This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE masses are not intolerant of gay people. This assertion is the crux of the socialist case against homophobia.

When you can grasp that intolerance doesn’t come from the masses, you can recognise that it is a choice and a form of ideological oppression.

This how the argument was made to recognise and defend gay people in revolutionary Russia.

And yet for Stalin, to whom the argument was addressed, there was no doubt that it was unacceptable. He dismissed the man who made it as an idiot and a degenerate.

That man was a 27-year-old journalist from Edinburgh who was working in Moscow. A working-class intellectual who spoke French, German and Russian, he is the unknown Scottish hero of gay liberation. His name is Harry Whyte, and the year was 1934.

Born in 1907, Whyte had left school at 16 to join the Edinburgh Evening News. Following the General Strike of 1926 he joined the Independent Labour Party, and, moving to London in 1931, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. Immediately he came under state surveillance that would last for his entire life.

He was a jobbing journalist who made it his mission to contribute to the left-wing press.

An intelligence report from 1932 documents his criticism of the Daily Worker, the forerunner of this newspaper.

He objects to the publication of news without a “class twist” and, citing the many accounts of suicide caused by unemployment, he points to the kind of stories that never get published by the capitalist press but that must be the business of the Daily Worker.

His editorial acumen remains as relevant today as it was in the 1930s.

His talents were quickly recognised and by the summer of 1932 he had achieved what must have been a career ambition: to become head of editorial staff at the Moscow Daily News, and a contributor not just to the Daily Worker but to other British and Russian newspapers as well.

He had grasped a key role in history as a principle English-language spokesperson of Soviet Russia.

Although Whyte was one of the most significant left-wing journalists of the period (and of this newspaper) his achievement and his memory have been erased because, in his identity as a revolutionary socialist, he was openly gay.

And, in a way that is rarely seen today, he brought class analysis to bear on the condition of homosexual men.

For Whyte, homophobic laws and homophobic culture go hand in hand with the class system and, as he puts it, “the emancipation of working-class homosexuals is inseparable from the general struggle for the emancipation of all humanity from the oppression of private-ownership exploitation.”

He had grown up in the sexually repressive atmosphere of a Scotland in which homosexuality would remain a crime for his entire life, and from which he had escaped, first to the gay underworld of London, and then via Magnus Hirschfeld’s progressive Institute for Sex Research in Berlin to revolutionary Russia.

By making this journey, Whyte deliberately placed himself inside the first great wave of sexual liberation in the 20th century that was happening in early Soviet Russia.

All laws that regulated and prohibited sexual activity between consenting adults had been abolished in 1917, and the Soviet penal code of 1922 no longer mentioned homosexuality at all.

In 1923, Nikolai Semeshko, Lenin’s commissar of health, described the emancipation of gay men as “part of the sexual revolution.”

In 1925 Grigoriy Batkis, director of the Moscow Institute of Social Hygiene, drew attention to the fact that “homosexuality … which is set down in European legislation as an offence against morality … is treated exactly the same as so-called ‘natural’ intercourse by Soviet legislation…”

The early Soviet revolutionaries were proud to emancipate all the oppressed parts of society and attracted remarkable gay men to their cause from around the world.

Edinburgh’s Harry Whyte is perhaps the most significant of them all because of a remarkably courageous protest that he made directly to Stalin.

His was the only voice to object to the secret recriminalisation of sodomy introduced in 1934.

Normally new legislation was announced and explained in Pravda, but the new law was introduced without public knowledge, as though it were a matter of national defence.

It was a secretive move but had far-reaching consequences: it ushered in decades of regressive abuse of gay men in every country in the Soviet sphere.

The oppression brought about by homophobic legislation and homophobic culture would not be redressed in socialist countries until the 1970s.

It was undoubtedly dangerous to write the letter. Whyte was clearly incriminating himself and risking his membership of the party and his position at the Moscow Daily News.

But Whyte had the intellect to defend gay people from a socialist, class-based point of view.

Today, the cause of gay rights has been appropriated by the right, and for many identity politics eclipse class politics.

Whyte stands in diametric opposition to this, and a communist like Mark Ashton, founder of Lesbians and Gays support the Miners, was his direct heir.

Whyte argued that the persecution of gay men goes hand in hand with the class system, and that the crises of capitalism will give rise to further waves of homophobic repression.

One need look no further than today’s Poland, Hungary and Turkey to see evidence for his approach.

Whyte pointed out the way the bourgeois class avoid a legal punishment that is applied with maximum severity to gay workers, and it is on behalf of that class — the 2 per cent, an estimated two million gay men in Soviet Russia — that he stood up to Stalin.

The letter he sent Stalin was 4,000 words long and argued with passionate sincerity, as though everything depended on it.

