This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

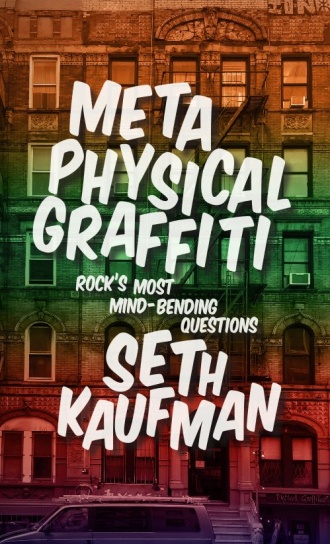

Metaphysical Graffiti: Rock’s most mind-bending questions

by Seth Kaufman

(O/R Books, £14.99)

ERUDITE, caustic and hilarious, Seth Kaufman’s essays in Metaphysical Graffiti are creative non-fiction writing at its best. He uses lists, anecdotes, mock-Socratic dialogues and dramatic pastiche to condemn hype and celebrate authenticity and audacity.

Kaufman takes pains to define “audacity,” citing the smart satire, purposeful virtuosity and musical game-playing of Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick. But 2112 by Rush, a celebration of the “odious anti-collectivist philosophy of Ayn Rand,” self-indulgent and pretentious, is no risk-taker.

I share his dislike of Rush’s squawking vocals, nasty politics and trite imagery but, as he says, it’s a matter of taste. The subjective nature of aesthetic sensibility is set up and analysed in chapters posing exacting questions such as “Beatles or Stones?” and “Billy Joel, Really?”

His knockabout discussion of our psychological attachment to certain bands, and comic assault on the insincere and cynical craftsmanship of the creator of Uptown Girl, are Trojan horses for more serious reflections on the damaging impact of segmented and personalised marketing.

The unifying theme of the essays, established in a chapter based around a rap parody of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, is that modern means of distributing music create “echo chamber music.”

Taste used to be influenced by New Musical Express, John Peel and the PA system in our high street music shops but modern audiences are swayed by data-driven smartphone apps that calculate that a liking for Katy Perry suggests an interest in Nicki Minaj.

Kaufman believes that music was more original and emotionally truthful in the days when enthusiasms were more spontaneous and different styles were “lumped together in some kind of zeitgeistian, hodgepodge feed.” This is unlikely to change, he suggests, as long as mega-rich music companies control our access to culture.

The writer reserves his sharpest barbs for sampled, programmed and sequenced EDM – electronic dance music. Music isn’t always about the instrumental virtuosity of a Jimi Hendrix, he concedes, it can also be about the emotional power of a vocalist or the stagecraft of performers such as John Lydon or Mick Jagger.

But he has little respect for the fist-pumping EDM DJs who “don’t actually play anything, except, perhaps, the fans who shell out major bucks to see them.”

Other chapters deal with musical cults, bizarre stereotypes about drummers and the complex images of theft, homage, influence and impersonation.

Provocative, informative and funny, Metaphysical Graffiti reminds us that music criticism at its best isn’t merely important, it’s also a source of joy.