This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE Andes rise high above the Atacama desert on the western coast of South America, higher in fact than a model based on basic plate tectonics would indicate. Their height is part of why the Atacama desert is so dry.

Unlike in Britain, where the west coast is wetter than the east, the prevailing winds from the oceans around southern South America come from the Atlantic, rather than the Pacific. These winds were called the “trade winds” by European nations who used them in their imperial and colonial expansions.

Just like on the island of Britain, but switching east for west, the prevailing winds pick up water over the ocean, and on hitting the mountains rise, cool and squeeze out their water load into rain clouds that keep the east coast of southern South America lush and fertile.

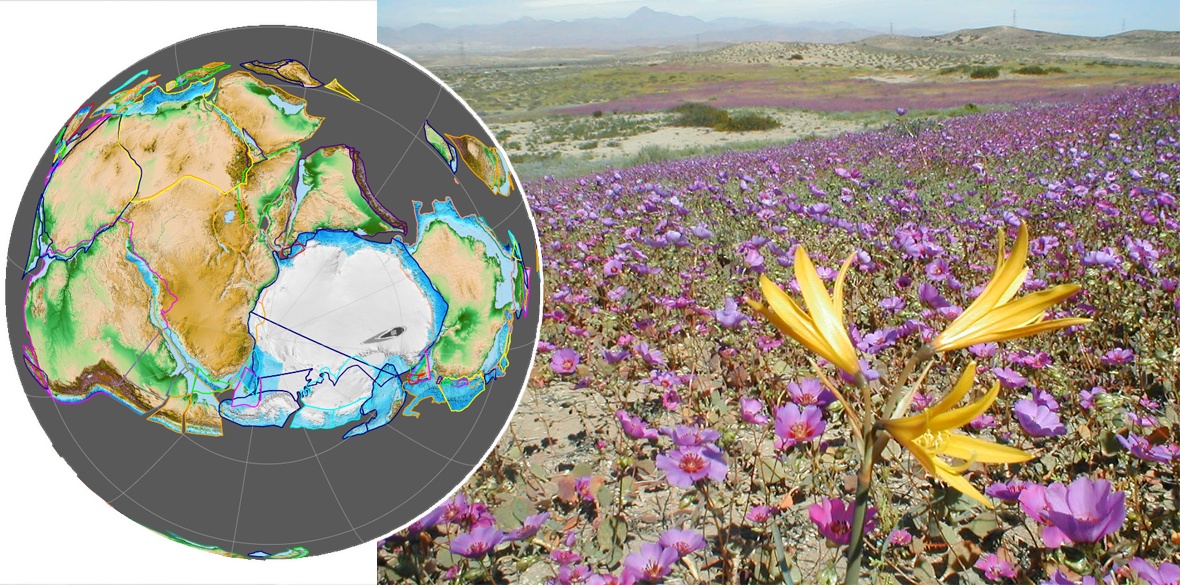

The dried-out air passes over the very peaks of the Andes to the other side, where it warms and reabsorbs any remaining moisture. Thanks to this the Atacama desert has a claim (along with the poles) to being the driest place on Earth.

Some Atacama weather stations have never recorded any rain. It’s due to these incredible clear skies that one of the most important international space telescopes was constructed high in the desert.

The Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA) Radio Telescope is one of the world’s most valuable scientific instruments to learn more about the universe, as we wrote about in our last column on the geopolitics of big-budget science.

The scientific richness of the Atacama desert does not end with looking up at the heavens. It is full of desert plants and bacteria that are well suited to living in the hot dry conditions of the desert.

Last month a major study of the genetics underlying the Atacama’s flourishing plantlife analysed their shared adaptations to heat and drought.

The researchers hope that understanding this will allow for the development of new crops to feed people who live in places where climate change is endangering their food supply.

The bleakness of this prospect is matched only by the determination of those people who are working for the improvement of the lives of themselves and their neighbours.

The area of the Atacama was not always a desert. In the deep past, the landmass of South America was locked together with Antarctica, and the pieces of land that would become Africa, Australia and parts of Asia in the supercontinent of Gondwanaland.

In those times, the climate and ecology of those areas was of course unrecognisable. Over hundreds of millions of years the continental drift pulled South America apart from its closest related rock formations in Antarctica.

The history of this connection can be found in the fossils of related dinosaurs found locked in the rocks of both places.

This month, the analysis of a unique dinosaur was announced from a fossil on the very tip of the continent, south of the Atacama.

The dinosaur, Stegourus elengassen, had pairs of flattened bones splayed out sideways along its tail, unlike any other known clade of dinosaurs.

The researchers would like these to be known as “macuahuitl:” the word for a blade-like war club used by Aztec fighters.

It is believed it represents a distantly related group of dinosaur species that diverged from Stegosaurus very early on. Unlike the larger Stegosaurus, this dinosaur was 1 metre tall and 2 metres long. The work is particularly exciting to palaeontologists.

Understanding the diversification of creatures like this both before and after the break-up of Gondwanaland tells them more about the conditions of the continent and dinosaur adaptation more generally. Also, presumably because dinosaurs are fun.

Just 12,000 years ago, tens of millions of years after the last Stegourus roamed the Earth, the Atacama was still grassland. Something mysterious happened at that moment, alongside the last major climate upheaval that ended the last ice age, the extinction of large mammals from the region, and the movement of humans into the area.

This event left 75 kilometres of the region thickly covered in lumps and slabs of twisted black and dark green glass. This extremely striking phenomenon has been given a new explanation according to a paper published last month.

These researchers analysed the crystals inside the glass and found evidence that they were extraterrestrial. They suggest that a large comet exploded above the surface of the Atacama, and that fireballs hotter than 1,650°C blasted the sandy soil into hot molten glass over a period of a few hours.

The liquid glass flowed into strange twisted shapes, and preserved the prints of grasses onto which it poured into the future. The authors suggest that the enormous explosions might even have been seen by humans who were moving into the region about that time.

The geographic descendants of these people moved into the area permanently. These peoples successfully repelled the colonial advances of the Incas, and after the brutal colonisation by Spanish forces, fought and won Chilean independence in 1818.

The Chilean people in recent times have produced the historic Salvador Allende administration and have survived the criminal opposition to it, and the subsequent horrors of the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship.

This week the Chilean people have elected by a phenomenal democratic movement a new president, the leftist Gabriel Boric. Chileans were joined in celebration across the world by people who believe that Boric’s socialist agenda will be a hopeful new era for politics in the rich and historic culture and lands of Chile.

The Andes are the oldest mountains in the world: older than the dinosaurs, older than the comet-glass and the sturdy desert plants.

They are higher than the simplistic models of plate tectonics would predict, and recent research tries to understand this in terms of subduction (sinking under) of the easternmost side of the Pacific plate that runs along the coast of Chile, and the movement south of the Juan Fernandez Ridge.

In fact, they still seem to be getting taller. The mountains and the people of Chile continue to rise up, and theories can only be constructed to follow them.