This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THESE days the biggest arguments in many relationships and groups of friends centre on what to watch on telly on Saturday nights. Strictly or no Strictly that is the question. It can be far more divisive than Brexit and more contentious than super gluing yourself to the M25 slip road.

This month I have opted to watch some dancing. Some has been sequins on Strictly but more often with my mate and local beekeeper Abigail.

I visited Abigail’s apiary. That’s the word for a honey production facility from one solitary hive to honey farming on an industrial scale.

She was kind enough to introduce me to her many, many bees – 40,000 in each hive and she has half a dozen – that’s about a quarter of a million bees in all.

Abigail explained the various types of bee from the queen through the drones and the workers and showed me one of the most secret, but wonderful aspects of these insects’ remarkable lives – the waggle dance.

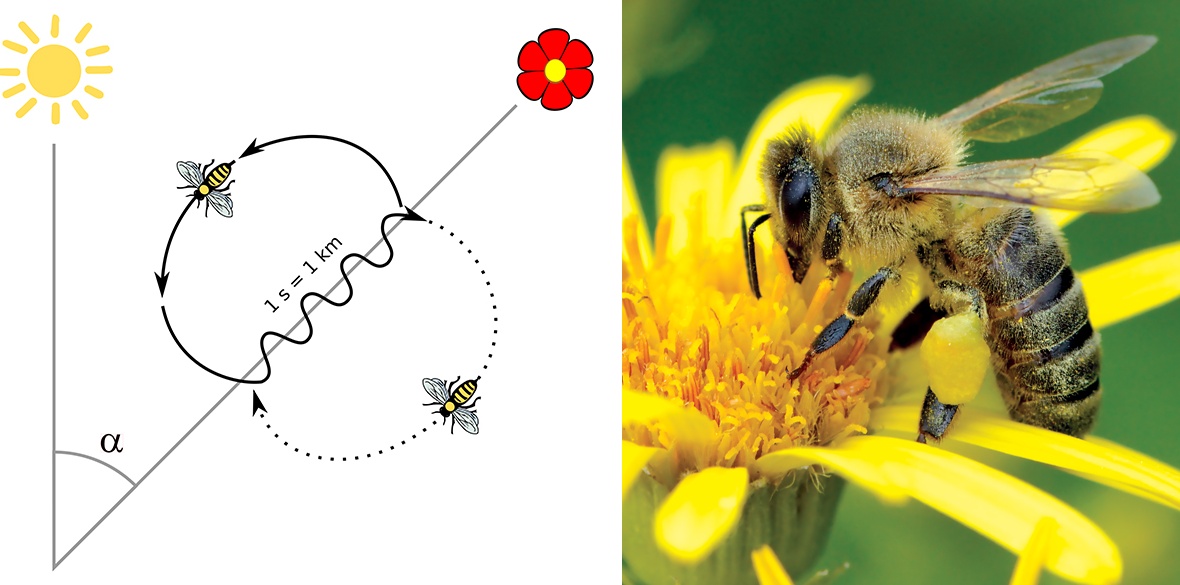

The waggle dance is the method successful worker bee foragers can share information about the direction and distance to patches of flowers yielding nectar and pollen or to drinking water supplies. Even sometimes to a new safe location for a new home. The result of that can be a swarm.

Abigail showed me her bees doing the waggle dance. She also explained some of the subtleties of the dance that is performed on and around the entrance of the hive.

If the location of rich nectar pickings is very near the bee may perform a simple circular dance but if the distance and directions get more complicated the round dance transforms into a complicated figure-of-eight movement – that’s the waggle dance.

Austrian ethnologist Karl von Frisch won a Nobel Prize for his work with honeybees and it was he who first translated the meaning of the waggle dance.

Frisch discovered that bees can recognise compass directions in three different ways: by the sun, by blue sky polarisation, and even at night by the earth's magnetic field.

He also explained what the waggle dance is and why it is important.

Frisch realised bees use the dance to indicate critical information regarding food resources. The dancer bee’s body points in the direction of the food source and the sound produced during the dance indicates how bountiful the food supply is.

Abigail took me to one of her hives to explain the different types of bee. Top of the heap is the queen bee. Each colony usually has only one fertile female, the queen and she lays all the eggs in the hive. Abigail marks her queen with a spot of white paint. You can also recognise the queen by her longer and larger abdomen.

