This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Picasso 1932 — Love, Fame, Tragedy

Tate Modern

London SW1

Despite its rather misleading title, erotic love is the overarching subject of Tate Modern’s Picasso 1932, Love, Fame, Tragedy. Indeed, when first shown in Paris this extensive exhibition was more explicitly titled Picasso 1932 — Année erotique (erotic year).

This emphasis is clear from the selection of works, their captions and the wall texts, which are reproduced in the accompanying free booklet, and in some large statements by Picasso painted on the walls like “Essentially there is only love. Whatever that may be.”

Picasso’s muse was his young and illicit lover Marie-Therese Walter, whose long-limbed body and Grecian profile had arrested his gaze in a Paris boulevard in 1927. His cliched, but prophetic, chat-up line was “I feel we could do great things together.” And they did. She was not yet 18, he was 45.

She proved to be a terrific muse and a spirited and intriguing companion.

But Picasso was married to his socially conservative wife, having to keep his relationship with Marie-Therese a secret, and the consequent periods of separation perhaps added drama, emotional piquancy and longevity to their passion.

By 1932, although they had been lovers for five years, Picasso still continued to pay homage to their love in works which are among western art’s frankest and most moving expressions of male love and sexual desire for women.

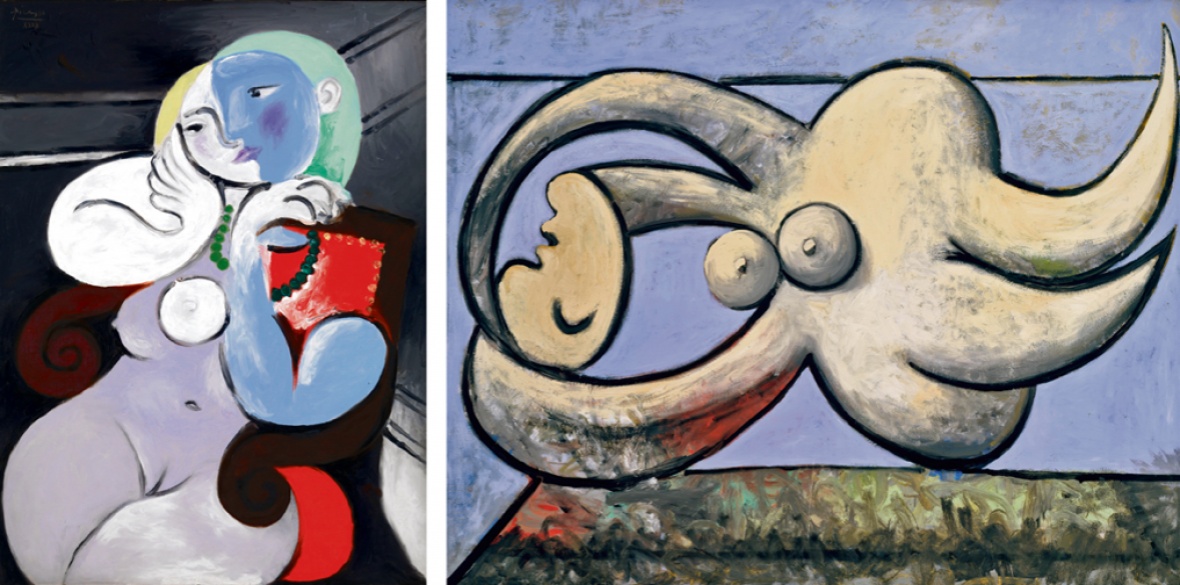

Marie-Therese’s classical profile, globular breasts and athletic body appears repeatedly in paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, ranging from the tender Nude Woman in a Red Armchair to the wild distorted Reclining Nude and the enigmatic Bust of a Woman. We see her myriad moods and actions — pensive, aloof, coy, stubborn, dreamy. Passive or energetic she plays music, swims, reads or transmutes into a classical bust. But most often she is uninhibited, head thrown back, mouth wide open, either asleep or in the throes of sexual ecstasy.

But, as TJ Clark and Achim Borchardt-Hume both point out in the catalogue, Picasso’s subjects were primarily springboards from which to explore formal problems and address contemporary aesthetic issues rather than solely being expressions of his feelings or personal dilemmas.

During the inter-war “battle of the styles” when figurative art was attacked as outdated by abstraction and surrealism, for Picasso and others the foremost issue was discovering viable contemporary visual languages through which to assert figuration’s continuing relevance

It is not unusual for an artist to focus on a single subject as a means of exploring stylistic variations in order to generate different meanings, especially within the time span of only one year. Familiarity with the subject frees the artist to concentrate on formal experimentation.

Marie-Therese’s profile that dominates these works was the perfect subject for Picasso’s re-evaluation of classical Greek art, as was his sudden engagement with the tradition of sculptural busts.

For a pioneer of the pre-WW1 avant-garde, who had rebelled against the 19th century classical canon, this “return” was a courageous aesthetic confrontation.

With insatiable inventiveness Picasso arrived at crazy distorted forms, playfully comical imagery or quietly lyrical paintings such as those of his Normandy village of Boisgeloup. Indeed the latter are among the welcome surprises in this exhibition as are his expressions of sorrow in savage drawings of the Crucifixion.

The unifying thread in this riot of experimentation is a claim to liberty, both of artistic expression and of liberation from the stifling hypocrisy of bourgeois social norms. In the 1930s when speaking openly of sex in mixed company was taboo, his explicit figurative paintings were more shockingly honest than many of the Surrealists’.

The curators’ justification for the exhibition’s themes is that 1932 saw major turning points in Picasso’s life and work, through “love, fame and tragedy.”

The first two can be justified, although the single room devoted to “fame” reflects the current art historical focus on critical reception, artists’ social status and their symbiotic relationship with the art market.

Tragedy is the most tenuous part of the narrative, consisting of brief references to Picasso’s future personal problems in 1935 and to the forthcoming deterioration in the socio-political situation on the last room’s wall text.

Yet the socio-political deprivation and insecurities of the Great Depression in 1932 are not mentioned throughout all the previous rooms, apart from rueing its effects on the art market. Nor any mention of the political progress brought to Picasso’s native Spain by its recently formed republic.

Yet by focusing on a single year the exhibition vividly shows how amazingly prolific Picasso was. As we move through rooms filled with large paintings, drawings and sculptures created from January through to December, we can but marvel at his restless energy and inventiveness. And it is a joy to see such marvellous works by one of the 20th century’s greatest artists.

Until September 9 2018. Click here for tickets and more information.