This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

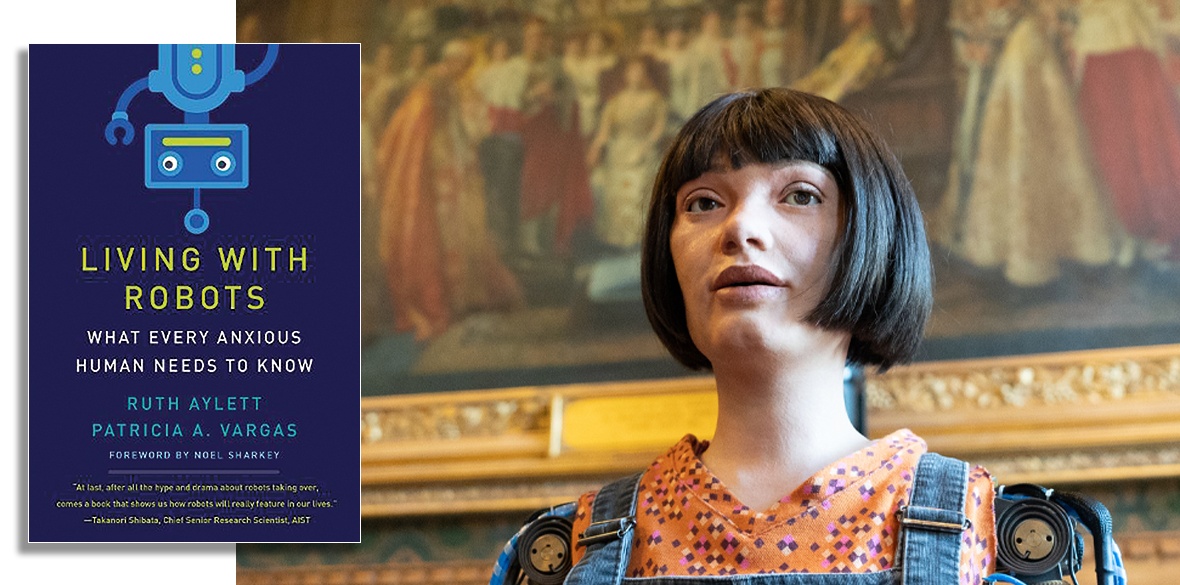

Living with Robots

Ruth Aylett and Patricia A Vargas, The MIT Press, £26

ROBOTS elicit powerful feelings and grandiose claims. Think about their portrayal in cinema: from the artificial agent provocateur of Metropolis (1927) to the benign and self-aware automaton of Interstellar (2014), they have inspired a curious blend of irrational dread and unjustified optimism.

These emotions inform media speculation about autonomous vehicles, slaughterbots, sexbots and industrial androids. A balanced and comprehensible guide to the aspirations, methods and constraints of robotics research is therefore timely and necessary.

Aylett and Vargas begin by examining the 2,500-year history of their discipline: its emergence from the speculations of mythology and fiction, and its implementation in early engineering, particularly in the form of intricate clockwork automata.

This is followed by lucid, jargon-free outlines of important ideas, debates and challenges in robot engineering. Chapters are organised thematically, describing work in areas such as robot sensing, movement, learning, problem solving, collaboration, emotional recognition, ethics and artificial intelligence.

Readers fearing an imminent android apocalypse will find reassurance in the authors’ refutations of media mythology.

The recognition of emotions is “still some way off”; generalised object manipulation is “not anywhere near feasible today”; and speech and language abilities will be “limited — for the foreseeable future.”

Most significantly, it is asserted that researchers “do not currently have any idea” how to make a robot with artificial general intelligence.

This is partly because there is no widely accepted definition of intelligence, but also due to the impossibility of emulating the flexibility of human behaviour or the dynamic complexity of our nervous system with existing technology.

But scepticism about artificial replication of the subtlety and scope of human activity does not render robotics research worthless.

Aylett and Vargas discuss progress in work on robot-assisted search and rescue, the use of industrial “cobots” for repetitive heavy lifting and the development of robotic mobility aids for people with severe disabilities.

In addition, they highlight spin-off benefits in terms of the discipline’s contribution to our understanding of cognition, physiology, social co-operation and neuroscience.

Living with Robots scores highly on clarity and accessibility, but the segment using a cellular automaton to demonstrate the principle of “emergence” (systems becoming more than the sum of their parts) would have benefitted from a supporting diagram or two.

Another flaw is that the book’s reassurances and reality checks stem from its focus on the very near future.

In contrast, Turing Award winner Yoshua Bengio has looked further ahead: his alarm at the pace and direction of research in intelligent systems has led him to demand international regulation of lethal autonomous weapons.

Robotics, like other strands of research in artificial adaptive systems, has the potential to enrich or diminish our lives.

Aylett and Vargas acknowledge the future will be shaped not just by the objectives of their fellow researchers, but also by the social, economic and political context in which their work is undertaken.

Their call for citizens and scientists to work together to deliver a beneficial and liberatory technology is laudable.

And their frank and accessible insights into the technical and ethical aspects of their discipline strengthen the chances of a vital public collaboration being achieved.