This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

ALAIN BADIOU, in his book Petrograd, Shangai: Les Deux Revolutions du XXe Siecle (the two revolutions of the 20th century), describes the revolutionary impact of the Cultural Revolution on his generation as follows: “Every subjective and practical trajectory has found its nomination in the tireless creativity of the Chinese Revolution.”

The Cultural Revolution was a creative project of engaging new militants to the revolutionary ideological struggle. Mao conceived the Cultural Revolution as a “struggle“ against an objective reality, the danger of deradicalisation that every revolution faces.

The Cultural Revolution, so to speak, emerged as a forced creativity. The harsh reality that the desired society could not be achieved immediately after a socialist revolution, the paradoxical nature and unique challenges and responsibilities of continuing this struggle from a state position were being learned by experience, and the leaders of the Chinese revolution had no ready-made prescription, neither from theory nor from experience.

Mao found the solution in what he described as the mobilisation of the masses, the project of giving students and workers a great sense of mission and making them new leaders of struggle against the old cadres of the revolution who had lost their radicalism and their capacity for struggle. But the Cultural Revolution, one of the most creative projects in the history of revolutions, failed because it resorted to a mode of ideological and political struggle that neglected the logic of state governance in the conditions where the logic of state and economic management was still required.

The Cultural Revolution ended, but the creativity of the Chinese Revolution, of the CCP, did not end. Since then, the CCP has continued to search for ways to struggle for a path to socialism from a state position and, with the Deng Xiaoping and Xi Jinping eras, has undertaken other projects that are among the most creative in the history of socialist experiments.

Starting from the premise that the goal of Chinese socialism is first and foremost the development of the productive forces and the reduction of poverty, Deng resorted to the market model, which he considered to be the most effective model for developing the productive forces, and invented the formula of “market socialism.” During this period, revolutionary ideological struggle was relegated to the second plan. Deng’s attempt to solve problems that could not be solved by ideology through economic means, as in the NEP period in the USSR, was understandable, but it also led to the danger of ideological regression and left unsolved problems that could not be solved by economic development.

The Deng period created the perception in the world revolutionary movement, and in capitalist forces, that the CCP was going down the capitalist road.

The question has rightly been asked: if the intention in resorting to the market model is only to achieve technological and economic development, what measures will set the stage for this path to end in socialism rather than capitalism? These questions, at least for outside observers, have remained largely unanswered.

The refusal of Marxists in general to accept this period in China as an experience of socialism is quite understandable, although there is much evidence to suggest that what the market socialism project meant for Deng was a sincere and creative experiment in solving the economic problems of the transition to socialism, rather than a cover for the transition to capitalism. Indeed, even Marxists who closely follow the CCP who are very critical of Deng and its aftermath, such as Maurice Meisner, have noted that there is hardly any data to suggest that the CCP is not sincere in its project of market socialism.

