This is the last article you can read this month

You can read 5 more article this month

You can read 5 more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“I CAN’T even begin to describe how overwhelming the situation in Libya and the Mediterranean is,” says Hannah Wallace Bowman, communications manager on board the Ocean Viking, a migrant rescue ship operated by French charities Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and SOS Mediterranee.

“I don't think I will really be coming to terms with it anytime soon,” she says after having spent close to two months at sea and saving the lives of over 650 people.

The Ocean Viking, which launched in August, is MSF and SOS Mediterranee’s return to sea-based migrant rescues. The charities had been operating the Aquarius for several years before, but were forced to stop in December 2018 after what MSF Sea described as “sustained attacks on [its] search and rescue [operations] by European states.”

Once again, instead of allowing the crew to safely carry the rescued to a safe port — as international maritime law requires all sea captains to do — Italy, Malta and the European Union made every effort to prevent the Ocean Viking, and other ships of the civil migrant rescue fleet, from doing so.

Bowman had been on board the Ocean Viking since the beginning. She spoke to me right after disembarking for the first time in over three weeks.

“We’ve seen people who have wounds from melted plastic that has been burnt onto their skin. We had people who were made to call their families to ask for money while they were having physical violence inflicted upon them.

“I can only begin to imagine how devastating that must be to have your brother, your sister, your child on the phone, hearing them going through that pain and not being able to do anything.

“When I actually get a chance to sit and and think about what it is that I have experienced with these people, I’m not entirely sure how easily I’ll be able to reconcile the fact that Europe is allowing this to continue and that we are demonising the people who are doing the work to save these people.”

The EU responded to the so-called “migrant crisis” in 2015 not with rescues but by launching an anti-human-trafficking naval mission called Eunavfor Med, which later became know as Operation Sophia. Though its primary mission was to stem the flow of migrants into Europe, the mission’s ships are estimated to have saved the lives of 45,000 migrants from a watery Mediterranean grave.

However, in April, after pressure from Italy’s then far-right-populist coalition government, the EU agreed to pull Operation Sophia’s SAR ships and increase funds to the so-called Libyan coastguard (LCG), which has been pushing refugees back to the war-torn country ever since.

“As it stands, Operation Sophia has placed all its emphasis on aerial assets,” Bowman says. “So they don’t have any rescue capacity, which means they can watch people from the sky and they can also direct interceptions.

“They can empower the LCG in order to intercept boats. But if they see a shipwreck, they’re pretty powerless to do anything.”

Worse, the Libyan coastguard and Operation Sophia do not collaborate with the civil fleet, even when their ships are in the vicinity of a boat in distress, Bowman says.

“When we've tried to contact the relevant authorities, they simply don’t respond. If they do pick up the phone, they don’t speak English, which is a requirement of of your co-ordination centre.

“So we’re pretty alone out there. At least that’s what it feels like.”

The inhumanity of Europe’s handling the crisis was illustrated on September 20 when the Ocean Viking rescued 35 people in a wooden boat from waters within Malta’s search and rescue area.

The Maltese authorities later sent a vessel to the Ocean Viking to transfer the 35 people picked up in its waters but would not take in the 182 other refugees — including a newborn baby, several children and a pregnant woman — who the crew had saved just a few days before in Libyan waters.

“It was a really difficult moment. We had to explain the reason some people were allowed to get off and others weren’t was simply down this fairly arbitrary division in terms of search and rescue regions.

“We were really worried as to how people were going to respond. But I was incredibly impressed with the level of dignity that people received the news. I certainly wouldn’t have taken it as they did.

“Some of them took off to lay down and cry. Others just took themselves inside and had a quiet moment. It was a really sombre atmosphere on the ship.

“This decision really revealed the level to which this system is so entirely dysfunctional.”

Terrible as this situation was, and how utterly demoralising it must have been for the migrants left on board, it seems it wasn’t as bad as what happened in August on the Open Arms, a NGO migrant rescue ship operated by a Spanish charity.

The vessel went 19 days with close to 100 refugees crammed on board. Italy’s then interior minister Matteo Salvini’s stubborn refusal to allow the rescued into Lampedusa left the boat languishing for days within sight of land.

The charity’s founder Oscar Camps shared videos of the tense situation on board as arguments broke out between the crew, the Italian coastguard and the rescued people. In one clip, nine refugees throw themselves overboard in an attempt to either reach the island or end their own lives.

Eventually, after several emergency medical evacuations, an Italian court ordered the ship’s temporary seizure and brought the migrants to land.

“We also endured a very horrific standoff at the same time as the Open Arms incident,” Bowman reminds me.

At the time, the Ocean Viking was carrying 356 refugees and had also been denied a port of safety by Italy and Malta. Other EU nations ignored its calls for help.

“People were throwing themselves overboard on the Open Arms and we had people threatening to go on hunger strike.

“They were absolutely terrified that we were going to send them back to Libya. They were asking us every day what’s going to happen and where we were going. And we couldn’t tell them anything.

“We had to say we’re really sorry, we don’t know, we’re working as hard as we can, but we promise we won’t take you back to Libya.

“Fourteen days at sea waiting in very cramped conditions in the middle of the summer really pushes people to breaking point.

“These people had been through so much already. And they were now in a situation where they were being told once again that they’re not wanted, they’re not welcome, that people don’t see them as human beings.

“One of the things the crew wondered was how we got into this state. It was only a year ago that the Aquarius was prevented from entering a harbour for just a few days and the world took notice. And now we were weeks on end and it was just commonplace. It was the new normal.”

