This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

AMONG the pantheon of fan-favourite British heavyweight fighters of all time, Joe Bugner is one name that doesn’t immediately jump out, which, given his record and legacy, belongs in the box marked travesty.

Though his was a career that stretched from the 1960s all that way up into the 1990s, Joe Bugner is most synonymous with the 1970s, along with such cultural artefacts as flared jeans and long hair for young male hipsters; T-Rex, Slade and The Glitter Band for those old enough to remember when glam rock was a thing; the three-day week and power cuts; and also such TV classics as Love Thy Neighbour, Bless This House, George and Mildred, and Grange Hill.

Joe Bugner — like John Conteh, John H Stacey, Dave Boy Green, and Charlie Magri — flew the flag for Britain throughout that tumultuous decade, but did so while being much maligned.

Legendary Scottish boxing and sportswriter Hugh McIlvanney once opined in one of his widely read columns, for example, that “Joe Bugner possesses the physique of a Greek statue but with fewer moves.” Michael Parkinson in a 1974 episode of his then hugely popular show on the BBC derided Bugner as a “bum.” This he did during an interview with Muhammad Ali and despite the fact that at the time Bugner was ranked three in the world.

Just imagine for a moment being a young man in your twenties and having dedicated your life to the hardest sport there is, watching the country’s premier talk show host dismissing you on air to an audience of tens of millions of viewers as a “bum.” You’d have to be made of special stuff for it not to floor, never mind affect, you.

Joe Bugner was born Jozsef Kreul Bugner in 1950 in a small village in southern Hungary. His family fled Hungary for Britain in the late 1950s after the 1956 Soviet invasion. His initial foray into boxing began in the early ’60s in the amateur ranks, in which he fought 16 times and lost three.

Encouraged by his amateur trainer to turn pro, he did so in 1967 at age 17. After three years of fighting in near complete anonymity, he burst onto the world professional scene in 1970, a year in which he fought an astonishing nine times without loss, defeating among others Chuck Wepner of the United States and British heavyweight stalwart Brian London.

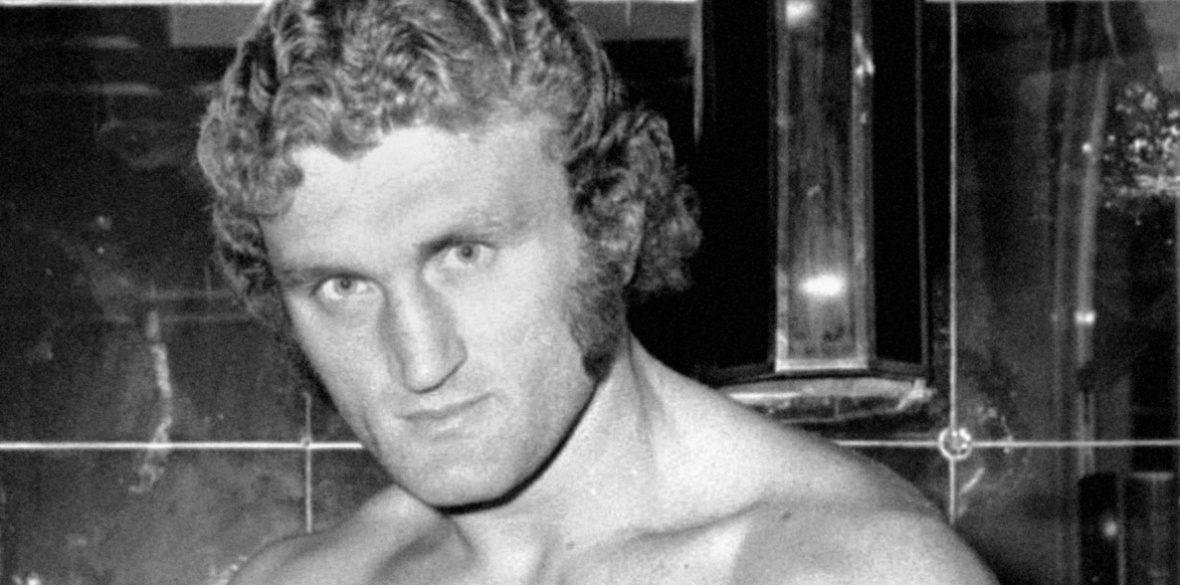

At 6ft 4in with striking blonde hair and blue eyes, Bugner certainly was the impressive physical specimen Hugh McIlvanney described. He carried a stiff left jab, had decent feet, and a good engine in the era of 15-round-bouts. He was fairly easy to hit though, and lacking the power of many of his counterparts, the majority of his victories came on points after going the distance.

On March 16 1971, Bugner faced Henry Cooper at Wembley’s Empire Pool in London for the British, Commonwealth and European titles. Cooper by then was a national treasure and so Bugner’s victory by way of a controversial points decision saw him caricatured as a pantomime villain, an impostor who was never able to win the acclaim and affections of the British boxing public. Indeed, from that point on he was no longer British but a Hungarian refugee masquerading as such.

Just six months later Bugner lost his titles to fellow Brit Jack Bodell, again at the Empire Pool in London. Undeterred, he continued on and managed to claw his way back into contention. On February 14 1973 he entered the ring at the Convention Centre, Las Vegas, to face his biggest test yet against none other than Muhammad Ali.

This was a non-title bout, but nonetheless it introduced Bugner to US fight fans and he did not disappoint, taking Ali the 15-round distance. Five months later on July 2, he fought another ring legend in the shape of Joe Frazier, again in a non-title bout. This fight took place at London’s Earls Court, and though losing on points, against an in-prime Frazier it is considered by many to have been Bugner’s finest-ever performance.

Bugner fought Ali again in 1975, this time for the latter’s WBA and WBC world heavyweight titles. Fighting in the sweltering heat of Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, Bugner did more holding than fighting against Ali and though lasting the 15-round distance, he was roundly panned by the writers at ringside not to mention the many fans who’d taken the trouble to tune in at home. One US boxing writer quipped afterwards: “To win a world title, a boxer has to be prepared to die, but Bugner wasn't even prepared to try.”

Fortune smiled on Bugner again in 1976, though, when he regained his British, Commonwealth and European titles against Richard Dunn at Wembley in front of a sold-out crowd, which was solidly behind Dunn going in. Regardless, Bugner came out swinging from the opening bell and had Dunn down on the canvas just six seconds in. Dunn got up but quickly found himself down again on the back of a straight right hand while pinned against the ropes. With Harry Carpenter providing commentary at ringside, Bugner went on to close the show with a spectacular first round KO.

Bugner was part of a heavyweight generation of fighters who stayed in the game too long. In 1987 he faced Frank Bruno at the old home of Tottenham Hotspur FC, White Hart Lane, in another classic domestic dust-up. It wasn’t to be his night and he got stopped in the 8th round by the much younger and stronger man.

Bugner wisely retired after the Bruno fight, only to unwisely return to the ring eight years later in 1995 against the unknown Vince Cervi in a non-title bout at the Carrara Sports Complex in Queensland, Australia — a country to which the Brit had by then decamped with his wife and kids to start a new life.

Joe Bugner’s final ring outing came in 1999. A win by disqualification against another unknown opponent brought to a close a decades-long boxing career that saw him fight some of the most iconic and legendary heavyweights of all time.

Sadly, in 2023 it was revealed that Joe Bugner, by now in his late-seventies, was living in a care home in Australia, struggling with severe dementia to the point of no longer remembering anything of note about his long ring career.

Fortunately, there are many of us who still do.