This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

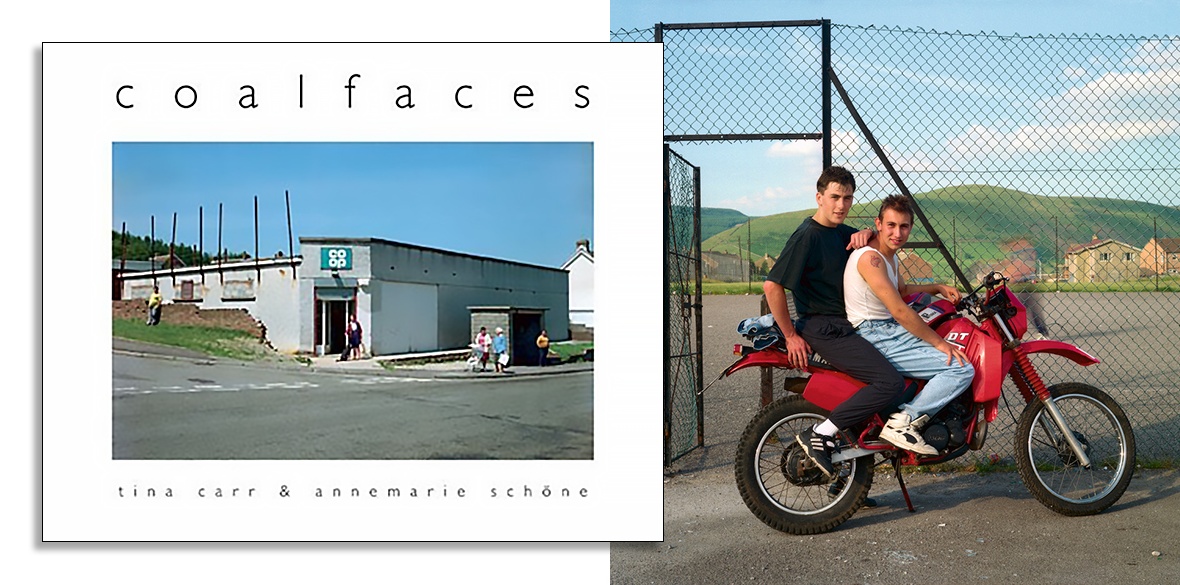

Coalfaces – Life After Coal in the Afan Valley

Tina Carr and Annemarie Schone, Parthian, £25

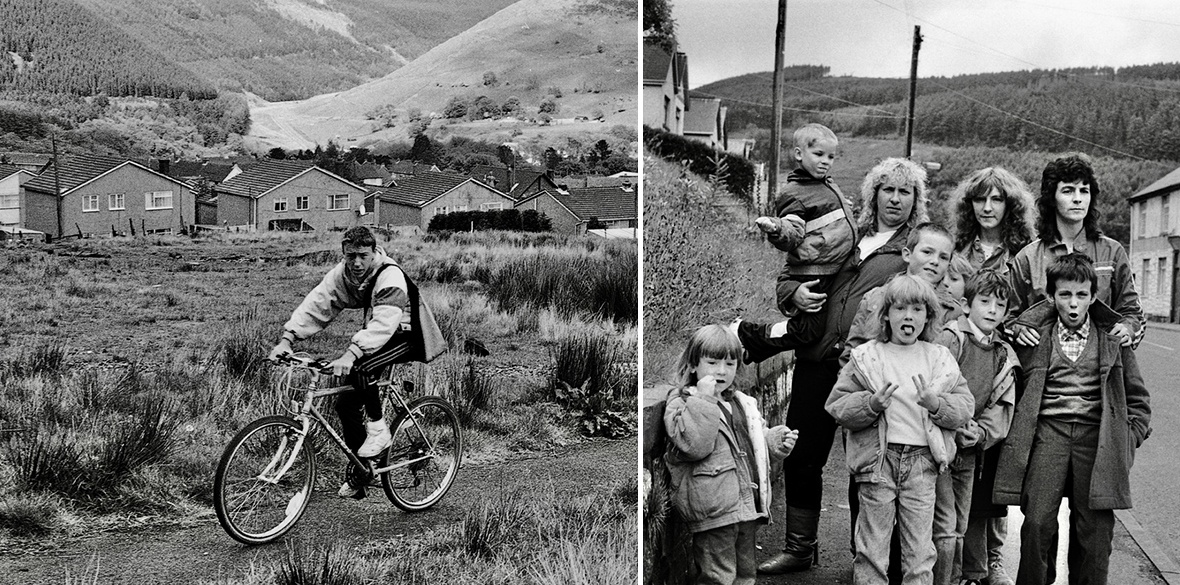

COALFACES portrays the life and landscape of five small communities in the Afan Valley of south Wales, following the closure of the last pit. Since then, the area has had to deal with high levels of unemployment and has faced severe adjustment problems.

