This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

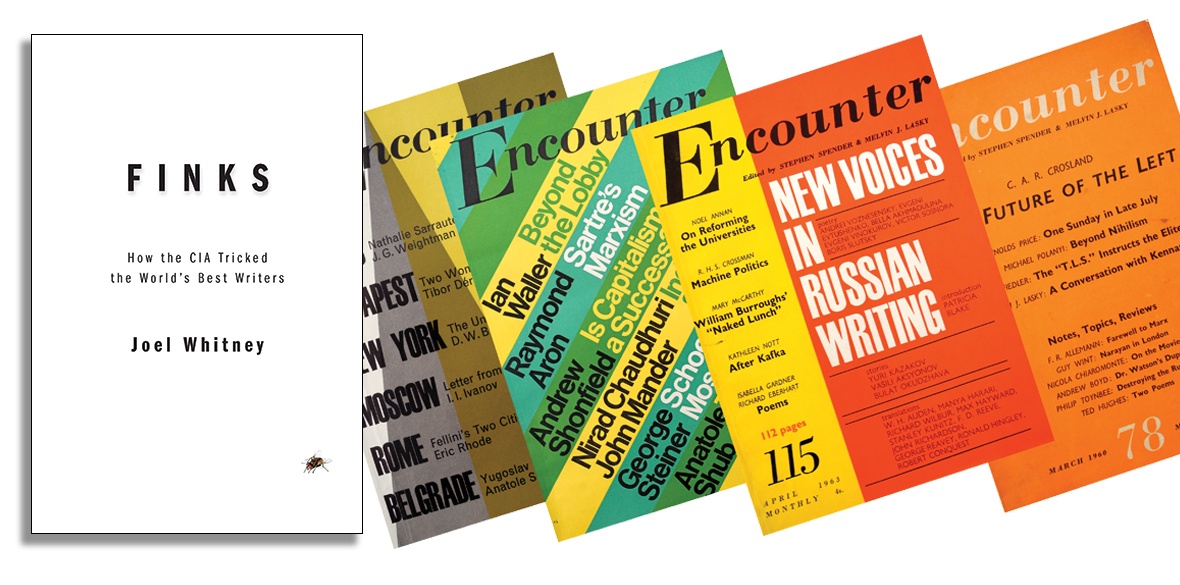

How the CIA Tricked the World’s Best Writers

by Joel Whitney

OR Books £18

JOEL WHITNEY’S book is the latest in a cottage industry of revelations and histories about the cultural cold war fought by the CIA, especially through the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF).

The CCF operated across 35 countries and spawned over 20 magazines which it directly created and oversaw, as well as sponsoring innumerable conferences and the work of artists and film-makers. The operation was covert and magazines appeared broad and non-aligned. Yet the purpose was clear: to marginalise the communist left in the post-war period and boost the image of liberal democracy, the “Free World” and the American way of life.

The CCF’s flagship magazine was the Britain-based Encounter, funded in part by the Information Research Department of the Foreign Office through the British Society for Cultural Freedom. Encounter continued publication until 1991; many others closed after the links between the CIA and the CCF were exposed in 1966. Others continue to this day such as Minerva in Britain, Jiyu (Freedom) in Japan and Quadrant in Australia.

Given the plethora of work on this topic now it is important to consider what Whitney brings to the table.

First, his focus is the Paris Review, ostensibly an organisation with an arms-length relationship with the CCF, but in fact part of a system of syndication in which members or associates of the CCF “Grande Famille” of magazines shared articles. It was founded by three writers, one of whom, Peter Matthiessen, was CIA trained and admitted to using the Paris Review as a cover for his CIA activities. Another, George Plimpton, “consciously aligned” the Paris Review’s mission with the CCF apparatus.

According to one founder the Paris Review welcomed “the good writers, the good poets, the non-drumbeaters and the non-axe-grinders.” Its niche contribution in the CCF family were the interviews it obtained with high profile left-wing writers such as Hemingway and Arthur Miller. Many such writers would later be angered at being used in attempts to parade the vibrancy of Western literature.

Second, in analysing the personnel of the Paris Review he outlines the milieu from which anti-communist leftists developed to become not only complicit in the CIA’s cultural war, but initiated and egged on much of it. Such groupings are now described as the “compliant” or even “imperialist” left.

For Whitney they became part of a process which “starts with well-intentioned men who agreed, winking and invoicing, to promote an anti-communist ideology … and ends with a totalitarian system where secret agents spy on the media and sabotage free speech and press freedom.”

In this regard he emphasises the need to understand the role of the CCF in the context of worldwide military and political aggression.

CCF-affiliated magazines in Latin America “tended to launch just before a US-sponsored coup in the region” and Whitney illustrates the process in Guatemala.

He also tracks the role of a certain John Train, the first managing editor of the Paris Review with alleged ties to the CIA from the 1950s, who in 1980 founded the Afghanistan Relief Committee. It focused on the media and aimed, as explained by Train: “to impose on the Soviet Union in Afghanistan the sort of television coverage that proved fatal to the American presence in Vietnam.”

By setting the cultural war in such a context Whitney offers a more rounded comparison between Soviet censorship and literary control, as clumsily implemented in the Dr Zhivago episode for example, and the secretive methods of the CCF and its affiliates, which proclaimed freedom of expression while vigorously censoring.

With detailed analyses of the shenanigans that accompanied the publication of Dr Zhivago as well as glances at other Encounter-linked magazines in Latin America and India, this book is a fascinating and disturbing read.