In the spring a productive queen can lay up to 2,000 eggs per day. When her egg output falls the worker bees decide that a new queen is needed. They choose one new larva and feed it on royal jelly alone.

As a result, the larva develops into a sexually mature female bee – the new queen. She is fed only royal jelly for the rest of her life, which can be up to four years.

Next are the drones. They are male bees and their sole purpose is to mate with the queen: they don’t work, don’t make honey and can’t sting.

Since a queen only needs to mate once, most of the drones won't even get the chance to fulfil their role. But worker bees keep a few around, just in case a new queen needs mating. In autumn the worker bees kick the drones out of the hive because keeping them through the winter demands too much work and food.

You can recognise drones because they are stouter and a little bit longer than worker bees. Their eyes are twice the size of worker bees’ eyes because a drone needs good eyesight when it follows the queen high up in the air to mate.

Now we get to the worker bees. All workers are female but are not capable of reproducing. They do all the work in the hive, and they control most of what goes on inside. Their jobs include housekeeping, feeding the queen, drones and larvae, collecting the pollen and nectar, and making the wax. Because they work so hard, during the busy season worker bees live for only about six weeks.

They are shorter and more slender than drones and the queen, and their back legs have special baskets to help them collect pollen. Like the queen, they also have stingers, but they can only sting people and other mammals just once and then they die. They can, however, sting other insects over and over again to protect the hive.

Making honey is an important task for worker bees. They feed it to the developing larvae and also need it as a food source over the winter. All the worker bees in a colony need to work together gathering nectar from flowers and transforming it into honey back in the hive.

In midlife worker bees begin to go out of the hive to collect nectar. They cover a radius of about two miles from the hive and visit 2,500,000 flowers to make 1lb/454g of honey. A single worker bee makes just a tenth of a teaspoon of honey over a lifetime.

Foraging is a difficult and dangerous job for worker bees and, eventually, their bodies wear out. In the open fields, they face huge risks, such as getting chilled or even being gobbled up by birds. They work as long as they can, but most worker bees die while out foraging.

A beehive is one of the cleanest and most sterile natural environments. Worker bees keep it that way to prevent disease. All cells need to be cleaned before they are reused for storing honey or new eggs.

Young worker bees also remove diseased and dead larvae or bees from the hive as quickly as possible, taking them as far away from the hive as they can.

If they sting a large intruder like a mouse to death and it’s too big for them to throw out they will seal the body off with antimicrobial and sticky propolis often called “bee glue.”

Once a worker bee’s sting has developed, she can take on the job of keeping the hive safe. Guard bees position themselves at the hive’s entrance to detect intruders (including bees from other hives), often by smell.

Abigail produces jars of honey, raw honeycomb and beeswax with the help of her quarter of a million female workers.

See also hires out her hives to nearby apple and other fruit orchards at flowering times. A good population of pollinating honeybees can massively increase fruit harvests.

Sadly Abigail’s bees are under threat like so many other pollinating insects in the British countryside. They are under threat from parasites such as the varroa mite.

This is considered by many to be the most serious threat to honey bees. It now occurs nearly worldwide. This external parasite feeds on the blood of adult bees, larvae, and pupae.

The delightfully named Isle of Wight disease (can a disease be delightfully named?) killed many colonies. First found in the Isle of Wight in 1904 it died off in 20 years or so but recurs every now and again.

It was probably the thing that killed off our original native Old British Black honey bee.

Chemicals in agricultural pesticides such as neonicotinoids and organophosphates are acutely toxic to bees and result in many deaths.

Finally bees, like just about everything else, are also suffering from our ongoing climate catastrophe. Our climate is fast approaching one that would support the Africanised honey bee known colloquially as the “killer bee.”

These bees haven’t crossed the Atlantic ocean yet but are moving across both North and South America.

Perhaps that’s good news as these bees can chase a person a quarter of a mile (400m). They have killed some 1,000 humans, with victims receiving 10 times more stings than from European honey bees.

Any one of these threats alone could cause decline to bee populations, but when combined together, they could cause an end to delicious honey from Abigail and her bees.

WWI Poet Rupert Brooke remembered his Cambridgeshire home when in Berlin in 1912 and asked the well remembered question “...and is there honey still for tea?”

Yes there is Rupert, but who knows for just how long.