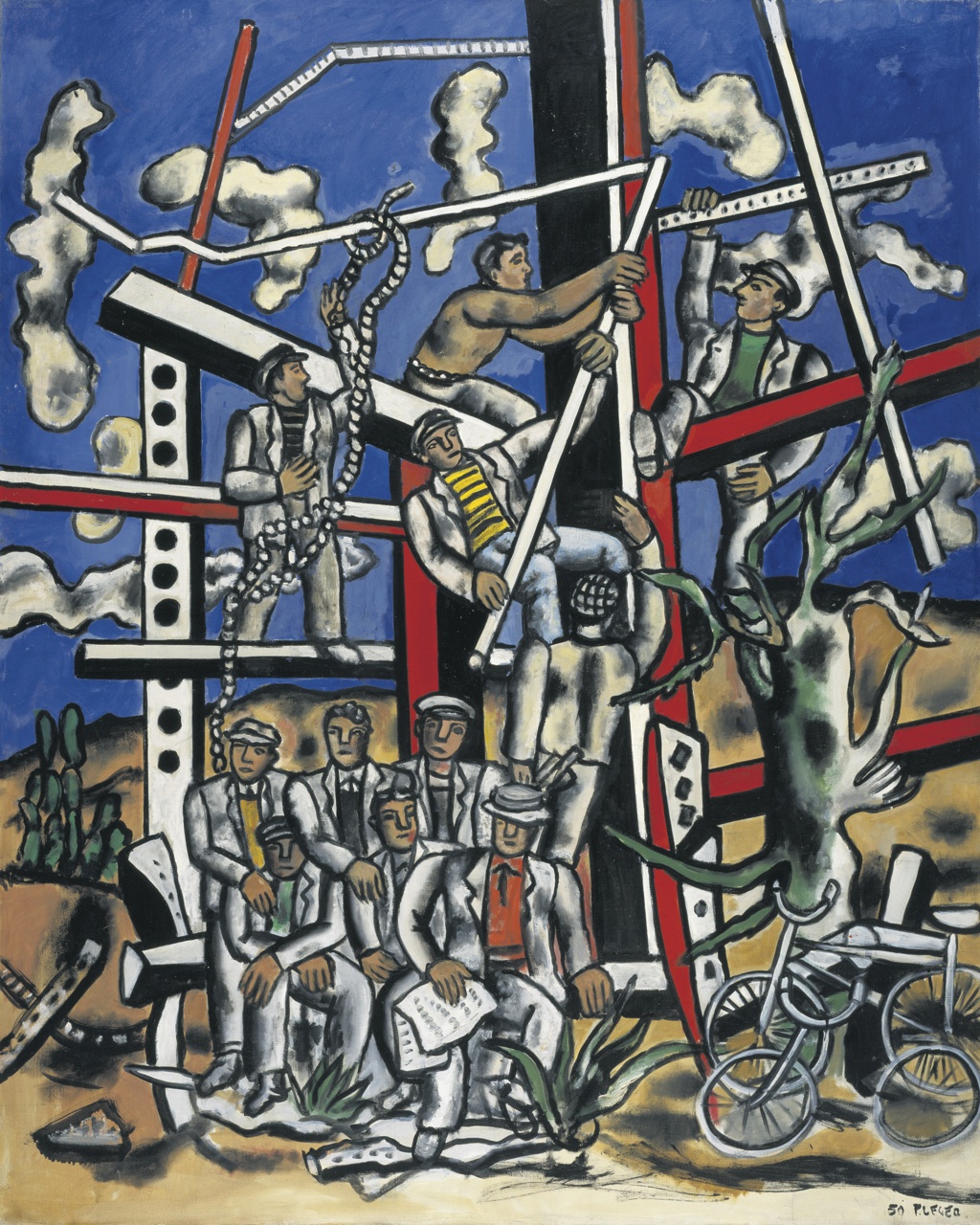

In his major series The Constructors, the workers are also individualised but linked when building massive electrical pylons. Men, metal and sky form maximum contrast. Painted predominantly in the colours of the French tricolour, the series honours the dangerous and skilled work which brought technological progress to rural France.

This exhibition is pure joy. Curated with deftness and expertise, it highlights the lesser-known breadth of Leger’s media and his enjoyment of collaboration. Leger’s films, his large mural and his fluid, joyful drawings and designs in books, magazines and textiles are all on show as well as seminal paintings.

Unlike the London galleries block-busters it neither overwhelms nor exhausts, while providing a comprehensive overview.

Not to be missed.

Fernand Leger: New Times, New Pleasures runs at Tate Liverpool until March 17, box office: tate.org.uk.