This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THERE is widespread ignorance on the left about what is called civil resistance — non-violent struggle.

Let’s start with first principles. In her essential 2021 book Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs To Know, Harvard University’s Professor Erica Chenoweth defines civil resistance as “a method of active conflict in which unarmed people use a variety of co-ordinated, non-institutional methods — strikes, protests, demonstrations, boycotts, alternative institution-building, and many other tactics — to promote change without harming or threatening to harm an opponent.”

Following the October 7 terror attacks by Hamas, various people told me on X/Twitter that this method of struggle is unrealistic, ineffective, not as powerful as armed resistance, relies the on inherent restraint of the oppressor, can only create gradual change, and so on.

On October 8, the popular leftist X/Twitter account @zeisquirrel approvingly posted a video of Malcolm X asserting: “You don't get freedom peacefully. Anyone who is depriving you of freedom isn’t deserving of a peaceful approach.”

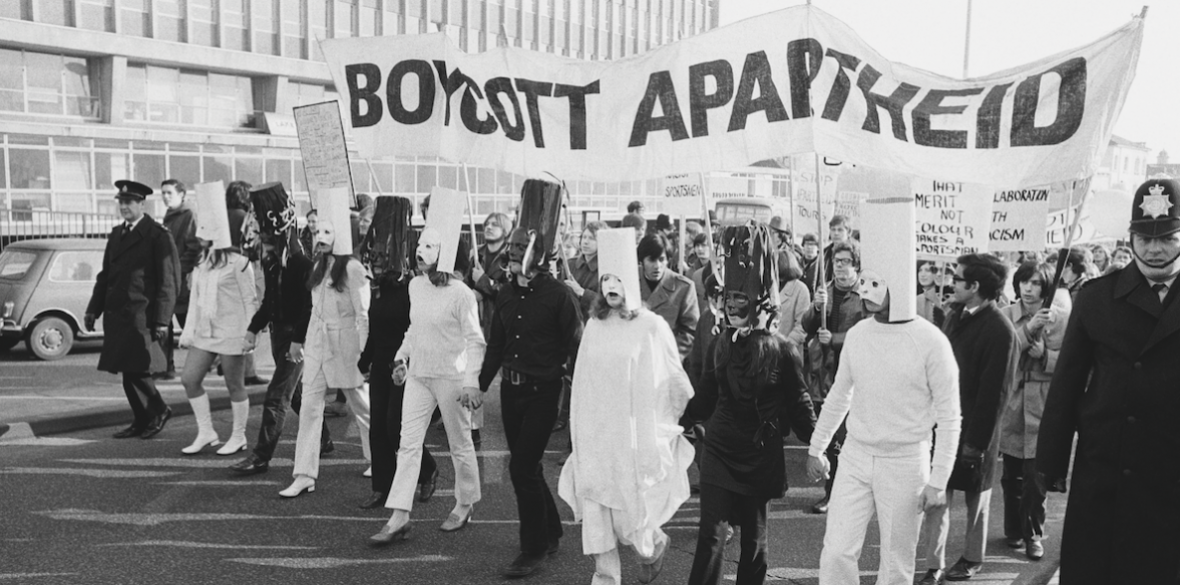

This echoes what Afua Hirsch, writing in the Guardian in 2018, argued about the end of Apartheid in South Africa: “Columnists did not cut it. Activists could not have done it. Peaceful protest did not do it. Sports boycotts, books, badges and car boot sales did not do it. It took revolutionaries, pure and simple. People willing to break the law, to kill and be killed.”

Fellow Guardian journalist Owen Jones agreed, tweeting: “Apartheid was brought down by revolutionaries, not peaceful protest. Brilliant piece by @afuahirsch.”

With all these assertions in mind, it is worth addressing some of the common myths about civil resistance.

Myth: non-violent struggle is not as effective as violent struggle

In their 2011 Columbia University Press book Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Non-violent Conflict, Chenoweth and Maria J Stephan compare the efficacy of non-violent and violent campaigns. Analysing 323 examples of resistance campaigns and rebellion from 1900 to 2006, the authors concluded that non-violent campaigns have been twice as successful as violent campaigns in achieving their objectives.

Research conducted by Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, currently a professor in the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland, broadly supports Chenoweth and Stephan’s thesis. Studying a different data set of violent and non-violent strategies of organisations seeking self-determination between 1960 and 2005, in 2016 Cunningham concluded that non-violent resistance “is more effective than violence in obtaining concessions over self-determination.”

More recently, citing an updated dataset of 627 revolutionary campaigns from 1900-2019, in 2021 Chenoweth re-confirmed her earlier conclusion: over 50 per cent of non-violent revolutions succeeded, compared to 26 per cent of violent ones.

