This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

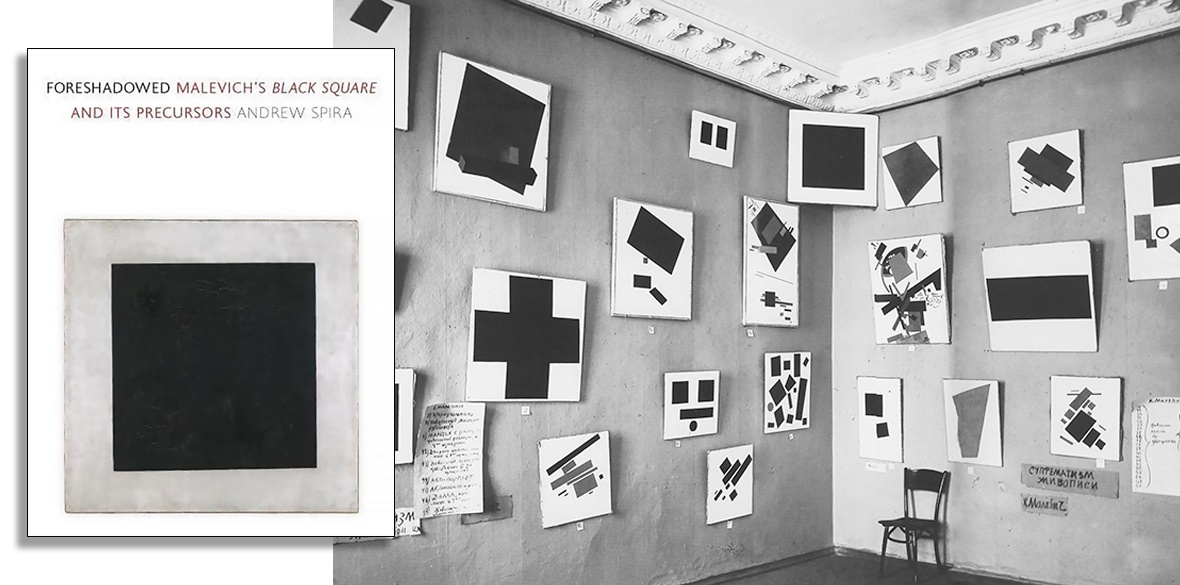

Foreshadowed: Malevich’s Black Square and its precursors

by Andrew Spira

Reaktion Books £16.95

ANDREW SPIRA must be an inspiring art history lecturer. His book on Malevich unfolds as much as a visual argument as a verbal one and is recounted in one breath, as it were, without chapters or headings.

And you feel the canny strategies of a scholar playing to an audience of students.

He opens by asserting that Black Square, 1915, changed art and introduced monochrome painting as a genre that remains “an avant-garde right of passage.” Yet his argument will show the opposite — many images that came before and employ black squares from 17th-century Ethiopian Christian miniatures, to optical experiments, comic novels, cartoons, acts of censorship and the original anarchist flag.

While the visual similarity is apparent such examples are only spurious precursors and anecdotal rather than revealing, and you feel that this display of erudite research into trivia is there to delay the revelation of the one indisputable fact that he has up his sleeve, like a trump card, to explain the genesis of the work.

It’s worth waiting for because it is a convincing case.

Malevich hung the canvas at the Last Futurist Exhibition 0.10 in Petrograd not simply across the corner of a room (like an icon) but where the two walls meet the ceiling, using the painting to address the room “as a cube.” Undoubtedly true … but why?

Spira demonstrates that this was part of a consistent programme to present the “fourth dimension” in art, and rather than being revolutionary, this represents an obscure turn-of-the-century way to think.

The point at issue is how to show time (and therefore eternity) operating within the three dimensions to which we are accustomed and which we do not see beyond.

The Russian esotericist Pyotr Ouspensky, whom Malevich knew through his fellow artist Mikhail Matyushin cast this thought experiment in the terms that Malevich popularised as Suprematism.

If, goes the argument, we were trapped in two dimensions (a flat plane), how would we experience three-dimensional objects passing through it? A circle that got bigger and smaller would be the passage of a sphere. A square would be a solid that appeared, and disappeared, unless it was tilted in which case it would be a triangle, a rhomboid, a trapeze …

These are the shapes of Suprematism — the passage of three-dimensional objects through a two-dimensional surface. And the black square in the top corner of a room is an attempt to use this language to intimate the passage of a fourth dimension through a three-dimensional space. But why?

In the view of the esotericists, the capacity to visualise an object “from all sides at once” is to see it at last in geometrical wholeness and to develop a “higher consciousness.”

This kind of theosophical obscurantism was widespread in the early 20th century and led to similar work in many places simultaneously. Earlier than Malevich and unknown to him is, for example, Hilma af Klint in Sweden who developed her own language of obscure and simple geometries, embraced the mission of “self-negation” and lived as a mystic.

But it was a middle-class phenomenon that couldn’t stand contact with the revolution of 1917.

Malevich stated famously that “Art does not need us and it never did,” but his austere, priestly and optically derived language should be contrasted with that of younger men and women who embraced the revolution (unlike Ouspensky, who fled) such as Lyubov Popova who integrated a Cubo-futurist aesthetic into the industrial production of textiles, and Naum Gabo whose constructivist and kinetic aesthetic were developed in the immediate aftermath of 1917, and continue to influence architecture today.

For them, art might be impersonal but it has practical application beyond mystical enlightenment.

This kind of broader social-political context is beyond the reach of Andrew Spiro, however, whose book prefers to ignore political events and languish in the visual poverty of antiquated pseudo-Christian mysticism.

A shame, as it is a slick little volume.