This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IT IS 10 years this September since Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, bringing global capitalism to the point of collapse.

Although a total meltdown was avoided, the crash triggered a slump of 1930s proportions, and for most economies the last decade has been a lost decade of low growth, low investment, low productivity, debt, deficit, with virtually no improvement in real incomes for the 90 per cent.

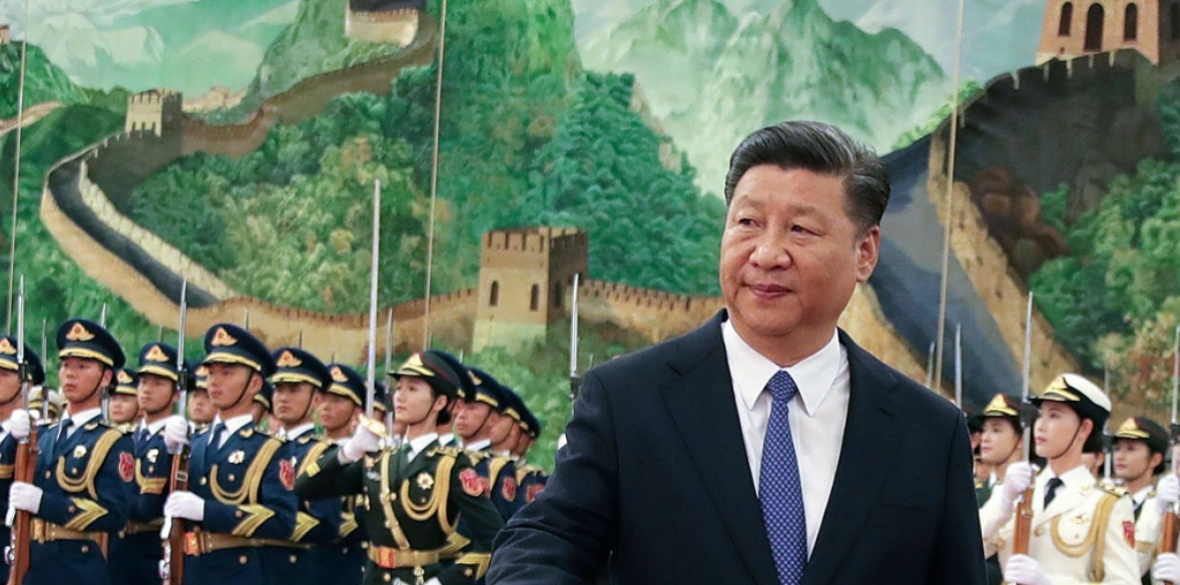

The stand-out story of the period has to be the continuing rise of China. Initially also badly hit by the crisis, China recovered rapidly to emerge today as a major economic power, moving steadily closer centre stage in the global order.

Since 2009, the Chinese economy has nearly tripled from $4,600 billion to over $12,000bn in 2017.

Growth at 9-10 per cent a year was rapid up to 2011, then settled at a more sustainable 6-7 per cent a year, still well above the world rate at 3.9 per cent.

Per capita income has risen from $3,500 (£2,700) in 2009 to $6,790 in 2017, between 10-15 per cent a year, putting China on course to reach a high-income level in eight years’ time.

Some 15 million people a year have moved to cities; eight to 10 million jobs are created annually. In 2017, there were 11 million new jobs compared to India’s one million.

As is well known, since 1978, China has lifted some 800 million people out of poverty. Since 2012, extreme poverty has continued to fall from 100 million to 30 million, heading towards complete elimination in three years.

The five-year plan (2011-15) stipulated minimum wage rises of 13 per cent a year. Together with the fall in poverty, this is helping to improve income distribution and reduce inequality.

In the last few years, China has begun to shift from reliance on low-cost export manufacturing and investment, rebalancing the economy towards domestic consumption and high-tech levels.

This bold transition, moving the very basis of the economy towards new patterns and pillars of growth, is now well under way.

Trade has fallen from 37 per cent of GDP in 2008 to 20 per cent currently, while consumption has risen steadily every year since 2012.

Now China’s 400 million middle-income consumers are a major force in driving the world economy.

