This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

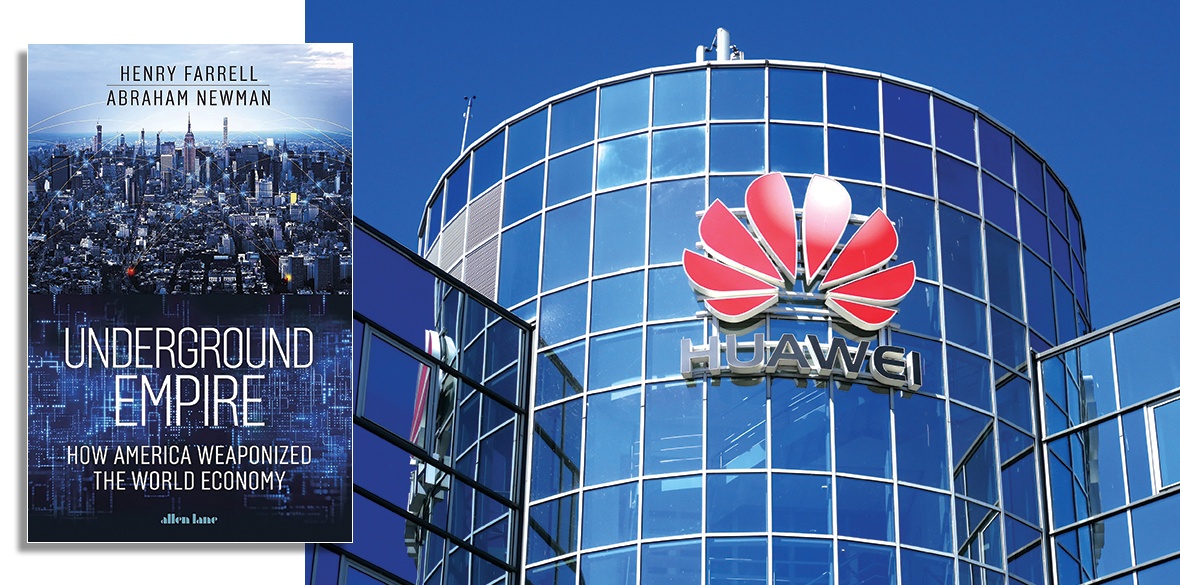

Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy

Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman, Allen Lane, £25

EMPIRES historically relied upon roads to maintain military and economic control over distant provinces, as these routes facilitated the movement of armies, trade and ideas. US political scientists Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman reveal that this concept remains valid in the modern era, except that nowadays these routes include fibre-optic cables and cyberspace.

These unseen highways were often created or commandeered by the United States (albeit sometimes more by accident than design) and later used with increasing ruthlessness to maintain control over the global flow of information, money, intelligence, technology and trade.

Farrell and Newman explain how the status quo is the antithesis to the dream of globalisation’s early pioneers who imagined a world where the flow of ideas and free trade would transcend the power of nation states such that even autocratic governments would find their barriers swept away. Rather, the very opposite occurred with increased centralisation and control becoming the norm as the US and its allies used new technologies that are interconnectedly inherent to globalisation as tools to expand their influence and surveillance across the globe.

Farrell and Newman provide a timeline of how the international banking system became globalised with the emergence of the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (Swift). They explain how the US subsequently took control of this Belgium-based organisation and weaponised it against nations deemed unfriendly to inflict economic pain, while coercing non-US banks and other nations to acquiesce.

The authors also discuss how cryptocurrencies emerged as an attempt to supplant the US dollar and other currencies, circumvent sanctions and create a financial system beyond the reach of government before the latter launched an inevitable backlash.

The book describes at length how the US has used so-called levels and chokepoints within its underground empire to enforce economic sanctions against Iran and deprive its main competitor China of technology that could enable it to produce cutting-edge semiconductors of its own.

The US’s rivals have subsequently sought to forge their own underground empires or find routes beyond the US’s watchful eye, leading to increasing confrontation between global powers.

There is a detailed description of how the US government laboured to constrain the rising influence of Chinese technology corporation Huawei, a front in the ongoing battle for economic and technological supremacy between the US and China into which even large private corporations have found themselves unwillingly conscripted.

While acknowledging that US conduct has alarmed both friend and foe and ultimately makes the world a more dangerous place, as it causes other nations to act in a defensive manner, the authors nevertheless believe that the US could use its power for benevolent purposes to create global consensus instead of confrontation.

The book is overall an engaging read and contains many intriguing insights illustrating the workings of international trade, the global financial system, electronic surveillance by intelligence services, and how sanctions work. However, in parts, the level of detail provided, or the terminology used, reads like a scholarly paper or technical manual. Such sections may however appeal to academics with an interest in the field.