This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

The Anschluss, the “joining” of Austria with Germany, took place with the invasion of German troops on March 12 1938 and its formal announcement the following day in Vienna.

It was less of a “joining” than an annexation of Austria by Germany, following the resignation of Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg, assisted by Austrian nazis who sold out Austria from within.

It meant, as well as an horrific offensive against the Jewish community of Austria, a calculated advance towards much larger international aggression.

US journalist William Shirer, much later author of the widely read The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, confided to his diary in Vienna on March 12: “The worst has happened! Schuschnigg is out. The nazis are in … Hitler has broken a dozen solemn promises, pledges, treaties. And Austria is finished! … Gone. Done to death in the brief moment of an afternoon.”

That day the British Communist Party issued a statement which included: “Unless fascist aggression is stopped now, fascist aeroplanes will be over Prague.”

The most graphic first-hand account of the Vienna events may be that of Eric Gedye in his passionately written Fallen Bastions, published by the Left Book Club in 1939. Daily Telegraph correspondent Gedye was in the Vienna press office when the Anschluss announcement was made, but Hitler had not yet shown his face in Austria’s capital.

As Gedye explained, the nazi leader’s arrival had been held up by mechanical problems experienced by tanks and other vehicles. When he arrived on March 14, he spoke only briefly from a balcony. The next day he told a huge admiring crowd that Austria would provide a buffer against the threat from the east. In reality, the threat was to the east and from the nazis.

Descending from the press office to a courtyard, Gedye hoped to get to see Hitler, together with Austrian staff officers who were for the first time wearing swastika armlets. Instead, a nazi commander told them to back up into the building or be fired on.

A Reuters colleague managed to telephone a headline sentence from the press office. “I am here with the entire foreign press imprisoned in the Chancellery under threat of being fired on by German troops if anyone attempts to leave.”

But nazi confidence was not unbounded. The nazi ambassador in Prague sought assurances from the Czechs they would not react to the Anschluss by mobilising their own forces and a promise was given that nazi troops would not approach the Czech frontier. Gedye was soon expelled from Austria, while ex-chancellor Schuschnigg was in nazi custody until 1945.

Immediate consequences of the nazification of Austria included the wholesale dismissal of Jews from their employment and the confiscation of Jewish-owned shops.

Much private plundering took place, as well as plundering for the Reich, and the Austrian national bank’s gold reserves were soon on their way to the Reichsbank in Berlin.

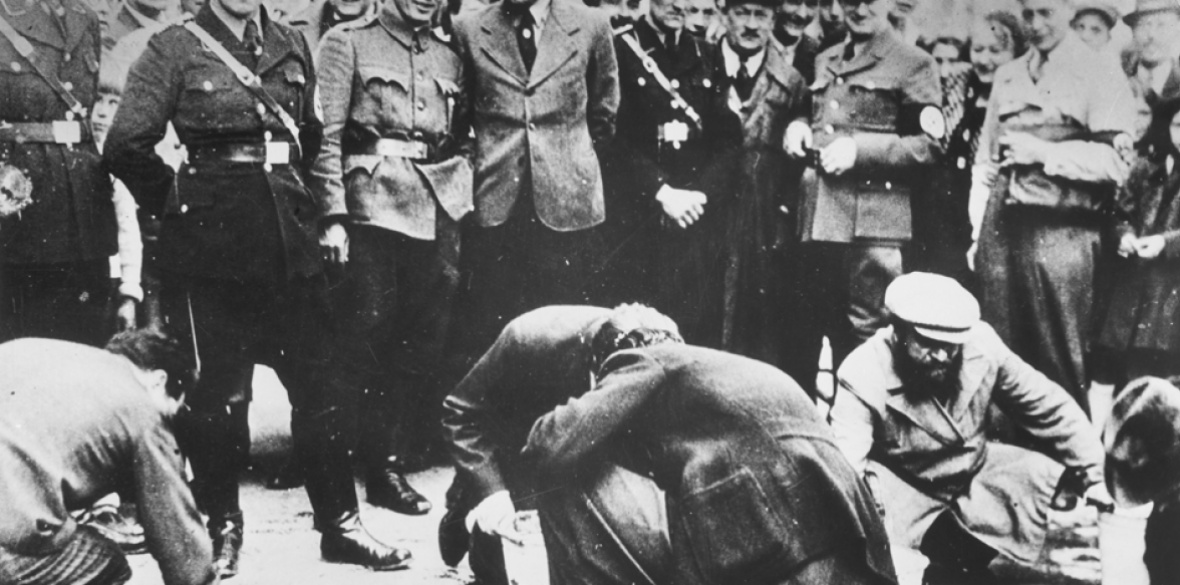

Abhorrent behaviour towards the Jews of Vienna was observed with disgust by Gedye, recording: “With the full approval and support of the police … the Austrian Jews were everywhere to be seen under brown-shirted guards scrubbing pavements and cleaning lavatory bowls with their bare hands to make a German holiday.” Many suicides by Jews followed.

