This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

WHITE is the colour of evil in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The horror is ivory. The coveted material fires the greed and stokes the chaos of the entire sprawling colonial project depicted in the novella. The lust for tusks has overtaken the Africans and their European colonisers.

The tale’s narrator, Charles Marlow, is hired on as a steamboat captain by a Belgian ivory trading company. At the farthest upriver outpost, he will encounter Kurtz, gone rogue but still claimed by company executives and agents in the field to be their most successful ivory producer.

On the journey inland, Marlow’s boat stops at the company’s central station. There he sees “men strolling aimlessly about in the sunshine of the yard. The word ‘ivory’ rang in the air, was whispered, was sighed. You would think they were praying to it. A taint of imbecile rapacity blew through it all, like a whiff from some corpse.”

Kurtz dies on the way back downriver and at the close of the book, Marlow attends his funeral back in Europe. There he meets the dead man’s cousin, an organist who tells Marlow that the multitalented Kurtz had been “essentially a great musician” and could have had a triumphant career. Marlow doesn’t doubt these claims.

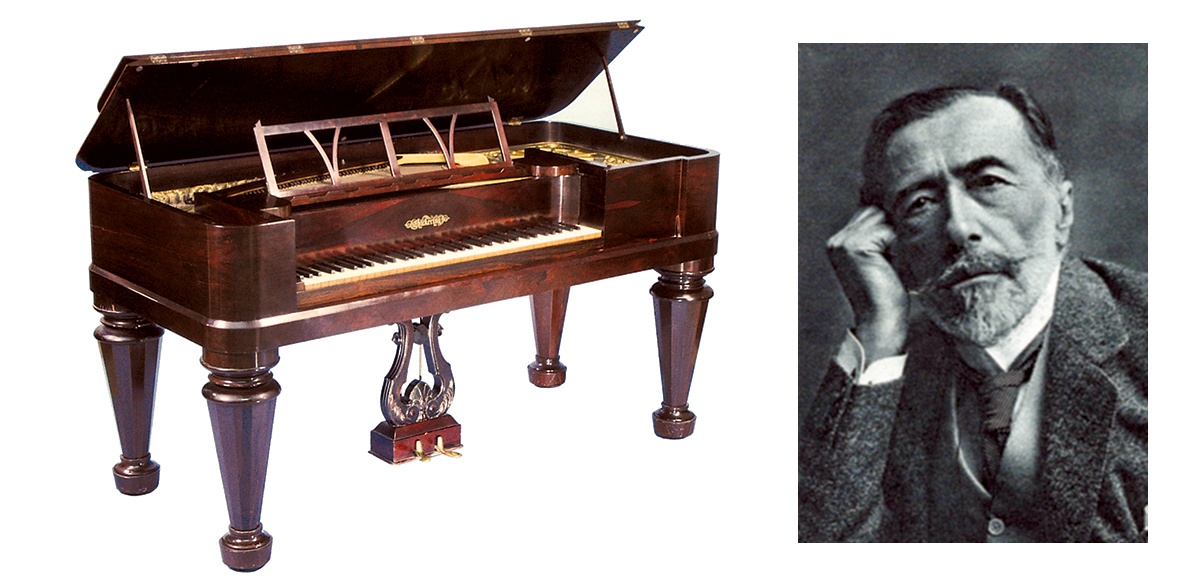

In his tale’s closing scene, Marlow visits the dead man’s fiancee, curious to meet the woman loved by the mad genius of the jungle. Marlow has with him Kurtz’s letters and a photograph of the woman and gives these effects to her at her mansion: “A grand piano stood massively in a corner, with dark gleams on the flat surfaces like a somber and polished sarcophagus.”

Kurtz must have been a pianist.

His piano described by Marlow would have been veneered either in ebony or rosewood, both colonial commodities plundered from Africa. Looming in this darkened fortress of wealth and “civilisation” is a musical coffin, as silent as the grave. Like Kurtz, the tusks are now in their final resting place.

Marlow doesn’t mention the white ivory keys of the piano he spies but the visitor knows the ivory is there and so do we, corruption and exploitation transformed into a furnishing, a piano — that domestic symbol of European culture and refinement.

The ivory must be touched if the piano is to sing. Conrad makes no acknowledgment in Heart of Darkness that the precious material comes from living beings.

As young pianists playing old pianos, we are taught that ivory is warm and welcoming to the touch. The player’s skin does sense that the white key tops came from living things, but that truth isn’t allowed to penetrate into the psyche, to travel from the hand to the conscience. But what if musicians young and old were played recordings of the horrifying distress of elephants when beset by poachers.

Elephants scream when they are shot, the survivors cry when they mourn.

Who would get pleasure out of playing Chopin on keys made of human bones?

Steinway began using plastic keys on their instruments in 1958. With an international ban on the ivory trade in effect since 1989, various other materials are now used as a substitute.

Conrad published Heart of Darkness in 1899, 14 years after Belgium had established the cynically named Congo Free State in 1885, annexing the territory as a colony in 1908. This vicious regime coincided with the high point of global trade in ivory used for combs, doorknobs, billiard balls, and pianos — all luxury items.

Ivory legislation has become stricter in recent years. Britain passed a total ban on its sale in 2018 and it into effect last year. Though unnamed, the piano makes for the first of the law’s exceptions: “musical instruments made before 1975 with less than 20 per cent ivory by volume.” A dozen US states have similar bans, though that in New Jersey is absolute: no sale of ivory whatever. Heirs can inherit an old piano, but they can’t sell it. The legislation will have a downward effect on prices of old pianos, making them worthless for resale.

Pianos are no longer the entertainment center of the middle-class home.

It is fittingly ironic that New Jersey should have passed the strictest of the ivory laws, since Atlantic City had hosted the notorious Bonfire of Square Pianos of May 24 1904.

Attendees of that year’s National Association of Piano Dealers convention made a mountain out of square pianos — by one exaggerated tally, 1,000 of them.

On that spring evening on the Jersey shore, the conventioneers danced around the blaze waving red lights. The event was reported around the world.

One luxuriously appointed square piano was painted pale with darker letters delivering a mocking epitaph: “I’ll feed the flames by the salt sea air.” It was dubbed “The White Elephant.”

This is an abridged version of an article that first appeared in counterpunch.org. DAVID YEARSLEY is a long-time contributor to CounterPunch and the Anderson Valley Advertiser. His latest book is Sex, Death, and Minuets: Anna Magdalena Bach and Her Musical Notebooks. He can be reached at [email protected]