This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THESE days, Valentine’s Day is a huge boost to the floristry, greetings card and chocolate industries.

Most of it is a rip-off but it did get me thinking — perhaps it was all the cards, bouquets and boxes of chocolates that have arrived at home recently. Thanks, readers.

The Victorians sent gifts of blooms, plants and specific floral arrangements that were used to send a coded message to the recipient, allowing the sender to express feelings which could not be spoken aloud in prim Victorian society.

They even invented a pseudo-scientific name for the language of flowers. They called it floriography. It turns up in some unlikely places today.

Meaning has actually been attributed to flowers for thousands of years, and some form of giving meanings to flowers has been practised by traditional cultures across the globe.

Plants and flowers were given coded meanings in the Song of Songs, part of the Hebrew Bible.

Today in Britain, one of the most significant examples of attributing meanings to flowers happens around Remembrance Day on November 11.

Huge numbers of people wear the red poppy. Sales of poppies raise money for disabled ex-servicemen and women’s charities — money that you would have thought would come from a grateful government.

Why the poppy? Poppy seeds can remain inert for centuries. Some poppy seeds buried with Egyptian pharaohs have been successfully germinated centuries after they were buried.

Normally poppy seeds remain in the ground until ploughing or some other major earth disturbance brings them to the surface where air and light cause them to germinate.

In the battlefields of the first world war in France and Belgium that massive disturbance came from heavy shelling, tanks and the infantry themselves.

After each battle came a huge flush of blood red poppies. After the poppies came the poppy poems. Some claimed it all a miracle.

After the war injured soldiers were soon put to making and selling paper poppies.

Some people thought those blood red poppies looked as if they glorified war and in 1926, a few years after the introduction of the red poppy in Britain, the idea of pacifists making their own white poppies was put forward by members of the No More War Movement.

Their intention was to remember casualties of all conflict, and to hope for the end of all wars.

In 1933 the first white poppies were sold by the Co-operative Women’s Guild.

The Peace Pledge Union joined in their distribution from 1936, and white poppy wreaths were laid from 1937 as a pledge to peace that war must not happen again.

Today thousands wear the white poppy either on its own or alongside a red poppy.

In Northern Ireland the two poppies have provoked a far louder argument.

Those who wear the white poppy or simply boycott the red poppy argue that the red bloom also conveys a specific political standpoint, and point to the divisive nature of the red poppy which is worn mainly by unionists but boycotted by Irish republicans. Here the language of flowers has an Irish accent.

For suffragettes, demanding the vote for women, flowers and what they represented were important.

The suffragette colours, green and purple, were represented by purple violet flowers and the plant’s green leaves.

An embroidery by Janie Terrero (now in the Museum of London) commemorates “Mrs Pankhurst’s Bold Mad Ones” arrested for window-smashing in March 1912.

Headed “Deeds Not Words,” the embroidery lists those force-fed in Holloway prison. Their names are stitched around a wreath of violets tied with a purple bow.

Real violet posies were advertised in suffragette journals by the Misses Allen-Brown from their specialist violet nursery at Henfield Common in Sussex.

Violets were cultivated here for nearly 50 years until it finally closed in 1953.

Many years later violets and the colour violet became a undercover code used by lesbians and bisexual women.

The symbolism of the flower derives from several fragments of poems by Sappho in which she describes a lover wearing garlands or a crown with violets.

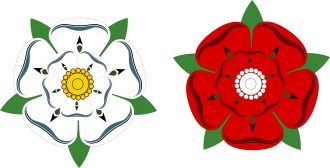

William Shakespeare ascribed emblematic meanings to flowers, especially in Hamlet. In his Henry VI, English noblemen pick either red or white roses to symbolise their allegiance to the Houses of Lancaster or York.

Inhabitants of those two rival northern counties still show their allegiance wearing the appropriate colour rose.

Some historians claim the language of flowers had its roots in Ottoman Turkey, specifically in Constantinople. They are of course famous for breeding so many spectacular tulips here in the 18th century.

Many of their exotic highly bred and crossbred tulips still feature in our bulb gardens today.

The early language of flowers had two great proponents. One was Englishwoman Mary Wortley Montagu who brought it to England in 1717.

The other was Aubry de La Mottraye who introduced it to the Swedish court in 1727.

Books were soon published and many used the new techniques of colour printing.

Robert Tyas was one popular British flower writer, publisher and

clergyman, who lived from 1811 to 1879.

His book, The Sentiment of Flowers, or Language of Flora, was first published in 1836.

One of the most familiar books is The Language of Flowers in an edition illustrated by Kate Greenaway.

First published in 1884, it continues to be reprinted right up to today.

Saint Valentine (c226-270 CE) was a Roman martyr who had tried to cheer up Christians about to be eaten by lions in the Coliseum.

He also had a sideline in secretly marrying Christian couples, defying the ban on such weddings by Emperor Claudius. For this he was beheaded beside one of the gates of Rome.

The feast of St Valentine on February 14 was first established in 496 by Pope Gelasius I.

By the way, Valentine is not just the patron saint of lovers but also of those with epilepsy.

If you are really keen on St Valentine take yourself off to Saint Valentine’s very modern church in Rome. It was built in 1960 to serve the Olympic Village.

A more creepy sight is the saint’s actual skull, always crowned with flowers, exhibited in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, also in Rome. It attracts huge crowds on Valentine’s Day.

Nearer home the Carmelite Church in Whitefriars Street Dublin has many relics of the saint. It also continues to be a popular place of pilgrimage, especially on Saint Valentine’s Day for those really seeking love or just really old bones.

We on the left have our own language of flowers. The Levellers were a group of radicals who during the years of the English civil war challenged the control of parliament.

Between July and November 1647, they put forward plans that would have bought true democracy to England and Wales and have threatened the supremacy of Parliament.

The Levellers used to wear a sprig of rosemary in their hats to secretly identify them to comrade Levellers.

In Islington an ancient pub where the Levellers met is still a pub called the Rosemary Branch. Today it is also home to a popular and often radical arts theatre.

Over the years I’ve been lucky enough to spend a few May Days in Paris.

The street rallies, marches and evening celebrations all have a wonderful perfume about them from the huge quantities of lily-of-the-valley that French communists hand out or sell to raise funds.

Sales of flowers on public streets are normally forbidden but they are permitted on May Day.

May 1 became a public holiday in France in 1947. Now each May Day, thousands of roadside stalls selling lily-of-the-valley spring up.

There is a tradition from 1560 when knight Louis Girard presented King Charles IX with a bunch of the pretty wild woodland flower.

Post-war the flower had become a symbol of the French resistance against the Nazi occupiers and the French communists who played a massive part in that resistance.

Such a delicate, sweet-smelling flower to celebrate communists battling against the stench and obscenity of the Nazis.

The Easter lily is a wild canna lily flower and is worn at Easter by Irish republicans and me — I grow them in my garden — as symbol of remembrance and support for Irish republican heroes who died in, or were executed after, the 1916 Easter Rising.

The Labour Party has its red rose but sadly it isn’t as consistent in its use of this remarkable floral political statement as it deserves to be.

It was women textile workers on strike in the US who first demanded they be given “Bread and roses.” They are still things we should be demanding today.