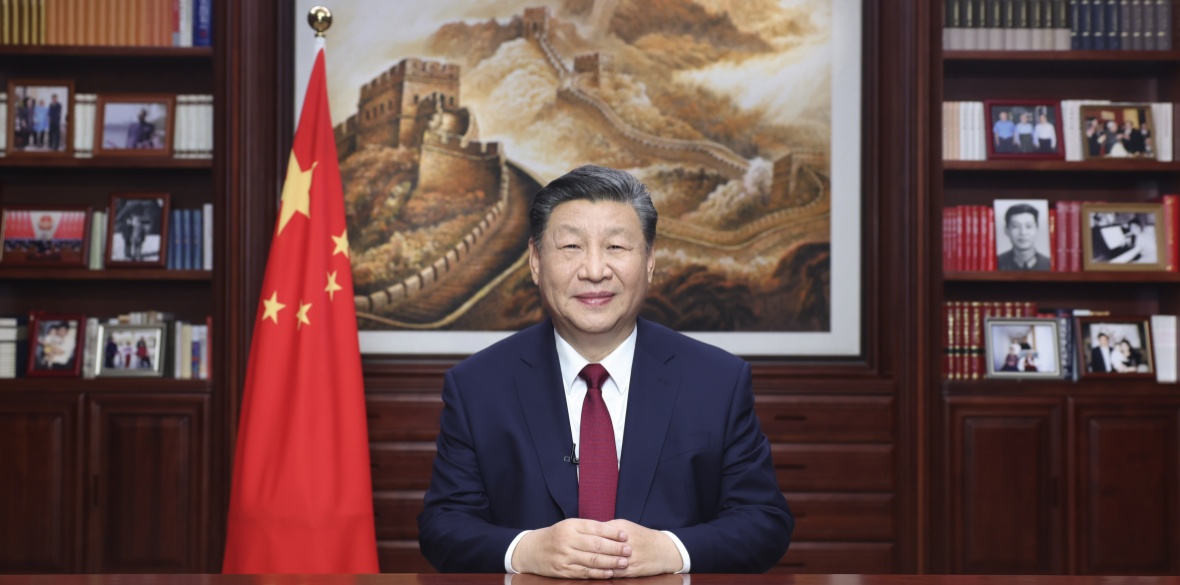

With the Xi era, we are witnessing the return of political and ideological struggle. But this time, compared to Mao’s Cultural Revolution, it is a struggle that recognises more the logic of state and economic management. In this most recent creative phase of the Chinese Revolution, ideological and political struggle and the market model are being developed side by side without cancelling each other out. This is what led Korkut Boratav, the pre-eminent Turkish Marxist economist, who follows China closely, to ask: “Is Xi a Mao-Deng synthesis?”

Xi stands out for his high personal interest in Marxism and his theoretical studies, for his faith-building political speeches with constant references to Marxism and communism, and for his ideological campaigns and educational programmes that encourage the study and discussion of Marxism throughout the country.

Xi has repeatedly urged party members to remember that the ultimate goal is communism, calling them to the mission. By recalling the ideological and political struggle and resorting to egalitarian practices, Xi has managed to attract the attention of Marxists who had lost interest in China. However, this attention is cautious and questioning, or perhaps more accurately ambivalent, given the continuation of the formula of market socialism.

Many observers see themselves faced with a tension or incompatibility between a capitalist infrastructure and a socialist superstructure, which does not conform to their Marxist model of infrastructure-superstructure harmony: in one hand ongoing capitalist market relations, exploitation of the working class and a capitalist consumerist culture; in the other hand stronger emphasis on Marxism, ideological commitment and equality, as well as some concrete steps such as fight against corruption, strict control over capitalists and total eradication of absolute poverty.

The “incompatibility of the infrastructure and the superstructure” is preventing Marxist observers from taking a clear position. They ask: “But does a socialist political and ideological structure really mean anything, if what is decisive are the relations of production according to Marxism?”

This question can be fairly answered only by recognising the facts that the establishment of socialism does not begin and end with the moment of revolution.

In the post-revolutionary processes there are still economic and social objective conditions that impose themselves on the revolutionary party in power, conditions that force the leadership to take some necessary steps bearing favourable as well as unfavourable consequences in terms of a communist project.

The distance between the objective conditions of the current moment and the goal to be achieved requires a state of ideological subjectivity that will prevent surrender to the objective conditions of the current moment and a political organisation with the capacity for intervention and struggle.

In this respect, the political and ideological structures of societies in transition should be seen neither as forces that can shape the mode of production as they wish, nor as established superstructures in harmony with the mode of production, but as ideological and political centres that carry out a struggle towards a goal and in spite of the objective conditions, at the same time taking into account the requirements of these objective conditions.

Today, there is a superstructure in China which is organised according to the logic of ideological and political struggle, which is struggling for the goal of socialism within the objective conditions. It is the existence of a struggle and its direction that determines the nature of the current Chinese experience. Struggle is by definition possible at a point back from the goal; it owes its existence to the tension between its present and its future.

The ideological struggle of the Xi era is waged by deliberately avoiding pushing the limits of state governance and economic management. In the Xi era, unlike the Cultural Revolution, ideological struggle is not seen as a field that will complete social transformation.

For Xi, the revolution at the level of productive forces and relations of production is not complete; the need for a centralised political power to manage the complex relationship between productive forces and relations of production is not past its sell-by date.

This difference in perspective leads Xi to position the ideological struggle as the construction of political subjects who recognise the economic and political objective realities of the current period, but who do not surrender to these objective realities and lose the horizon of transformation.

The level of dedication, sense of mission and dynamism generated in this period must surely be very weak compared to the aura of “creative absolutism” of the Cultural Revolution, since the ideological struggle is now conceived within the confines of the state and the economy.

Xi prefers a weak but controlled ideological struggle rather than a strong ideological dynamism that eventually evaporates due to its lack of a concrete and positive political programme and to its negligence of objective conditions.

We cannot know in advance if this controlled ideological struggle will carry China forward to communism, or if it will drown in negative and restraining objective conditions and turn into an official and lifeless bureaucratic Marxism; however, in terms of the current moment, we can say that Xi’s ideological struggle serves as a progressive vector in terms of resisting the objective conditions surrounding the CCP.