This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“WHEN fascism comes to America, it will come wrapped in the flag and waving the cross,” is a quote commonly, if erroneously, attributed to the novelist Sinclair Lewis.

Yet regardless of its provenance, the quote appears eminently applicable to the upheaval taking place across the Atlantic. There, since the murder of George Floyd by a cop in Minneapolis, thousands have been in open revolt against a system whose foundations - not of democracy and liberty but organised violence and white supremacy - have been exposed as they never have been since the 1960s.

Then, as now, there was no middle ground. People were obliged to take a stand on the side of the black and brown victims of racial oppression or on the side of their oppressor, the forces of racism.

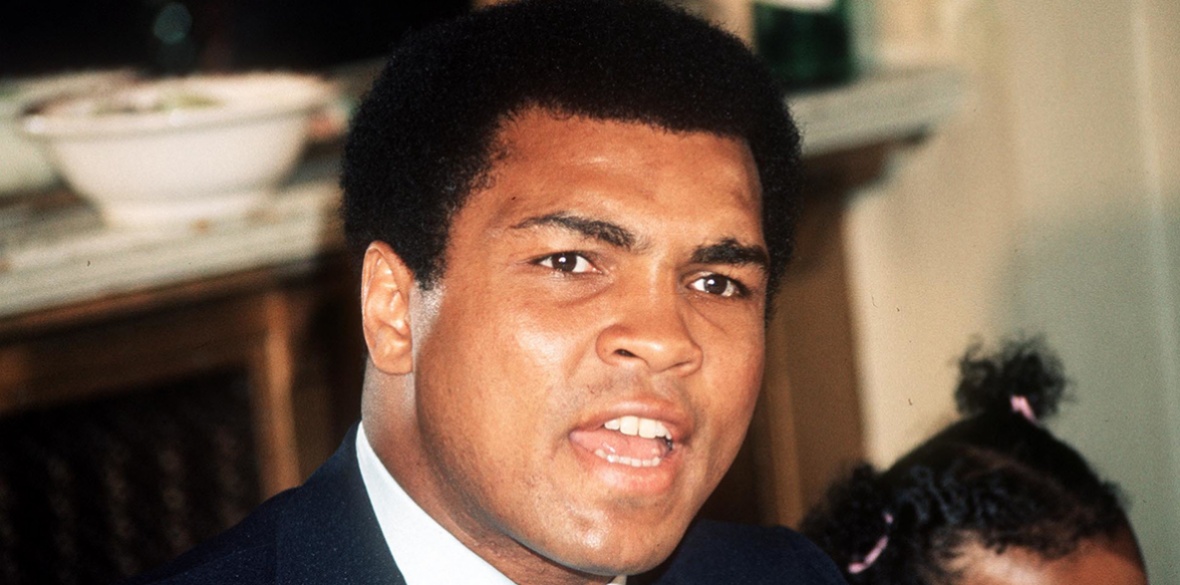

Someone who was in no doubt whose side he was on was Muhammad Ali, a man who fought with courage in the ring and with equal, if not more, courage outside it for the freedom and dignity of his people.

Despite his association with the Nation of Islam, which stood apart from the black civil rights movement and the struggle against Jim Crow in the Deep South – a stance that was central to the schism between the Nation’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm X – Ali reached the point where he could no longer do so.

In 1967, the year the heavyweight champion refused to be drafted for Vietnam and was stripped of his title, he appeared alongside Martin Luther King at a rally for fair housing in his home town of Louisville, Kentucky.

“I came to Louisville,” Ali said, addressing the crown, “because I could not remain silent in Chicago while my own people – many of whom I grew up with, went to school with and some of whom are my blood relatives – were being beaten, stomped and kicked in the streets simply because they want freedom, justice and equality in housing.”

Ali’s relationship with King was far closer than most historians of this period of social convulsion in America have explored. One who’s explored it in depth is Dave Zirin.

In a 2015 piece for The Nation magazine titled Dr Martin Luther King, Muhammad Ali and What Their Secret Friendship Teaches Us Today, Zirin reveals that “Ali and Dr King saw their connection become unbreakable in 1967 when King made the courageous decision, against the wishes of his advisers, to take a stand against President Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam.”

Thus a war raging thousands of miles from America’s shore and the stance both took in opposition to it, no matter the personal cost, brought together in common cause two of the most hated and at the same time loved men in America.

To his eternal credit, King had joined the dots between the war being waged in the name of US imperialism abroad and the war that was being waged against black and brown and poor whites at home. In so doing the Martin Luther King of 1967 was politically unrecognisable from the man who led what Malcolm X derided as “the farce [march] on Washington” in 1963.

In the intervening years he had undergone a transformation and risen to a new level of consciousness.

Though Ali’s defiance of the draft was ostensibly undertaken on religious grounds, it had an earth-shaking political impact across America.

This was not one of the usual white beatniks, intellectuals, students or bohemian hippies commonly associated with anti-Vietnam-war politics at this juncture.

Here was the heavyweight champion of the world, a man revered by poor and working-class blacks in the country’s crumbling inner cities.

Ali’s influence with this demographic was immeasurable and now potentially catastrophic for a military machine and political establishment that was in need of those same working-class blacks to fight their war.

There is no doubt that Ali was influenced by King and King by him. Returning to Dave Zirin: “As the 1960s propelled forward, both men were part of a common black freedom struggle that was blurring the lines between “nationalism” vs. “integrationism” taking on not only the legal barriers to integration set forth by Jim Crow but the intractable racism of the North.

On the same day of their joint appearance together in Louisville, Ali made one of his most famous and powerful political statements to the reporters who were following him as he toured various churches and schools in the city.

Ali: “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No, I am not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slavemasters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end.”

The police brutality suffered by blacks in the ‘60s is being replicated today. What there isn’t today – or at least not yet – are political voices of similar power and consciousness as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and Muhammad Ali.

In the world of sports, the closest thing America has to Ali today is former NFL star Colin Kaepernick, who recently tweeted: “When civility leads to death, revolting is the only logical reaction. The cries for peace will rain down, and when they do, they will land on deaf ears, because your violence has brought this resistance. We have the right to fight back! Rest in Power George Floyd.”

Here an interesting parallel is worth mining. It is that just as the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968 marked a requiem for the concept of non-violence in opposition to racial injustice in his time, so the murder of George Floyd has marked one for non-violence in ours.

The result back then was the militancy of the Black Panther Party and the embrace of black-power militancy with the aim not of being integrated into the system but changing it.

Today we have the Black Lives Matter movement and others taking to the streets with uncommon militancy, determination and anger after years of police brutality.

When it comes to the world of boxing in our time, there is of course no-one close to Ali, not one-top level fighter whom you could even begin to imagine would be willing to sacrifice everything, all their titles and wealth, for a cause greater than self.

No criticism is implied. Ali was more than just a boxer. He was a man imbued with a fierce sense of racial pride and political awareness for whom boxing was in the ‘60s a platform.

How lucky Trump and his acolytes are that this young, audacious, courageous black champion is not around today. As Eldridge Cleaver avowed: “Muhammad Ali is the first ‘free’ black champion ever to confront white America. In the context of boxing, he is a genuine revolutionary, the Fidel Castro of boxing.”

Muhammad Ali was a product of history who in turn became history. His militancy was forged in the crucible of racial injustice and oppression. It is this legacy and this part of his life that liberal America has extended itself in trying to smother beneath the Parkinson’s-ravaged benign monument to the American dream he became in later life.

George Floyd’s brutal murder obliges all thinking people not to let liberal America succeed.

Johns book – This Boxing Game: A Journey In Beautiful Brutality – is now available from all major booksellers.