This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

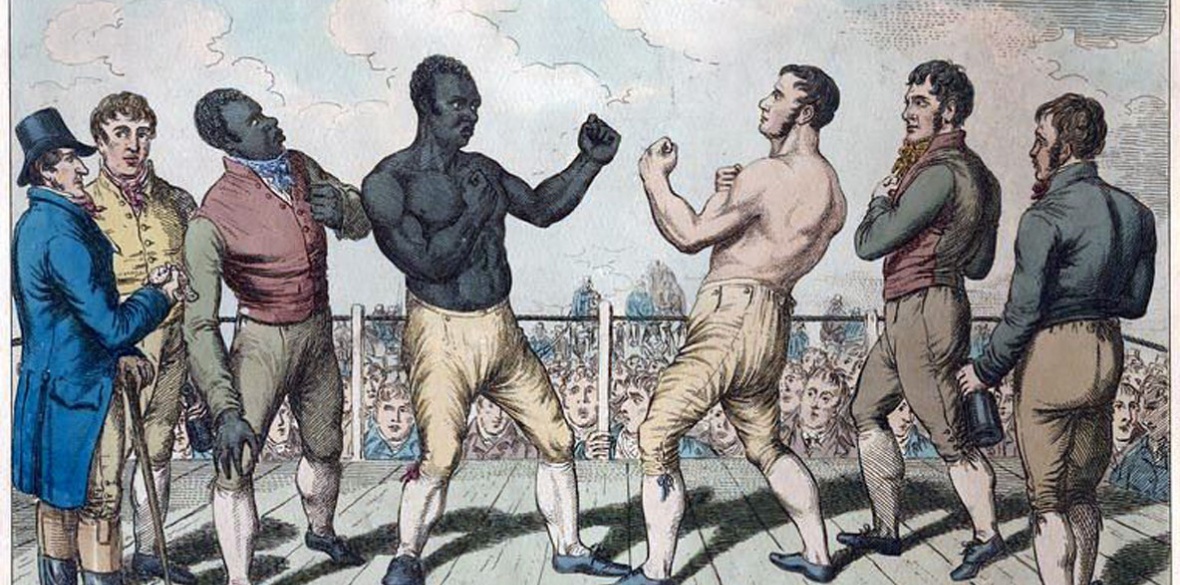

THE first world title fight in boxing — as acknowledged by most boxing historians — took place at Capthall Common in Sussex on December 18 1810.

It was fought between Tom Molineaux, a former slave from Virginia who began boxing when he arrived in New York as a freeman at the age of 20, and English champion Tom Cribb.

The occasion was preserved for posterity in the writing of the most popular English sportswriter of the period, Pierce Egan: “The pugilistic honour of the country was at stake,” Egan wrote, “the national laurels to be borne away by a foreigner — the mere idea to an English breast was afflicting, and the reality could not be endured — that is should seem, the spectators were ready to exclaim…”

The fight lasted 35 rounds. In the 19th, members of the crowd rushed into the ring and attacked Molineaux, who’d made the mistake of daring to outbox his opponent.

The result was the American sustaining a broken finger. But no matter, in the open and in the rain the fight continued, with Molineaux continuing to dominate — until by the start of the 28th round (yes you read that right, the 28th round) Cribb appeared out for the count.

However the judicious employment of time-wasting by the Englishman’s cornermen, who brought proceedings to a halt on the back of allegations of foul play by the American, allowed him to recover.

Cribbs subsequently emerged victorious after Molineaux hit his head on one of the corner posts, forcing him to concede seven rounds later.

Racism was of course key in the ill treatment meted out to Molineaux. He alluded to it in the open letter he published after his defeat, challenging Cribb to a rematch while “expressing the confident hope that the circumstances of my being a different colour to that of a people amongst whom I have sought protection will not in any way operate to my prejudice.”

The rematch took place the following year before a crowd of 15–20,000 people. Tom Cribb again emerged victorious; this time over 11 rounds.

A century later and another champion whose life and career was defined by racism was Jack Johnson. Born on March 31 1878 in Galveston, Texas, he was destined to have a profound impact, not only on the sport of boxing, but American society as a whole.

