This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

KEITH ARMSTRONG (1950-2017) was a dynamic activist for the rights of people with disabilities. He was also highly creative, working as an artist, poet and musician, and a serious scholar of the history and linguistics of disability.

He contracted polio during infancy. In his teens he could just about walk but at the age of 20 he spent an entire year in hospital, undergoing complex back surgery. He would spend the rest of his life on crutches and, increasingly, in a wheelchair.

Yet he attended countless demonstrations — for CND, housing rights and against the government of the day, as well as those demanding disability rights — and was arrested more than once.

Keith’s experience of being forced to sit in the guards van on British Rail trains in the 1980s was formative. He strongly felt that he had been treated like a piece of luggage, not as a human.

He adopted the online moniker “ruhuman,” and was involved in the campaign for accessible transport of the ’80s and ’90s, serving on the management committee of Ealing and Camden’s Dial-a-Ride scheme, as well as that of London Transport.

He continued protesting throughout the 1990s and 2000s with the Disabled People’s Direct Action Network (DAN) whose campaigning led to ramps in buses and improvements to tube and train access as well as the introduction of the Disability Discrimination Act in 1995.

It is hard now to recall what the world was like for people with disabilities before activists like Armstrong changed it.

But Armstrong is unique because his activism grew from his early achievement as an artist, as though the experience of himself as an original creator of things was the necessary prerequisite to political action.

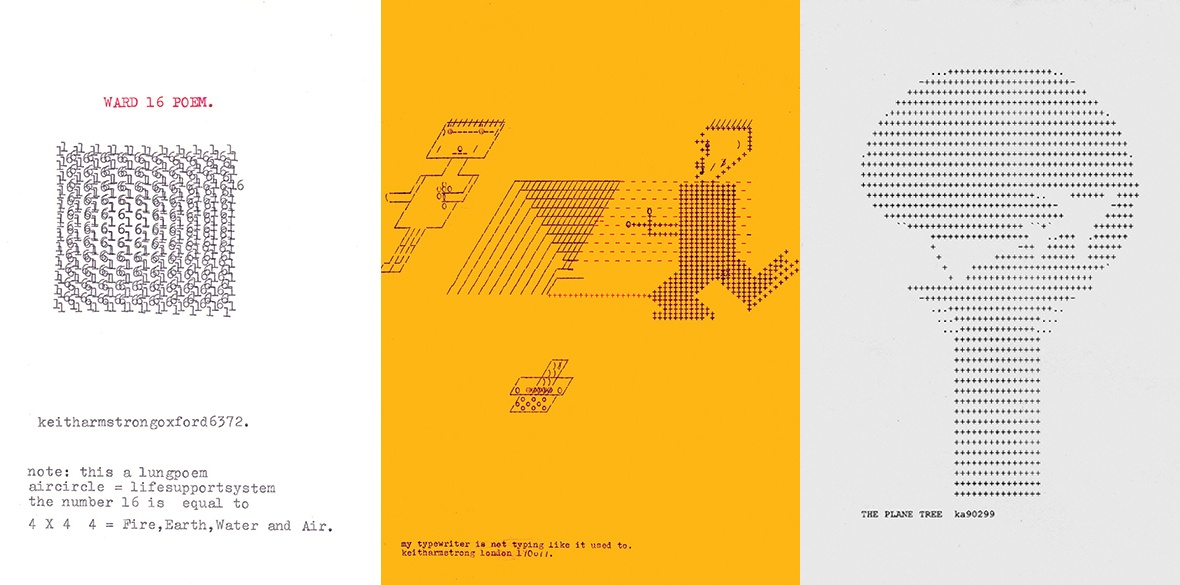

There is a compelling immediacy to that work — the archive of his typewriter prints — that resonates as strongly today as it did at the time, and that deserves comparison with the great names of abstract and Op art, such as Mark Rothko and Bridget Riley.

Due to his disability he often had a self-imposed time limit on how long he could spend at the typewriter and as his mentor Dom Sylvester Houdedard noted: “Here are some of ka’s poems — done with a tautness and cohesion imposed by their 60-minute limit.” That Armstrong could turn these physical limitations to great artistic advantage is part of the inherent beauty of his work.

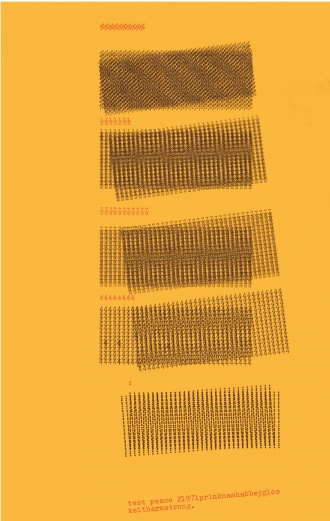

Houdedard was also a practitioner of concrete poetry, and what he shares with Armstrong is the belief that the typewriter could be an instrument, or a conduit for peace. This is knowingly acknowledged by Armstrong in the work Test Peace.

