This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“MY COMRADES in the Warsaw Ghetto perished with their weapons in their hands ... It was not my destiny to die as they did, together with them.

“But I belong to them and in their mass graves … perhaps by my death I shall help to break down the indifference of those who have the possibility now, at the last moment, to save those Polish Jews still alive from certain annihilation…

“I wish that the surviving remnants of the several millions of Polish Jews could live to see, with the Polish population, the liberation that it could know in Poland, in a world of freedom and in the justice of socialism.”

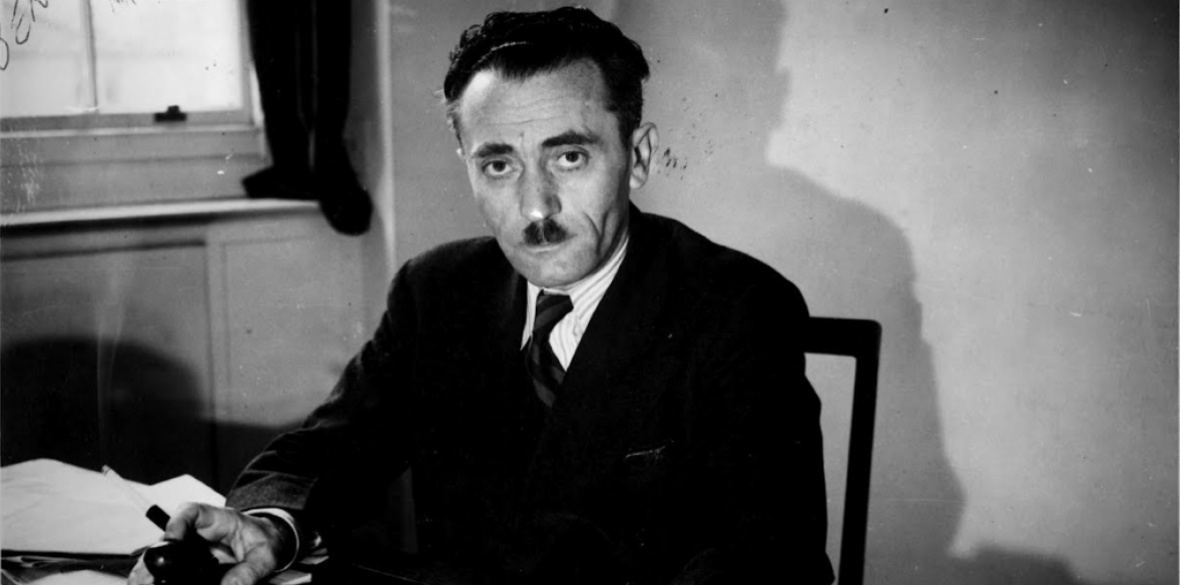

The above quotes are an extract from a handful of suicide letters, left on a table in his London flat 75 years ago, by Szmul Zygielbojm, a Polish Jewish socialist, when he knew that the Ghetto Revolt had been extinguished.

His letters, addressed to allied leaders, the exiled Polish government and close political associates, made clear that his action was a political protest. He addressed one more letter to his landlady apologising for the distress he would cause her.

Zygielbojm, a factory worker at the age of 10, a glovemaker from 12, had been a councillor in Warsaw and Lodz, secretary of the Metal Workers Union, and represented Jewish trade unions in the Federation of all Polish Trade Unions.

When the nazi occupiers had instructed Jewish community leaders to build the ghetto walls, Zygielbojm told a large gathering of Jews not to go voluntarily into the ghetto.

The Gestapo demanded he attend “an interview.” His comrades hid him, obtained false identity papers and sent him to western Europe with a mission to reveal to world leaders the fate of Jews under nazi occupation and demand extraordinary action to rescue them.

From March 1942, until he took his own life, aged 48, in May 1943, Zygielbojm lived alone in London, representing the Jewish Socialist Bund in the exiled Polish National Council.

For 14 months, he bombarded political leaders, diplomats, the press and trade unions with first-hand information from the ghettos collected through underground resistance networks.

In a BBC broadcast in June 1942, he spoke of “Jews in the ghettos who … see their relatives dragged away en masse to their death, knowing only too well that their own turn will come.”

At a Labour Party protest meeting at Caxton House in September 1942, he revealed horrific details of the nazis’ first use of poison gas in carrying out mass murder. In just seven weeks, he declared, 40,000 Jews in Chelmno had been herded into vans and gassed as they were driven to mass graves in the forests.

The Warsaw Ghetto revolt began on April 19 1943. The nazis’ plan to liquidate the ghetto and kill or deport its remaining 30,000 inhabitants was blocked for three weeks by an astonishing guerilla campaign waged by 220 Bundists, communists and left-wing zionists aged between 13 and 40 years, using smuggled and improvised weapons.

On May 8 1943, most of the surviving fighters were holed up in a bunker beneath 18 Mila Street at the heart of the ghetto. The nazis threw in tear gas to force the occupants out.

Most of the fighters, including their commander Mordechaj Anielewicz, killed themselves rather than allow the Nazis to murder them.

Around 40 fighters, though, escaped through a rear exit into the sewers, emerging outside the ghetto seeking hiding places or heading to the forests to link with partisans.