In summer 1936, communist Palme Dutt — editor of the Daily Worker 1936-8 — had, in his own Left Book Club classic World Politics, considered the international position as it was then, just before the outbreak of the Spanish war.

First looking back at the Versailles treaty and the advent of Hitler in power in 1933, he summarised: “What had been sternly denied to parliamentary democratic Germany, which was weak, defenceless and sincerely wanting peace, was now poured out with eager hands to nazi Germany, which was armed, aggressive and openly preparing war.”

He itemised six stages in which other countries, including Britain, had facilitated the nazi offensive “to ever closer readiness for war.”

Agreement for Germany to rearm significantly was followed by the German-Polish treaty of January 1934 (directed against the Soviet Union), the nazi rising in Austria in July 1934 (directed from Germany), the re-establishment of conscription and overthrowing of Versailles military controls in 1935, the Anglo-German naval agreement of June 1935, and the remilitarisation of the Rhineland in March 1936.

“Where will the next blow fall?” asked Dutt. “The expectation has been widely expressed that the next blow may fall in Austria or Czechoslovakia.”

It proved to be Spain, where the generals’ revolt of July 1936 was followed by substantial nazi and Italian fascist armed support as well as by the arrival in Spain of communists and socialists ready to give their lives against fascism and for the democratic republic.

Days before the Anschluss, on March 8, Soviet ambassador to Britain Ivan Maisky weighed up Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain coolly in his diary.

“Here, he is often called the ‘accountant of politics.’ He views the whole world primarily through the prism of dividends and exchange quotations,” Maisky wrote.

“At the same time, Chamberlain is very obstinate and insistent and, once an idea has lodged in his head, he will defend it until he is blue in the face.

“A particularly important trait of Chamberlain’s character is his highly developed ‘class consciousness’ … He believes in capitalism devoutly … This makes him a vivid and self-confident representative of bourgeois class-consciousness.

“Indeed, Chamberlain is a consummate reactionary, with a sharply defined anti-Soviet position.”

Chamberlain’s response to the Anschluss was encapsulated in a private letter of March 13, which illustrated his fixed idea that he could do deals with Hitler and yet keep Britain safe.

“Heaven knows, I don’t want to get back to alliances, but, if Germany continues to behave as she has done lately, she may drive us to it.

“If we can avoid another coup in Czechoslovakia, which ought to be feasible, it may be possible for Europe to settle down again.”

Dutt had suggested in World Politics how the nazi offensive could be checked. “If the existing Franco-Soviet pact were reinforced by a corresponding Anglo-Soviet pact (equally open to other signatories), if British policy could be transformed by mass pressure from its existing diplomatic support of nazi Germany and refusal of all commitments for peace outside Western Europe, to unity with the Soviet Union, France, the Little Entente, the Balkan Entente (ie Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Romania) and the smaller countries for the collective maintenance of peace against aggression, then a strong barrier could be built in the immediate present situation.”

All this was as true in March 1938, as it had been two years earlier, but Chamberlain, backed by most Conservative MPs, was desperate to avoid any alliance with the Soviet Union against Hitler and was pleased by the prospect of a Francisco Franco victory in the Spanish war.

On March 9, Franco’s army, supported by nearly a thousand German and Italian aircraft, and many Italian soldiers, opened a major offensive on the Aragon front. It drove for the Mediterranean to cut the republican area in two, while Barcelona was bombed mercilessly.

Nevertheless, despite severe losses, the British Battalion and other foreign volunteer units were fighting on. John Peet, former guardsman and volunteer — also future editor of the weekly German Democratic Report — wrote home on March 31 that “thousands of people who have been working in the rearguard after being wounded or sick are volunteering to go back to the front again.”

Historian Richard Overy commented, in his The Road to War, that the Anschluss, unimpeded by international reaction, “opened the way to the German domination of eastern Europe. The almost complete lack of resistance to union with Austria made a settlement of the Czech question an opportunity that could not be resisted.”

In the Commons on March 14, intransigent imperialist and dissident Tory Winston Churchill was out of tune with Chamberlain, commenting: “What is there ridiculous about collective security? The only thing that is ridiculous about it is that we have not got it.”

Today’s international situation, in which Britain’s government continues to appease and participate in US imperialism conducted via market domination, unholy collaborations and subsidies, cynical human rights excuses and war, war, war — with accidental or intended nuclear conflict easily imaginable — is as troubling as that in March 1938.