He was extremely prolific during the late ’60s and early ’70s when the Concrete Poetry movement was at its peak in Britain.

In the words of Jasia Reichardt, Concrete poetry: “... serves to examine what happens to language through a certain type of visual presentation, and what becomes of an abstract image simultaneously endowed with a literary meaning.”

Armstrong’s work captures extremes of this.

Armstrong’s was an exceptionally enquiring mind and his poetry explores everything from traditional, formal structures, to texts that use the page as a canvas.

There are pattern pieces, which use a title to suggest a deeper meaning, as well as works that are overtyped to create dense textural statement with no traditional structure alluding to meaning at all.

The visual sophistication of these pieces takes them away from text-based works or poems into pure abstraction. The typewriter’s letterforms become the building up of a series of smaller elements, like the individual stitches used to form a greater whole in embroidery or textile works. Sometimes there are linguistic pointers to give the viewer an imagined or assumed context, but at other times the viewer is left to create their own understanding of the piece — after all, we are a species that seeks to find meanings in patterns.

Armstrong’s more formal written poetry often shows his sense of dissatisfaction with the world, or questions his place in it, but the inherent structure of the pattern pieces enabled by the immediacy of the typewriter is a different, and more positive way of making sense of the universe. When language is broken down into these basic elements, it can be used not to complain or protest, but to celebrate beauty, and being in the world.

Michael Shermer invented the term “patternicity” in 2008 defining it as “the tendency to find meaningful patterns in meaningless noise” and it may be that this search for meaning was eventually better channelled into Armstrong’s activism rather than his poetry, and this explains the relatively brief period period of intense typewriter art activity over his entire career.

He also found musical collaborations very rewarding, pointing out that “John Peel played both sides of my one and only single AN AMAZING GRACE/SPACE BOOGIE on his BBC Radio One show. I also had a cup of tea with him in his London flat...” and he found true equality on the internet, where connections can be made without reference to age, gender or disability.

Having run an international poetry magazine, The Informer, and exhibited widely in the UK, his CV from 1990 barely mentions his poetry writing or art and instead focuses on his activism, community engagement and disability awareness work.

Yet it is these works of concrete poetry that his originality as an artist can be acknowledged, and in later life he returned to them, creating Youtube films that explored and celebrated his early work. These are fascinating films, still in existence on the internet, and highly recommended.

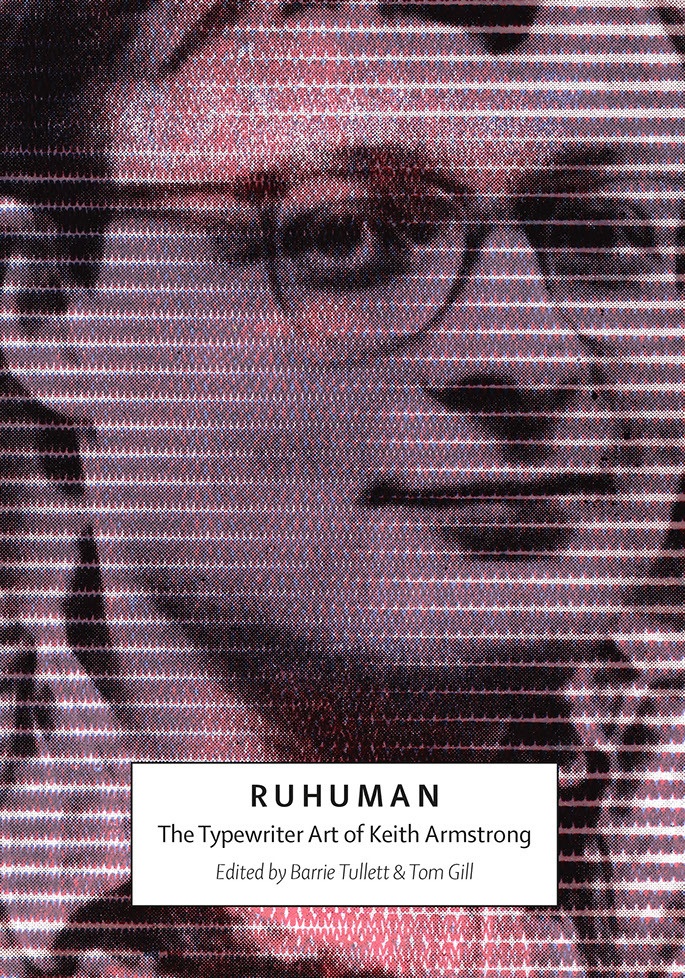

In 2022 a comprehensive and beautiful retrospective of Armstrong’s work was compiled into a book by Barrie Tullett and Tom Gill, with an additional essay by Nicola Simpson. Let’s ensure that this is a step towards Armstrong’s work finding its deserved recognition, a major exhibition, and its place in national collections.

RUHUMAN, the typewriter Art of Keith Armstrong, is published by Caseroom Press and can be bought at the-case.co.uk/ruhuman, £20