This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

MUCH of Britain enjoyed explosives this weekend in bonfire night celebrations. If you want to make fireworks at home, you can.

Without any legal hassle, you’ve got the right to use up to 100g of gunpowder which those in the know call “black powder.”

You can either prepare it yourself using a chemistry recipe (there is a wikihow guide), or you can buy it online, for example imported from Germany or China.

To construct good fireworks with colours and effects takes a bit more knowledge, and depending on your taste, a bit more gunpowder.

To store more than 100g of gunpowder legally, you need a pyrotechnics licence, for which you’d need to apply to your local authority.

With fine-tuned designs and attentive construction, fireworks hobbyists can produce stunning displays and pyrotechnic innovations, as well as attracting local admirers eager to lend a hand or simply watch the displays go off.

For the vicarious thrill of amateur fireworks, you can read the discussion boards of the British Pyrotechnics Society without endangering your eyebrows or anyone else’s.

Simpler still is buying ready-made fireworks. Gunpowder was first invented in China, and from there spread around the 13th century through Islamic cultures to European ones.

China still totally dominates fireworks exports: apparently more than 99 per cent of fireworks sold in Britain are made in a single Chinese city, Liuyang.

Until 1847, gunpowder was the explosive used in warfare, weapons and mining, but since then many other explosives have been invented and replaced it.

One feature which made its use dangerous in battle is the thick black smoke that it gives off. In battle, combatants often want to conceal their position.

Once ammunition has been discharged using gunpowder, the position where it was used is given away by the clouds of smoke that hang around in the air.

Suddenly forces using gunpowder go from invisible to visible by firing ammunition. Unlike gunpowder, modern explosives mostly don’t give off smoke.

Since the 19th century, newer explosives like nitroglycerin, nitrocellulose, TNT and gelignite have been developed. The preferred “modern” explosives are C-4 and PETN, which were developed respectively by US-based Phillips Petroleum (which has evolved into oil and gas firm Phillips 66) and German ammunitions firm RWS (now part of Italian firm Beretta).

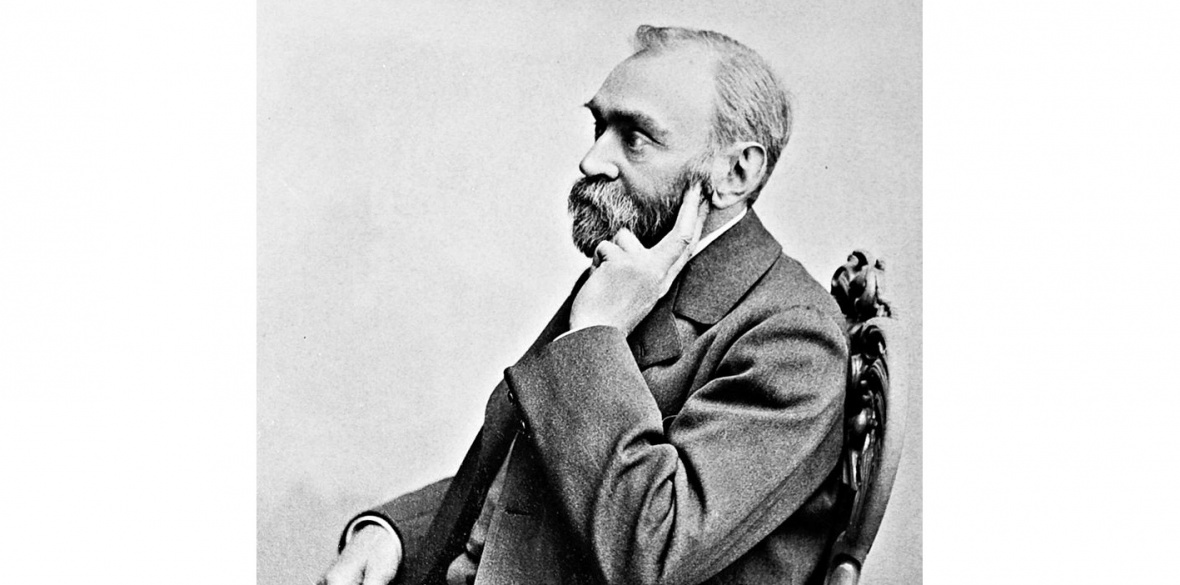

TNT and gelignite were both invented by Alfred Nobel, who made subsequently made a lot of money through the oil mining companies and the arms factories that were the direct consequence of his invention.

Nobel is not best known for his inventions now, though. Conscious that he did not want to go down in history as responsible for his killing inventions, he used his money to endow the Nobel prizes, providing a smokescreen for the story of his life and legacy.

Although most modern munitions are smokeless, deliberately generating a smokescreen can still be a part of warfare.

White phosphorus munitions generate a lot of smoke, thicker and more intense than gunpowder smoke. White phosphorous can be used to create air so thick no-one can see through it.

International humanitarian law restricts the use of white phosphorus: when a person is directly exposed it causes brutal injury, sticking to the skin, reigniting again and again, and is fatal with only a small amount of skin coverage due to its toxicity. That’s what happened when the US used white phosphorous in Fallujah in Iraq in 2004.

It has been widely reported that Israel has dropped white phosphorus on Gaza. White phosphorus is easy to see in photos. Human rights organisations are calling its use in Gaza a war crime, and say that its use contravenes the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Claims and counter-claims about white phosphorus often come in the fog of war, because its use in combat is claimed to be legal as long as its properties as a chemical weapon are unintended.

Other countries also use white phosphorus: for example, during the Syrian civil war, Britain sold white phosphorus to Turkey which was reportedly used for illegal chemical attacks on Kurds.

Israel has signed but not ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention. It has both admitted and denied use of white phosphorous in recent years.

The war in Gaza is visible to most people in Britain only at a distance. Journalists have talked about the difficulty of getting information out of Gaza about what is happening there. The active suppression of information and dissent is part of the offensive.

What is very transparent is the scale of the attack on Gaza.

There have been over 10,000 recorded deaths of civilians in Gaza since the start of the recent attacks. The Israeli military claimed to have dropped around 6,000 bombs in a single week — almost as many as were used by the US in Afghanistan in the whole of 2019.

Where do these weapons come from? Primarily from the US, Germany, Italy and the UK — although exactly what, when and how is not public knowledge.

Market forces are often referred to as the “invisible hand” because control, once turned over to the market, supposedly makes the visible hand – government or rulers – obsolete. But invisibility is a matter of perspective — and a political matter too.

Just as Nobel threw up a vast smokescreen to hide the death caused by gelignite, the agents profiting from arms like to see their place as invisible too, and actively work to hide their involvement.

The Campaign against the Arms Trade (caat.org.uk) has a list of many of the specific companies. Although some of the company names are familiar (BAE systems) other large British arms exporters have less well-known names (Leonardo UK, Raytheon).

These firms prefer to operate as invisibly as possible. Last week activists staged a peaceful picket outside the Elbit Systems Instro Precision factory in Kent, preventing lorries from coming in or out.

They will be protesting at other arms factories this Friday November 10, helping to make the arms trade visible.

You can sign up to join the picket at bit.ly/joinusnov10