This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IN THIS season of goodwill and family get-togethers I am going to introduce you to my Uncle Bert. Sadly Bert died in 2012 but I will always remember him and the stories he told me about his exciting life.

Bert met my mum’s sister Phill at the legendary Hammersmith Palais. They were both competition-winning ballroom dancers. He married Phill and became my uncle.

When I started to get interested in left-wing politics in my teens, Bert could always be relied on to take my side in family discussions. He was a solid working-class hero and a staunch trade unionist till the day he died. He abhorred wars and hated bosses, indeed any kind of authority.

He left school at 14 and took up the somewhat dangerous trade of roofing. When war came he was conscripted into the Royal Navy as an ASDIC operator working an early form of radar.

Bert, who always called me “Nipper,” would show me his Arctic Star — the medal he won on the Russian convoys and laughing tell me of his visits to the Soviet Arctic ports “where a packet of English fags could get you anything at all.”

One reason I have been thinking about Bert this Christmas is that December marked the 75th anniversary of the Bevin Boys — and Uncle Bert was one of them.

Bevin Boys were young men conscripted to serve in Britain’s coal mines between 1943 and 1948. Their story is one of real working-class heroism.

Seventy-five years ago as the war raged in Europe the cold snowy winter was causing a major crisis at home. Most young miners had gone to fight in Europe and coal production had fallen to an all time low. By early December it seemed that coal stocks would be completely exhausted by Christmas.

On December 2 1943, Ernest Bevin, the minister of labour and national service in Winston Churchill’s wartime coalition government, announced in the House of Commons a scheme that was to change the lives of many young men.

They would be directed to work underground in the mines. It was nothing less than forced labour and introduced by a Labour politician, albeit a right-wing one serving in Tory prime minister Winston Churchill’s Cabinet.

Since war had been declared against Germany in September 1939, a large number of experienced miners had been called up into the forces.

Desperate measures to get more men down the pits included the release of ex-miners serving in the Home Forces; the recall of retired miners; recruiting among the unemployed; even trying to employ young boys of school age was tried with little or no success.

Rightwinger Ernest Bevin, previously leader of the Transport and General Workers Union, decided the only way of overcoming this situation was to conscript an additional 50,000 men, forcing them to work underground in the coalmines over a period of 18 months.

The system devised by Bevin was a ballot whereby young men between the ages of 18 and 25 years who qualified for national service would be selected according to the last digit of their registration numbers.

The first numbers were drawn in the minister’s office on December 14 1943. A new batch would be drawn every two weeks from then on. Uncle Bert’s number would come up two or three years into the scheme.

I never understood why Bert had been conscripted twice, first into the navy and then, after being demobbed from the senior service he was again called up to serve down the mines, but sadly it is too late to ask him now.

Always fiercely independent, my Uncle Bert really resented what he rightly considered to be forced labour but he knew only too well that any refusal to go down the pits would result in at least an unaffordable heavy fine and more likely a jail sentence under the Emergency Powers Act.

Bert once told me that some people believed that some Bevin Boys were conscientious objectors but from what I have learned since that wasn’t the case.

After a medical examination Bert reported to the government training centre at the pit where he would work.

Bert didn’t tell me which colliery he worked at but we know that Bevin Boys worked in pits over England, Wales and Scotland.

He was paid £3.50 a week and he lived in an army camp-style miners’ hostel for which a rent of £1.25 a week was docked from his weekly pay packet.

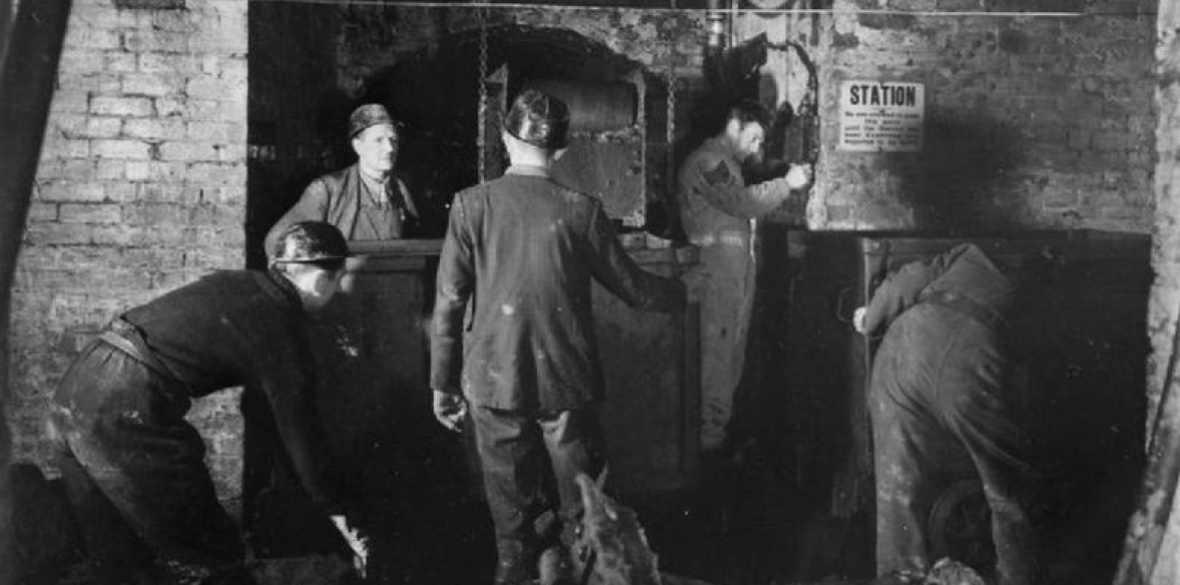

Equipped with a miner’s helmet, overalls and a pair of steel-capped boots, Bert, like every other miner, carried a heavy safety lamp, a snap tin containing sandwiches and a water bottle.

The safety lamp would be issued on production of a brass check. This was followed by a rigorous search to make sure that neither Bert nor his mates were smuggling tobacco, cigarettes or matches for a secret smoke down below.

Bert told me how terrifying his first drop in the cage was, and he never really got used to it.

“It was so fast,” he recalled, “and the pressure in my ears was very painful and sometimes it even caused nose bleeds.”

Once the cage had dropped him anything up to a mile straight down into the Earth’s core, there was a long walk over rough and rocky ground to finally arrive at the coal seam where he worked in dangerous and cramped conditions.

Bert never worried about how hard the work was but remembered “the appalling conditions with no toilet. It was sometimes hot, cold, wet, draughty, dusty, dirty but it always smelled bloody awful.

“The constant noise of machinery was deafening and dangers and risks were too numerous to mention. We all worried about explosions, fire or roof falls.”

At the end of the long shift Bert would rush back to pit bottom to join the queue to get back into the fresh air, civilisation and the always inadequate pit head baths.

Bevin Boys received no form of recognition or reward for their heroic services to the war and post-war effort in which they played such a vital part.

It was not until 50 years later that a handful of them decided to form the Bevin Boys Association in 1989.

They fought for recognition for what they had contributed in both war and post-war peace.

It wasn’t until 2013 that an official memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire was unveiled. It was too late for uncle Bert — he had died a year before.

But at last there was a memorial that paid tribute to him and his 48,000 Bevin Boy comrades who had kept the home fires burning both in war and in the hard austerity years that came with peace.