This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

SOME of the biggest clubs in the world have strong leftist elements, like Celtic, Liverpool, Boca Juniors and Olympique de Marseille.

Meanwhile German second-tier outfit St Pauli remains a global lightning rod for the left’s football network, with fan groups across the globe from Buffalo to Belfast, and friendships with clubs throughout Europe, many of whom we have covered in this series.

Then there are less well known but equally passionate antifa fan groups around the world, from Standard Liege (Belgium), Adana Demirspor (Turkey), Virtus Verona (Italy), Portland Timbers and Seattle Sounders (United States) and Tennis Borussia Berlin (Germany), to non-league clubs like Clapton in east London and Altona 93 in Hamburg.

Here we focus on five more sides fighting the good fight against the tide of right-wing animus.

Hapoel Tel Aviv

“Hapoel,” translates as “The Worker,” and their hammer and sickle badge reflects the club’s historic ties to Marxism, socialism and the working class.

With the club’s previous connections to the trade union movement and Maki, the Israeli Communist Party, fans continue to wave Che Guevara and Karl Marx flags for a club that remains the standard-bearer for the Israeli left.

The depth of fan feeling is often expressed in their rivalry with Beitar Jerusalem, a club with known far-right sympathies, unofficial links to the Likud party and fans infamous for chanting “Death to Arabs.”

Beitar remains the only club to have never signed an Arab player. When the club signed two Chechen Muslims in 2013, fans protested.

When one of them, Zaur Sadayev, scored his first goal for the club, hundreds of fans walked out.

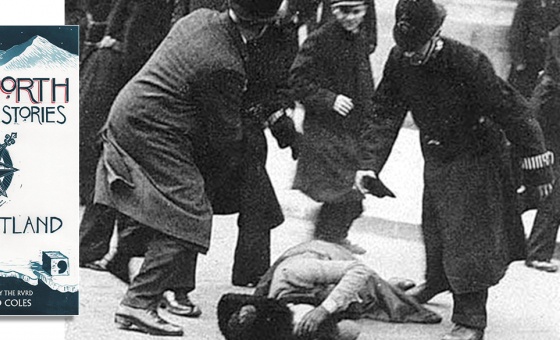

Though they are separated by more than 60km, theirs remains the fiercest rivalry in Israeli sport, one that has been characterised by violence off the field, reflecting the polar opposites of the political spectrum they inhabit.

The Ultras Hapoel website describes Beitar Jerusalem simply as: “Possibly the most repulsive club on Earth. Fascist, racist fans, with management that goes along with them.”

The sun has shone on the righteous though, with Hapoel being crowned Israeli Champions 13 times to Beitar’s six.

AEK Athens

Many AEK fans live in traditional left-leaning neighbourhoods of the city and have formed a “triangle of brotherhood” on ideological grounds with fan groups in Marseille and Livorno, along with links with St Pauli.

AEK are 12-time winners of the Greek Super League but came from humble beginnings.

The club were founded by Greek refugees from Constantinople and it is said this is the reason that the club has anti-fascism and leftism at its core.

AC Omonia Nicosia

Omonia are traditionally regarded as the club of Cyprus’s working class. They were founded in 1948 during the Greek civil war.

The war pitted the Greek government, backed by the US and Britain, against the Greek left, backed by Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Albania.

The Cypriot football authorities insisted that all professional athletes denounce the Greek left and the Greek Communist Party.

Some of those who refused to sign the declaration formed Omonia. They soon became the most popular and successful team on the island, with 20 Championships under their belt.

Fans have tended to associate themselves with the Progressive Party of Working People and the image of Che Guevara has been a recurring sight at their stadium.

The team’s ultra group, Gate-9, developed a relationship with other left-wing supporters such as Hapoel Tel Aviv and Standard Liege.

However, in 2018 and after years of financial problems, the club were taken over by a private company for the first time, prompting Gate-9 and the entire north stand to display a giant red flag with the hammer and sickle on it, in protest, and as a reminder of the club’s history.

Gate-9 insist that the club, now managed by Henning Berg, have relinquished their place as the “people’s club” and have formed a phoenix club, People’s Athletic Club “Omonoia,” in an amateur league, to honour the proud heritage of leftist football in Nicosia.

Bahia

The team from Brazil’s north-east city of Salvador don’t have a long history of progressive politics, but in 2013 a fan group called Democracia Tricolor took over and began to address the social issues the fans cared about.

The president, Guilherme Bellantani, focused on securing the club financially, improving the performance on the pitch and “affirmative actions.”

These actions saw the club fight for the rights of Brazil’s oppressed groups, using the players’ shirts for political symbolism, from depicting oil spills to highlighting historic black Brazilian leaders.

They don’t honour women’s rights one day a year, they do so all year round, just as they do the rights of indigenous peoples.

The club and manager Roger Machado have been vocal in the condemnation of racism in Brazilian society and their support for women’s and LGBTQ rights. The players, too, are happy to defend less populist causes.

They believe their work is beginning to have an impact on Brazilian football and they hope, in turn, society.

They use their place at the heart of their city to unite people and promote a fairer society. They have been accused of being a communist club, but they tend to think of themselves as simply humanitarian.

Bahia also reduced ticket prices to an affordable level for a region that is suffering economically. They have been rewarded with bigger crowds and a positive reaction from their rivals.

“A club can be a channel of communication for aggression, violence and intolerance,” Bellantani told The Guardian. “But it can also be a channel for affection, integration and love.”

Cosenza

It may come as a surprise to hear that Tuscany’s Livorno aren’t the only anti-fascist football club in Italy.

Cosenza, a Serie B club in Calabria, in Italy’s south, boasts devoutly anti-fascist fans.

They have several ultra groups and, while they couldn’t be described as peaceful, not even with each other, they are incredibly passionate in their support for Cosenza and general left-wing anarchy.

The Cosentini see themselves as not just antifa football fans but as the resistance against local corruption and the national discrimination against the poor south of the country.

They even have a self-appointed chaplain in the shape of a rotund 82-year-old football-obsessed Franciscan friar, Padre Fedele, who can be seen in his friar’s gown and Cosenza scarf, leading the singing among a fanatical crowd.

In a time when it may feel that the world has gone irrevocably mad, that the forces of intolerance and greed have triumphed, it’s worth remembering that there are people in every corner of this shabby orb who believe in a better world — or at least that there’s an equaliser on the way.

Next week we sum up the series to date and look at the lessons for the wider left from these football tales about clubs with leftist fans.

Can we find a way of harnessing that passion and intensity to further the cause?

What can we learn from the global success of the St Pauli brand?

Is there scope to get the fans more active in the grit of party political work rather than just declarations of what they are against?

See you then.