This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

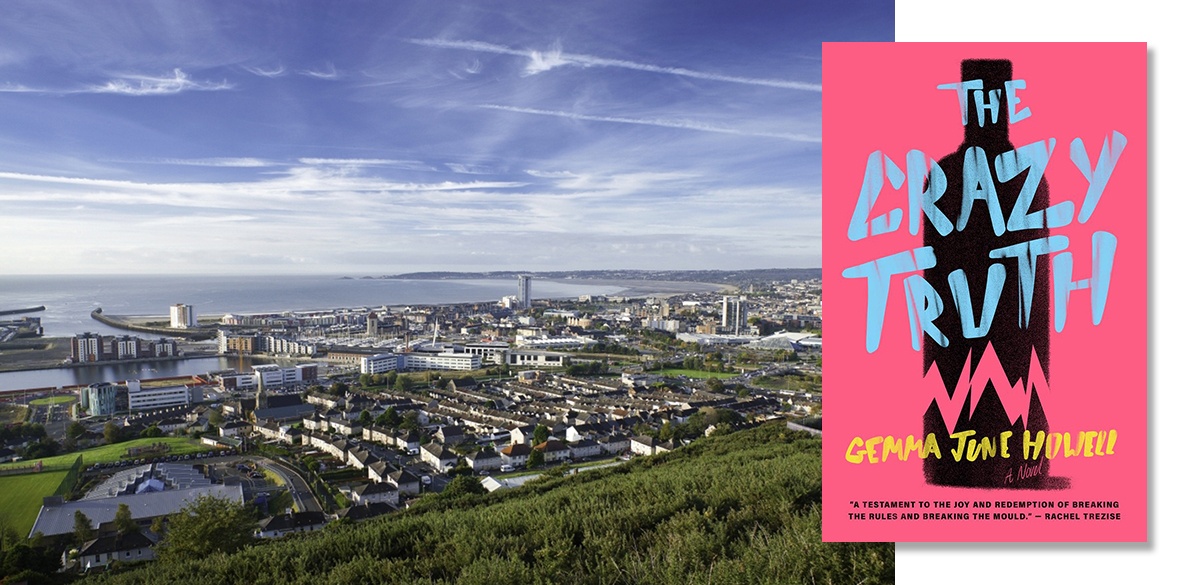

The Crazy Truth

Gemma June Howell, Seren, £9.99

THE CRAZY TRUTH is a working-class novel that remains true to its roots — unflinchingly honest to the point of brutal, yet also touching, funny, human and ultimately uplifting.

It tells the story of Girlo Wolf, born in 1984 into a world of pickets and poverty. Struggling with her mental health and the backlash of childhood trauma, she falls into a dark underworld of sex, drugs and alcohol. Driven by the stories of home, she finds freedom in writing and strives to become a poet, discovering that her words are a route to recovery and survivorhood.

Spanning four decades, Girlo’s story is interwoven with those of her mother and grandmother, making this a powerful tribute to the intergenerational struggles of working-class people.

In this, her debut novel, Swansea-based author Gemma June Howell draws on her lived experiences to present a raw, authentic coming-of-age story. The narrative is non-linear, bouncing about through alternating timelines and perspectives, echoing the chaotic inner dialogue of Girlo herself.

This is no easy read. Howell’s prose is fierce, furious and heartfelt. There’s a pounding urgency that runs through the book, together with a visceral imagery which doesn’t flinch from bodily fluids and graphic descriptions. It’s not for the faint-hearted.

What lifts the novel beyond just being a rip-roaring story is its ultimate message of redemption, framed within a socialist and feminist perspective. The character of Girlo refuses to be confined by others’ expectations of her — a realisation that’s evident both in her breaking away from the men who have tried to do so, and also in her self-discovery as a poet.

When she breaks, finally, from a man from a different social background to herself, she realises how quickly she has become subsumed into his identity: “He couldn’t keep up with her. She didn’t feel at home in herself, let alone with him. He’d modified her to his specification. With him, she wasn’t human.”

Similarly, she refuses to be constrained as a writer: “It wasn’t that she couldn’t write, just that she was made to feel like she didn’t have the right to. She’d gone to a comprehensive school with its limited curriculum designed to prepare its pupils for ‘useful’ work. Writing was for the elite.”

To me, this has echoes of Marx’s theory of working-class struggle — the fight to break through the confines of class barriers and centuries of patriarchal conditioning, to recognise that working-class voices have not just a right but a need to be heard.

Interspersed with the narrative, throughout the book, are Girlo’s poems, written into the shapes of the objects or ideas that consume her attention — a doll, a bottle of vodka, a penis, a gun. The poems offer a dialogue with the prose. Through them, we see the writer’s inner thoughts, often developing through in real time.

It’s an unusual technique, and not one I’ve seen before, but definitely added to my enjoyment of the book. A standout for me is Warman, a poem I immediately fell in love with when I first heard it performed live by the author, and which beautifully and powerfully sums up every woman’s rage at being treated as sexual object, dead-eyed trophy or predator’s plaything.

Also notable is the dialogue, much of which is written in the local Valleys dialect. As someone who is more than familiar with this part of the world, I found it easy to follow, and added realism and authenticity.

How to sum up this book? Much like the woman whose story it tells, it is complex, multi-layered, a combination of the facets of life experiences, both good and bad, a tough shell concealing a huge heart, all underlain by a steely grit, a determination not to be anyone’s victim but to rise up, shouting.

It feels like the start of something. A clarion call. Perhaps it gives us all permission to be something more, to — as the writer says, in a kind of manifesto — “take life by the scruff of the neck, live it to its fullest and write not from an ivory tower but from your sacred fount. From life itself.”

Rebecca Lowe is a journalist, poet and peace activist, based in Wales. She is a Bread and Roses Spoken Word 2020 Award winner.

This is an abridged version of an article that first appeared in Culture Matters