This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

EVERY year, there are many events held to celebrate the achievements of trade unionists who went before us, such as Tolpuddle where we remember people like George Loveless and his comrades, who were arrested on a February morning in 1834 and deported to Australia to face years of hardship and brutality.

MatchFest too celebrates the achievements of the women of Bryant & May match factory in London, who in 1888 walked out over pay, conditions and bullying by the factory management. Two fine examples of resilience and bravery that are an inspiration to us all.

To those of us who have been involved in taking strike action and have experienced the hardship that it brings, it hits home just how brave it was for those who withdrew their labour, bearing in mind the harshness and social conditions of those times.

Nevertheless, they still chose to do so and faced the consequences. However for some, it wasn’t just the hardship or loss of liberty that they sacrificed for the right to “down tools,” it was their lives, as was the case for two trade unionists from Liverpool in 1911.

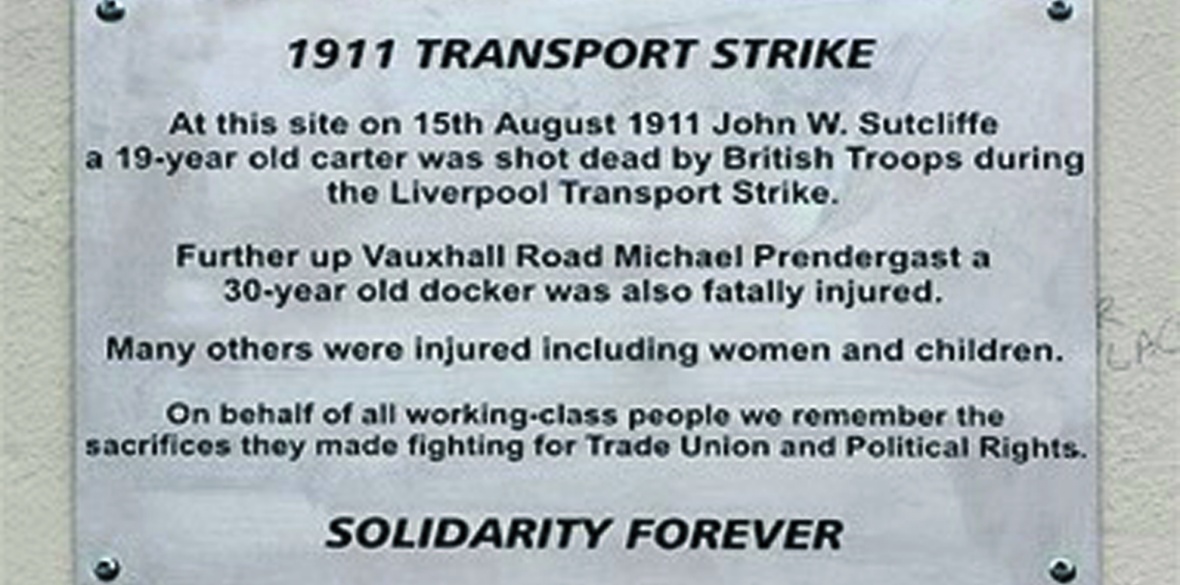

Comrades may be forgiven if the names John Sutcliffe and Michael Pendergast do not ring any bells.

However, for trade unionists in Liverpool, their names are linked with a time in history when total solidarity of the men and women brought the city to a halt, in what became known as the 1911 Liverpool Transport Strike.

The strike, originally began with the seamen in Southampton but soon spread to Liverpool. By August 10 1911, the civil unrest in the city reached such a level that the following a request from the Lord Mayor of Liverpool, home secretary Winston Churchill dispatched extra police from as far as Birmingham and mobilised troops from units including the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and the Hussars. Within days, the city was saturated with over 2,500 police officers and over 5,000 soldiers.

In true political fashion, Churchill dismissed the reports that the violence and unrest were due to industrial action, and instead told Parliament that riots in Liverpool do occur from time to time due to the sectarian divide.

While it’s true there was sectarian violence in Liverpool, in the main related to a large number of families, such as my own grandparents, arriving in Liverpool from Ireland to escape the famine, on this occasion Churchill was wrong.

If anything, the industrial action unified both the Protestant and Catholic community — albeit for a temporary period.

As the situation deteriorated, officials called a mass meeting in support of the strike for Sunday August 13 at St George’s Plateau, situated outside St George’s Hall in Liverpool city centre.

Strike committee leader Tom Mann, one of the most influential trade unionists of that time, reached an agreement prior to the meeting that the police and military presence would be kept to a minimum.

Mann and other union officials also called on those taking part in the rally to conduct themselves with dignity. Unfortunately, what Mann was not made aware of was a large number of police were waiting inside St George’s Hall to be called upon if required.

Although an estimated crowd of 40,000 were expected, it was reported that between 85,000 and 100,000 people attended the rally.

Even for its day, it was a remarkable turnout and show of solidarity that today’s trade union leaders, even with the power of social media, could only dream of drawing.

With no public transport moving, the men, many with their wives and children walked miles from the north and south of the city to listen to the speakers, escorted along the route by pipe and drum bands of both Protestants and Catholics.

In his book titled The Rolling Stonemason, Fred Bower, a Liverpool socialist who was one of the speakers addressing the crowd, described the event as having “a wonderful spirit of humour and friendliness,” with people “all in their Sunday best, many men with their womenfolk.”

Unfortunately, the friendliness described by Bower wasn’t to last for long. Following a minor scuffle between police and a few strikers, the police emerged from St George’s Hall and began to baton-charge the crowd, striking blows at men, women and children, leaving many bleeding and unconscious.

It was estimated that 350 people were injured in the baton charge, prompting the press of the day to label it as Liverpool’s “Bloody Sunday.”

On August 15, as the industrial action tightened its grip, in the north of the city, the 18th Hussars provided an escort for the prison vehicles en route to Walton Prison.

As the crowd attempted to free the strikers from the prison vans, the soldiers opened fire, killing Sutcliffe and fatally injuring Prendergast.

At an inquest into the deaths of the two men, it was suggested that they had not been shot by the soldiers but by a member of the crowd who had been seen firing a weapon.

Just like today, getting justice for unarmed innocent victims killed by crown forces, whether police or army, proved difficult to almost impossible. The jury found that the soldiers were correct in firing their weapons to try to suppress the riot, returning a verdict of justifiable homicide.

However, the deaths of Sutcliffe and Prendergast were not in vain. With the employers prevented from breaking the strike by unionised and non-unionised workers uniting in solidarity, after almost three months, Liverpool was brought to a standstill.

Finally, at a meeting involving the trade unions, railway companies and the government, an agreement was finally reached which included the reinstatement of all sacked strikers.

As a permanent reminder of the ultimate sacrifice made by Pendergast, aged 30, Sutcliffe, 19, and the many others injured on Liverpool’s Bloody Sunday, a memorial plaque, situated in Vauxhall Road, Liverpool was unveiled by Len McCluskey on August 18 2012.