Between 2011 and 2017, traditional economic sectors — coal, iron, steel, cement — fell from 75 to 60 per cent of the economy, with energy, technology, healthcare and entertainment sectors becoming new growth drivers. Service sector employment has risen from 33 to 45 per cent.

Government investment is expanding public infrastructure: the high-speed rail network exceeds 13,600 miles, about two-thirds of the world’s high-speed railtrack in commercial service, reducing travel times across the country from days to hours. Electricity generation continues to increase annually by over 10 per cent after 2008.

Labour productivity has risen 9.6 per cent a year since 2003. Today China has 109 companies in the Fortune Global 500, up from around 30 in 2008, and 10 in 2001.

Chinese industries such as electronics, machinery, automobiles, high-speed railways and aviation are advancing to the technological frontier, if not already driving innovations in new sectors including AI, autonomous vehicles, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, advanced energy storage and quantum computing.

China is now challenging Western monopoly in robotics and 3D printing. Spending on R&D will soon overtake that of the US.

China is striking out into the new era of clean power, mobilising more than $100 billion annually for renewable energy technologies.

By 2017, China had more than a third of the world’s wind power capacity, a quarter of its solar power, six of the top 10 solar panel makers and four of the top 10 wind turbine makers. It sold more battery-only cars last year than the rest of the world combined.

Public social spending rose from 6 to 9 per cent of GDP between 2007 and 2012. The healthcare spend since 2009 totalled $480bn; 95 per cent of the population has been given basic health insurance, gradually extending to cover all critical illnesses.

Life expectancy rose from below 75 years in 2010 to 76.7 years in 2017. A minimum income standard is in place for all, and a growing number of companies are enrolling their workers in government programmes that grant industrial injury benefits, maternity leave and unemployment benefits.

Pension coverage has leapt ahead: the proportion of those enrolled in a pension almost doubled between 2009 and 2012; now around 60 per cent of those aged 60-plus get a monthly pension.

The media, despite government controls, has more diversified content, TV channels air current affairs discussions and investigative journalism is developing a certain critical edge.

The film industry, which 10 years ago was swamped by fake DVDs, is experiencing a renaissance, with box office revenues close to overtaking those of the US.

On the international front, since 2008, China’s growth has accounted for between 30-50 per cent of world growth, well exceeding the US at less than 20 per cent, so playing a major role, scarcely acknowledged by the West, in mitigating global recession.

It has become a major trading partner of over 120 countries, now vying with the US as top trading nation. It is a major driver of growth in the developing world: by 2011, its development banks were lending more than the World Bank. The Belt and Road Initiative, launched in 2013 to build regional connectivity across Eurasia, has 52 countries signed up so far and 1,700 projects are under way.

China is step by step making its mark on global finance with the establishment of the Brics Bank (2013), the Silk Road Fund (2014) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (2015). The list could go on.

It is certainly not intended to deny the many shortcomings, and the costs, of China’s advance — it is still a developing country.

Looking to the future, the aim is to improve the quality not just increase the quantity of growth. However China clearly has come a long way in a very short time.

Now the charges from the US anti-China lobby that China’s advances are a result of “cheating” appear as they are, entirely cynical.

It is not just a question of the challenge of a rising power: China’s advance, in contrast to the West’s sluggish performance, dramatically exposes the difference between a system which chooses to bail out the banks and one which bailed out the economy; between one that does all it can to boost its financial sector, and one which promoted economic stimulus to boost production; between one which squeezes the poorer in the blind pursuit of profit and one which raises up the poor, organising development in a systematic way; between one that pumps out huge amounts of speculative “hot money” into the world economy to play havoc with other countries’ financial systems and one that offers patient capital to help others manage their financial difficulties so as to avoid crises; and between one that permits private interests to run rampant and one that maintains the predominance of public ownership.

Over the last decade, while Western economies have poured their “printed” money round and round the ether of financial markets in the same exhausted circles, China has become a different country and indeed the world is becoming a different place.

The moment that China overtakes the US as the world’s largest economy, probably sometime before 2030, will mark the psychological turning point of the 21st century.