I ask Bowman how she feels about Europe’s handling of the crisis. She says the overriding emotion is one of sadness.

“We’ve literally just got off the ship, just touched ground for the first time in over three weeks. But for the people that we have rescued, their journey is not over.

“They’re entering into a context where there are a lot of misconceptions about who refugees, migrants and asylum-seekers are. The asylum system process they’re about to go through is incredibly arduous.

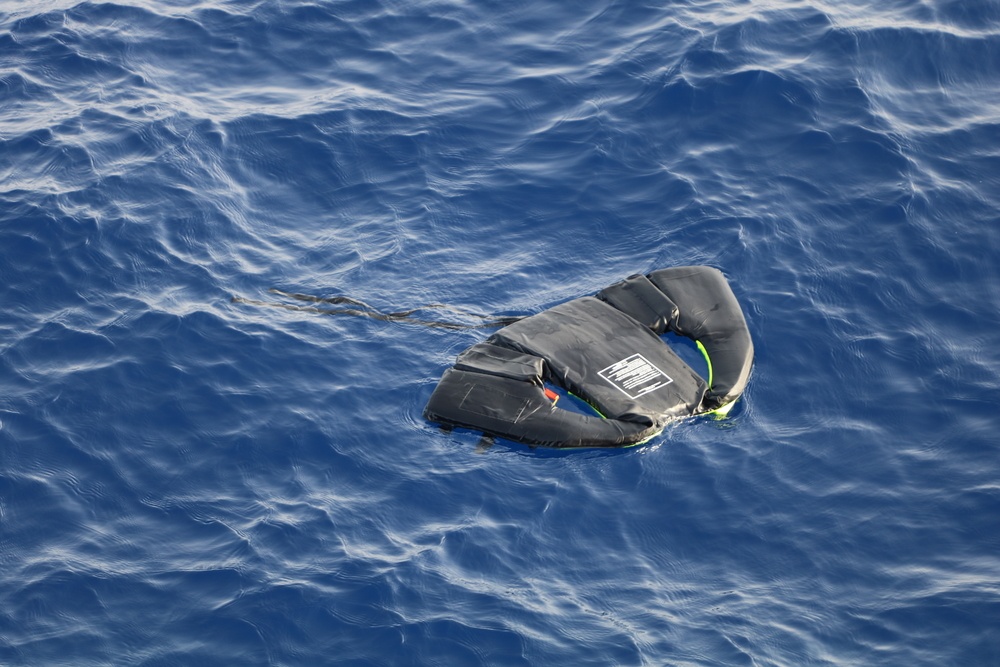

“The fact remains that no-one knows how many people, as I speak to you now, are trying to make that journey across the central Mediterranean. We know it’s the deadliest migratory route in the world, but we don't really know exactly how deadly it is.

“On this last rotation, we had a family: a father, mother and four kids, who’d been detained in Libya. They tried to make the crossing twice previously and had been intercepted by the LCG and forced back into detention.

“They had been treated by MSF while they were in detention, which they were incredibly grateful for because they said there were other people who weren’t as fortunate, who lost children.

“They told me this was their last attempt. They said: ‘Look, we don’t even know what we would have done. Honestly, if we hadn’t made it, then we would rather have been dead in the water. At least then it would be over. At least then we would be able to rest.’

“I understand that is really difficult for people to put themselves in the shoes of an individual for whom their reality is so incredibly removed from their own. But I think we’ve gotten to a point where we’re so lacking in a sense of shared humanity. What world are we creating? Where are we heading?”

It sometimes feels like we’re heading towards a kind of eco-fascism, comes my response. As our ecosystems are increasing devastated by climate change, I worry that it will be those forced to flee from the worst effects that will bare the brunt of, and the blame for, climate destruction.

“We can just keep building the walls higher,” Bowman says, “but they can only go so high.

“Unless we really address the root causes as to why it is these people are forced onto the move, unless we address the situation in Libya and provide legal options in order that they can escape, then nothing is going to change and we’re still going to be a necessity in the central Mediterranean Sea.

“The very organisations, the very people who are simply trying to do the job that Europe has left by removing its search and rescue capacity are also now the organisations and individuals that are being singled out as criminals.”

With alt-right poster boy Salvini no longer in government, perhaps things could change for the civil migrant rescue fleet. Indeed, late last month the governments of Malta, Italy, France and Germany met in Valletta and agreed to set up “regulations for a temporary emergency mechanism” to help Italy and Malta deal with the crisis — note the word “temporary.”

Bowman says it’s too early to tell if any of this will have a positive effect, but she does hold out hope for the future. She says she has to.

“If I didn’t believe we have the possibility to shift the way people see what we do and the way that we deal with one another as humans, I wouldn’t be doing the job that I do.

“The situation now is quite literally leaving people to die at sea. It’s leaving people with a totally impossible choice whereby they are having to decide between staying where they are and suffering or risking their lives at sea.

“I feel the shift will come from civil society, from people once again embracing what it means to be a human being with shared responsibility, with community, with compassion.

“I have to believe that things could be different. And I believe that part of that change comes from people having the tools to understand the reality that is playing out there.”

Hannah Wallace Bowman is a communications manager for MSF.

Ben Cowles is the Morning Star’s web editor. He also co-hosts Podaganda, the podcast the corporate media warned you about, with the Star’s international editor Steve Sweeney.

You can find Podaganda on iTunes, Spotify and online here: mstar.link/Podaganda.

Ben Cowles

Ben Cowles