Over more than 10 years, Tina Carr and Annemarie Schone worked with the residents of the valley to document the place they call “home.”

As the late painter and broadcaster Osi Rhys Osmond writes in his introduction: “This photographic reportage, together with a DVD of interviews, comes to us with a strange duality.” It presents a challenge but is also a paean to the resilience of the valley people.

“It comes,” he says, “to challenge those who have power over other people’s lives, and to passionately accuse those who dispense that power in such a cavalier fashion. It is, in that sense, an indictment. And it comes, primarily perhaps, to praise those, the subjects of these photographs, who by their persistence, optimism and social energy have constructed a meaningful culture out of tragic and traumatic circumstances.

“Additionally, these images, words and recordings exist to confront those deeply embedded stereotypes of representation that the mining community has traditionally suffered, and to offer documentation as an act of social witness that records and gives voice to a people who usually remain unheard.”

Coalfaces is far removed from the many other photographic volumes that turn the viewer into a passive voyeur. Carr and Schone challenge the reader, demanding a response other than an ooh! and ahh! They don’t simply point their camera as disinterested outsiders at “the natives,” but clearly take the side of the communities they depict, and that have been devastated, neglected and abandoned.

Examining their landscape shots of these former mining communities, you see ribbons of miners’ cottages cast unlovingly in the valley bottoms or on the hillsides, as if dumped there by an alien force in the middle of a lush, unblemished and green landscape of rolling hills. They were indeed dumped there, to be populated by mining families required to dig out the coal from deep below the surface. Despite the poverty and hardship, however, the people forged thriving and lively communities.

A group of boys with chapped faces stare at the camera with truculent expressions; a lollypop lady stands like a fixed road sign in the middle of the street with no traffic and no schoolchildren to shepherd; a Co-op grocery store that looks like an abandoned bunker from the second world war, with only the logo betraying its real purpose, the Cymner Church Hall, first repurposed as the euphemistically named Department of Employment, now like the hulk of an abandoned ship. A pub billiard room with two lone occupants, like extras on a 1950s film set.

This is a world devoid of beauty and of a future, where even the children look old. These images remain seared in one’s conscience — a stark reminder of the devastation wreaked by Thatcher and her acolytes.

Once the last mine had closed in 1969, the inhabitants were left to cope with the consequences with little if any help or support. Overnight, those thriving villages became empty shells, characterised by boarded-up shops and houses, dereliction and hopelessness. Evidence of that industry has also been obliterated.

The authors document this for us with empathy, combined with anger.

The authors quote government policy at the time: the home secretary announced in Parliament the launching of a national community development project to assist communities like these to cope with radical industrial change. The government based its assumptions on the fact that “problems of urban deprivation had their origins in the deviant pathologies of individuals and that these could best be dealt with by better field co-ordination of the personal social services, combined with the mobilisation of self-help and mutual aid in the community.” In other words, the devastation of the mining communities was the miners’ own fault!

The accompanying DVD has face-to-face interviews with people still living in the valleys, who give moving testimony to their lives before and since the pit closures.

As photography expert, Amanda Hopkinson writes in her foreword, Carr and Schone have been inspired by other photographers like Dorothea Lange and her iconic portrayal of the dustbowl US, but also by the pioneering Austrian-born Edith Tudor-Hart, a communist and early documentarist of the harsh lives of south Wales miners during the 1940s.

These photographs, gritty, beautiful, empathetic, sad and humorous, reflect a hardy and feisty attitude, shared by the residents despite the adversity, and they provide us with a much-needed reminder of communities all too easily forgotten about.

Tina Carr and Annemarie Schone are two award-winning artists who have worked together on many diverse projects combining their skills of photography, video and design in innovative, socially committed and environmentally friendly ways.

The Coalfaces project is part of the Valleys exhibition at the National Museum, Cardiff, and runs until November 3. For more information see: museum.wales.