The real struggle in his own life was clear from the evidence he presented that homosexuality is innate and he pleaded with Stalin to “recognise as inevitable the existence of this minority in society be it capitalist or socialist…”

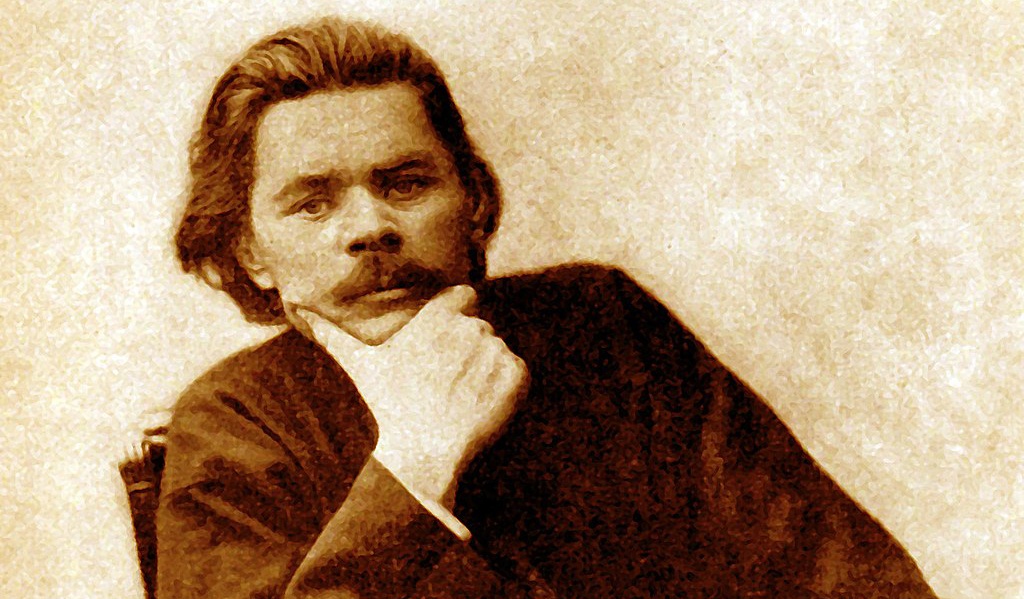

Stalin didn’t reply. But he didn’t arrest Whyte or destroy the letter. Instead, he sent it to the archive and recruited the renowned Russian man of letters, Maxim Gorky, to respond in Pravda.

Gorky’s vitriol speaks for the high political tensions of the totalitarian era. He wrote: “…destroy homosexuals and fascism will vanish…” and Stalin approved.

Hitler had come to power in Germany and the two regimes were locked into a public exchange of homophobic slurs in a propaganda war against the other.

Those insults quickly turned into internal cultures of homosexual oppression and the next three decades were the darkest era of persecution of gay men, whether in Nazi Germany, in the Soviet Union or in liberal, capitalist Britain.

For a gay socialist like Whyte, there was nowhere to turn. But he never gave up a lifelong and persistent loyalty to the Soviet Union.

To protest against Stalin’s homophobic laws didn’t necessitate rejection of the whole socialist project.

Whyte didn’t leave Russia for two years, but by 1936 the party purges expelled him from both the party and the country.

Returning to a Britain he had been glad to leave, he gave his energy to anti-fascism by working for the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, and then working for Reuters in Morocco.

When World War II broke out he applied to be posted as foreign correspondent to Moscow.

His visa was refused by the Russians. Astonishingly, Whyte found another way to return to Soviet Russia, this time as a coder on the Arctic convoys.

His record states that for 18 months he was stationed in Archangel. He had seized the opportunity to use his Russian, to fight fascism and to contribute to the victory of Soviet Russia, but this time as a British serviceman.

After the war he returned to journalism in London, taking up the cause of inadequate demob pay for veterans in Socialist Review, among other articles. In 1950 he moved to Turkey and he died in Istanbul 10 years later.

Whyte’s significance is as a working-class voice defending homosexuality from a Marxist perspective.

His letter to Stalin argues for human rights before human rights existed, and his arguments continue to resonate today.

We can see the vindication of his argument in a case like Cuba. There, a socialist regime that inherited Stalinist homophobic prejudice has grown out of it to become one of the most socially emancipated countries in the world.

The letter was preserved in the secret presidential archives and discovered in 1993.

It was first discussed in Dan Healey’s book Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia (University of Chicago Press, 2001), and subsequently translated and published in English by the Russian artist Yevgeniy Fiks.

An account of Whyte’s life can be found in Dr Jeff Meek’s social history Queer Voices in Post-war Scotland (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Whyte’s life and writing are celebrated in Angus Reid’s exhibition, Parallel Lives, that is currently showing at Summerhall, Edinburgh.