The day the revolt began coincided with the Bermuda Conference at which British and US politicians and diplomats met for 11 days but failed to agree any plans to rescue Jews or offer sanctuary to refugees. Zygielbojm received this news as a bitter blow.

On May 11, when he knew for certain that the ghetto revolt had been crushed, he wrote his suicide letters and, that night, he ingested poison in his Paddington flat.

At that moment, Zygielbojm believed that his closest family in Poland had all been exterminated, but one son, Joseph, had fought as a Red Army partisan, survived and settled in the United States.

Seventy-five years on, Szmul Zygielbojm’s extraordinary story still remains relatively obscure, largely for ideological reasons.

It casts an uncomfortable shadow over the manner in which Britain’s military objectives were defined and prioritised. Civil servants dismissed his evidence as exaggerated. His calls for action were ignored by military and political leaders alike as the rescue of Jews undergoing genocide in Poland was not a war priority. Three million of Poland’s 3.3 million Jews were exterminated.

But what of the Jewish community? The movement which Zygielbojm represented, the Bund, was secular, socialist, internationalist and committed to Yiddish culture.

It demanded full equality for all minorities and urged Jews to strive for equal rights wherever they lived. It opposed all nationalism, especially territorial nationalism, and strongly rejected zionism.

In Zygielbojm’s last personal letter in April 1943 to his brother Fayvl, who had escaped from Poland before the war, he excoriated zionists for “exploiting the Jewish tragedy for their political ends,” paraphrasing their spokespersons: “Another 100,000 Jews murdered. Give more money for Palestine.”

Zionism had been a small minority opinion within overwhelmingly working-class Jewish communities everywhere before the second world war, finding more traction among middle-class Jews.

The Holocaust and the appalling aftermath, where survivors languished in displaced persons camps with no country wanting to take them, engendered understandable sympathy for those trying to get refugees to Palestine.

As zionist ideology became more popular among post-war Jewish communities whose class position was shifting, non-zionist and anti-zionist Jews were increasingly marginalised.

Zygielbojm’s story did not fit the post-war consensus established by Jewish communal “leaders” that emphasised the precariousness of diaspora and redemption and security through Israel.

By the 1960s, teachers in Jewish schools and youth leaders alike were elevating the role of zionist ghetto fighters and airbrushing out Bundists and communists. They drew a false line between ghetto resisters in 1943 and Israel’s independence fighters in 1948.

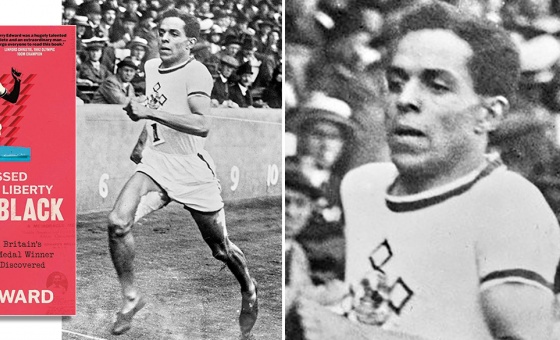

They forgot Zygielbojm and ignored his fellow Bundist Marek Edelman, second-in-command in the uprising, who survived and stayed in Poland, where he affirmed: “We fought for dignity and freedom, not for a territory nor for a national identity.”

Zygielbojm was cremated in London, though his ashes were later interred in a New York cemetery of the Workmen’s Circle, a Bundist-inspired friendly society. A Zygielbojm monument stands there.

Bundist refugees in Canada established a similar monument in a Montreal park. There is a striking tribute to Zygielbojm in Warsaw, along a route “of Jewish martyrdom and suffering” through the former ghetto area.

Here in London, in 1993, a small group of Bundist survivors joined forces with younger members of the Jewish Socialists Group to campaign for a plaque in London.

It was finally unveiled in 1996 by Polish Ambassador Ryszard Stemplowski and Zygielbojm’s daughter-in-law Adele, a survivor of nazi slave labour camps, who came from the United States with her sons for a ceremony attended by nearly 200 people.

At a reception after the unveiling, Zygielbojm’s grandson Arthur said: “People are still being exterminated today because of an accident of birth. Because they are identified with one ethnic group or another.

“His death is not resolved. His message is still unanswered. His cry is not silent.”

Arthur’s brother Paul affirmed that “Szmul Zygielbojm’s labour and sacrifice were not for the Jews alone… amid his anguished pleas for the salvation of a people, he wrote of his belief that a better world would come … a world of freedom, justice and peace.”

We can only speculate what Szmul Zygielbojm would have made of Poland today, where pluralistic and forward-looking Jewish communities are once again growing in 15 cities on Poland.

But they do so in an atmosphere in which all minorities are feeling increasingly threatened by menacing far-right movements who draw confidence and encouragement from a government dominated by the Law and Justice party that indulges in open anti-semitism and Holocaust revisionism, Islamophobia, anti-Roma and anti-refugee racism.

Our own government is directly linked with the Law and Justice party through the Conservative and Reformists group in the European Parliament.

We and our Polish sisters and brothers have work to do!

The Zygielbojm plaque is on the corner of Porchester Road and Porchester Square, Paddington opposite Porchester Hall/Paddington Library, London W2.