And what about confronting murderous dictatorships? According to Chenoweth and Stephan, “The notion that non-violent action can be successful only if the adversary does not use violent repression is neither theoretically nor historically substantiated.” The removal of General Pinochet in Chile, the downfall of President Marcos in the Philippines, the ousting of the Shah of Iran in 1979 and, yes, the end of Apartheid in South Africa, all show that non-violent struggle has played a decisive role in toppling the extremely ruthless regimes.

Myth: non-violent struggle is passive

In Civil Resistance, Chenoweth explains that “civil resistance is a method of conflict — an active, confrontational technique that people or movements use to assert political, social, economic or moral claims… in a very real sense, civil resistance constructively promotes conflict.”

The strategically brilliant US civil rights movement provides a valuable case study. Writing about the representation of Martin Luther King in the 2014 movie Selma, US journalist Jessica Leber argues the non-violent campaign he led for African-US voting rights in 1965 “was incredibly aggressive, brave, and strategic — in many cases aiming to force the state into violent opposition.”

The same applies to the successful campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference he led put together and executed a detailed plan for mass confrontation with the city’s white power structure. Writing in his famous Letter From a Birmingham Jail, King noted: “The purpose of our direct action programme is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.”

If anyone wants to read more about this extraordinary strategic intelligence, I would strongly recommend the 2022 book Waging A Good War: A Military History Of The Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968 by Thomas E Ricks.

Myth: The success of non-violent struggle is based on appealing to the better nature of the enemy

“Civil resistance works not by melting the adversary’s heart,” Chenoweth explains in her Civil Resistance book. Chenoweth and Stephan elaborate in How Civil Resistance Works: “non-violent campaigns achieve success through sustained pressure derived from mass mobilisation that withdraws the regime’s economic, political, social, and even military support”.

The Indian independence movement led by Gandhi, the US civil rights movement, the struggle for independence in Ghana and Zambia, and Otpor’s ousting of Slobodan Milosevic in Yugoslavia — the oppressors in these examples of successful civil resistance didn’t suddenly discover their better nature. They were forced to make concessions because of the unstoppable power of the movements they faced.

Myth: In the face of repression, non-violence will mean lots of defenceless people get killed

After analysing a dataset of 308 resistance campaigns between 1950 and 2013, Evan Perkoski, an Assistant Professor at the University of Connecticut, and Chenoweth highlight a “counterintuitive paradox” — that those campaigns which remain non-violent and unarmed with no significant foreign support are safest from mass killings. “Non-violent uprisings are almost three times less likely than violent rebellions to encounter mass killings, all else being equal,” they conclude in a 2018 International Centre on Non-violent Conflict research paper.

Similarly, Chenoweth, citing her expanded and updated dataset, confirmed in 2021 that “non-violent campaigns aimed at dislodging a power structure between 1946 and 2013 suffered remarkably fewer fatalities than their armed counterparts” — 105 deaths per year compared to 2,800 deaths per year.

For example, the largely non-violent 2011 uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt overthrew Tunisian president Ben Ali and Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak with a relatively low number of deaths (estimated to be around 340 and 850, respectively). In comparison, the violent 2011 uprisings in Syria and Libya led to hundreds of thousands of deaths, as well as millions of refugees, a huge increase in international terrorism and the decimation of those countries’ economies.

When I interviewed him in 2011, non-violent action guru Gene Sharp highlighted how the Baltic states won independence from the Soviet Union in 1990-91 — primarily using civil resistance. “They got out with very few casualties. I think in Lithuania it may have been 14 dead, in Latvia eight and in Estonia nobody was killed,” he noted.

Myth: non-violent struggle takes a long time

According to Chenoweth and Stephan’s 2011 study, on average non-violent struggles either succeed or fail three times faster than their violent counterparts — likely one reason why non-violent struggles generally experience less mass killings.

Again, it is instructive to compare the largely non-violent revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia with the violent uprisings in Libya and Syria. The movement sparked by the self-immolation of fruit and vegetable seller Mohamed Bouazizi took four weeks to overthrow Ben Ali, while Mubarak was toppled after just over two weeks of demonstrations. In contrast, Libyan leader Gadaffi was overthrown (with US-British-Nato assistance) after eight months, and the Syrian civil war has now gone on for well over a decade.

★ ★ ★ ★ ★

TO be clear, I do not think those of us living in relative privilege in Britain should judge anyone living under occupation who takes up arms against their oppressor (though, of course, I do condemn attacks on civilians).

It’s possible civil resistance may not work in some settings. And obviously, the academic evidence I cite in support of my argument is not above criticism or revision.

However, I do think it’s important to consider and publicise the evidence for the efficacy of non-violent and violent resistance on a general level. Because it seems to me the left’s ignorance of non-violent struggle has potentially damaging ramifications for the fight for a better world — namely the dismissal of what Professor Stephen Zunes has called “the most powerful political tool available to challenge oppression.”

Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs To Know by Erica Chenoweth is published by Oxford University Press.

Follow Ian on X @IanJSinclair.