Both his parents were former slaves — his father Henry of direct African descent. Jack was the second born and the bulk of what little education he received, he received at home.

School he attended only sporadically until starting work on the docks as a labourer in his early teens.

It was there, on the docks, that Johnson was introduced to prizefighting. Realising he had talent for it, he began taking on fellow workers and local hardmen in specially organised match-ups for money donated by spectators in return for a good fight.

The exact number of fights Jack Johnson had has been disputed. The least number cited is 77. Considering that boxing bouts in the early part of the 20th century could go on for 30 rounds and more, the immense physical ordeal he endured in a career that ended at the age 60 in 1938 is remarkable.

His significance in the social and cultural history of the US is rooted in his unflinching defiance of the racial hierarchy that underpinned the nation’s dominant cultural values.

That said, even he was unprepared for the racial hatred directed at him after he defeated heavyweight champion Tommy Burns in 1908 in Sydney, Australia.

The heavyweight title was deemed the exclusive property of the white Anglo-Saxon race and in daring to win it in a one-sided fight, the new black champion instantly became the subject of a moral panic.

Jack London, famed novelist, put out the call for a white champion to wrest the title back from the black impostor who was now holding it. It was he who coined the term the “great white hope,” which endured and remained a part of American sporting vocabulary up until Gerry Cooney was defeated by Larry Holmes in 1982.

Johnson was forced to fight a series of white contenders as a racist US boxing establishment set out to find someone to prove the physical and fighting superiority of the white race. Of the series of fights that followed, his encounter with Stanley Ketchel in 1909 has gone down in history.

It lasted 12 hard rounds, at which point Ketchel connected with a right to the head that succeeded in dropping Johnson to the canvas. As Johnson got back to his feet, Ketchel moved in to finish him off. But before he could unleash another punch he was met with a right hand to the jaw that knocked him spark out.

According to legend, the punch was so hard some of Ketchel’s teeth ended up embedded in Johnson’s glove.

In 1910, one of the biggest heavyweight fights in the history of the sport took place in Reno, Nevada. Billed as “the fight of the century,” it was held in a specially built outdoor arena.

It brought undefeated champion, James Jeffries, out of a six-year retirement to take on the challenge of defeating Johnson and thereby rescuing the title on behalf of white America.

Such were the times, Jeffries was completely unabashed about the fact, announcing in the run-up that he felt “obligated to the sporting public at least to make an effort to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race.”

Johnson proceeded to disappoint both Jeffries and the “white race” when he knocked the former champion down twice on the way to eventual victory in the 15th, when the referee stopped it.

Afterwards, race riots erupted across the country, in the course of which 23 people were killed. In black communities there were also celebrations; Johnson’s victory so significant it was commemorated in prayer meetings, poetry and forever preserved for posterity in black popular culture.

No matter, dogged by an establishment that was determined to put him in his place, the black champion’s personal life saw him tried and convicted for violation of the Mann Act, which prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for immoral purposes.

Perhaps as a consequence of his being so maligned and rejected by mainstream society, Johnson was a man who sought solace in the company of prostitutes, another much maligned demographic.

He was fined and sentenced to prison by an all-white jury. However, defiance still running through his veins, instead of meekly accepting his sentence, he skipped bail and fled to Canada — and from there across the Atlantic to France.

For the next seven years Jack Johnson remained outside the US, moving between Europe and South America. He continued to defend his title, though only sporadically, until finally losing it to Jess Willard in Havana in 1915.

Incredibly, the fight went 26 rounds before Willard KO’d the champion.

Returning to the US in 1920, Johnson was arrested and sent to prison to serve out his sentence.

It was only in May 2018, after a long campaign, that he was finally awarded a posthumous pardon by, of all people, Donald Trump.

Jack Johnson was married three times, on each occasion to a white woman. At his funeral in 1948, a reporter asked Irene Pineau, his third and last wife, what she’d loved about him most. “I loved him because of his courage,” she replied. “He faced the world unafraid. There wasn’t anybody or anything he feared.”