This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

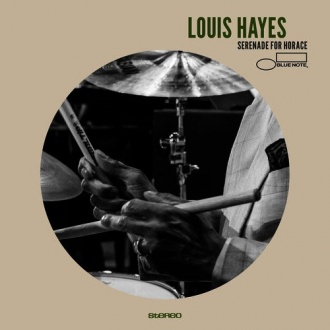

Louis Hayes

Serenade for Horace

(Blue Note)

WHEN the “Hardbop Granpa” Horace Silver died in 2014, the drummer who was an essential part of his most famous recorded sessions for the Blue Note label between 1956 and 1959, Louis Hayes, had a deep compulsion to create a memorial album in the true spirit of his old piano maestro.

Silver, of Cape Verdean heritage, was born in Norwalk, Connecticut, in 1928.

With drummer Art Blakey he formed the original Jazz Messengers in 1954, blending bop, gospel, rhythm and blues and Latin rhythms into a powerfully groovy amalgam.

By 1956 he was leading a very young but potentially stellar band for the epochal album Six Pieces of Silver, with the 19-year-old Detroiter Hayes on drums.

Silver was 28, bassist Doug Watkins was 22, trumpeter Donald Byrd was 24 and tenorist Hank Mobley was 27.

The Blue Note albums kept coming, mainly with Silver compositions, and by Finger Poppin’ of 1958, he had established his most creative horn section with two virtuosi from Florida, saxophonist Junior Cook and trumpeter Blue Mitchell.

So it was quite a challenge for the octogenarian Hayes to create a now-times tribute to such legendary sessions.

He found a very able and experienced tenorist in the 45-year-old New Yorker Abraham Burton, and a vibrant vibes innovator in the 62-year-old veteran of Pittsburgh, Steve Nelson, but it was bassist Dezron Douglas — whom I last heard at Ronnie Scott’s playing with Ravi Coltrane — who brought in two brilliant young lions, trumpeter Josh Evans and pianist David Bryant, making the band a fusion of at least three generations.

The tribute begins with Ecaroh (read it backwards) from the 1952 trio album with Blakey and bassist Curley Russell.

The Latin beat with Hayes’s cymbal strikes gives a true resonance to Nelson’s solo with Burton’s darkly ringing notes and Bryant’s chorus of Silverian life.

It leads on to the famous track from Five Pieces of Silver, the marching Senor Blues.

Both Burton and Evans have evocative solos and Nelson’s mallets chime out the time and place. Bryant’s chorus brings the band back home.

Gregory Porter adds a sensitively sung vocal to the title track of the 1963 album Song for My Father.

Hayes’s rimshots and empathetic solos from Burton Nelson and Bryant add to the filial atmosphere.

Then on to Hastings Street, written by Hayes as a dedication to a street of music in his boyhood Detroit which “had some powerful stuff happening.” Bryant’s solo gives more than an inkling of it and Evans tears in to show its excitation. Hayes’s storm of drums relives his memories.

Strollin’ is from the 1960 album Horace-Scope and Evans and Douglas do much more than go for a stroll to Silver’s memorable tune, with Hayes’s toms well to the fore.

It is Douglas too who leads away on Juicy Lucy from the Finger Poppin’ album. Burton’s solo is a portrait of her, and Nelson’s springing chorus tells us more.

Silver’s Serenade is the title tune of a 1963 album, and all members shine with Burton’s sheer power and Nelson’s complexity prefacing an assured solo by Bryant, sharing the keyboard blood of his eminent forebear.

He continues in the same vein in a piano trio version of Lovely Woman from the Song of My Father album.

Slow and bluesily beautiful with a poignant intervention by the earthy Douglas, you only wish that Silver could have heard and marvelled at it.

Next up is the waltz-time Summer in Central Park from the later 1972 album In Pursuit of the 27th Man. Hayes’s clicking sticks support Burton’s deep lyricism and the urban poetry of Nelson’s vibes.

St Vitus Dance is one of the tracks of Blowin’ the Blues Away of 2959. Its lightweight, fleet-footed melody is an apt vehicle for this band.

Burton sounds carefree, Bruant swings jauntily and Nelson is levitating as his notes sprinkle across the studio floor.

This record, beyond its own achievement, is an invitation to revisit all those momentous Silver Blue Note albums.

Hayes is imploring you to, right up to the final notes of Room 608 from Silver’s first dramatic 1954 Jazz Messengers album which closes Serenade for Horace, expressing Silver’s musical genius in the heart of the present.

Chris Searle on Jazz appears every Tuesday in the paper edition of the Morning Star.