This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

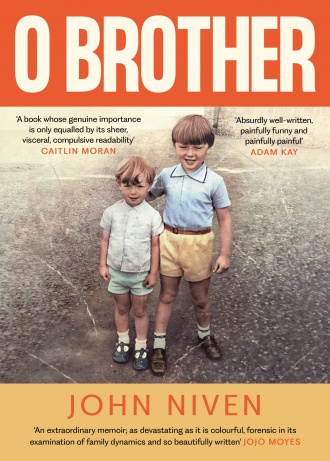

O Brother

John Niven, Canongate, £18.99

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS wrote that the most dangerous word in any language is “brother.”

“It’s inflammatory,” says his lordly character Gutman in Camino Real, a play about a dead-end place surrounded by desert all but cut off from the outside world. The absurdist work depicts a bleak line-up of lost souls in a fallen society to explore themes of captivity and escape, death and rebirth, and the elevation of the spirit.

The parallels with Irvine, Ayrshire, in which the troubled life of John Niven’s younger brother Gary provides the framework for his memoirs, are striking.

This is the true story of a one-horse town in which a man cages himself from childhood in his own lonely labyrinth of psychological complexity, trauma, pain, and substance abuse.

Gary’s personality was inflammatory in every sense, driven by an anarchic, hedonistic energy since boyhood that, despite his many problems, leaves one in awe of a life lived on its own terms as a scorched-earth masterpiece of uncontainable freedom.

The role played by Niven — a Scottish author and screenwriter — is that of the successful older brother racked by guilt over the notion that Gary was not lost, but in fact abandoned, and that he could have somehow helped prevent his sibling’s suicide.

Gary was left brain dead from hanging himself inside a hospital room where he had been taken after a cry for help, his death at 42 not long afterwards probably avoidable and resulting eventually in hard-fought compensation for what, by any account, was gross negligence.

But O Brother does more than self-flagellate, for Niven reveals how he was driven by the same engine of hedonism to escape Irvine and pursue a career in the music industry fuelled by booze and drugs and then, when this ran into the buffers, as a writer.

His keen memory of growing up in a mostly loving working-class family creates a masterwork of colourful detail that many readers will recognise, from the smell of his father when they play-wrestled on the floor to the latter’s rage at Gary’s frequent misdemeanours.

At times hilarious and refreshingly self-deprecating, this book is a character study seeking to account for how the lives of two brothers, and a younger sister Linda, can diverge so dramatically.

Niven is overwhelmed by unanswered questions about Gary’s final days and hours, what he calls “suicide’s plutonium.”

He undertakes an almost forensic search for clues to explain what made his brother the man he became — with “no neat conclusion” — from his birth as a Wednesday’s child “full of woe” and his risk-taking as a boy, to daredevil stunts and a furious temper inherited from their father, a character who looms large in this story.

The suggestion is that it was in early childhood that Gary assumed the traits of attention-seeking and uncontrollable anger that would define his later life as a “bad wee stick.”

Niven writes: “Looking back over all of this now, I see that many of Gary’s attributes as an adult were in place, in miniature, before he was even ten.”

Amid all the hues of growing up, Niven displays his trademark encyclopaedic knowledge of music and popular culture from punk to Britpop: his acclaimed debut novel Kill Your Friends, for example, was set in the record industry.

It is of little consolation to note that the guilt of the living is an inevitable, unavoidable legacy of suicide, and at one level Niven’s book is self-evidently an attempt to exorcise this feeling.

However, it is much more than that, as a rich, witty, emotionally perceptive snapshot of a fallen society of drugs and dregs in a neglected town spoken through the characters’ vernacular “holocaust of language” that pulls absolutely no punches.

Gary is never forgiven for his self-serving behaviour, and there is no attempt to glorify the crimes he committed and the bad crowd he fell in with that led to imprisonment, debt and even theft from his own mother.

Niven paints a picture of a sick man in need of constant attention, but few things happen in a vacuum and we are in little doubt that the malaise was more widespread, with early deaths from sickness, overdoses and suicide claiming many of Gary’s peers.

Younger brothers everywhere who have watched older siblings soar to become the pride of their parents will identify with this tragicomic tale which, when the critical hyperbole has faded, will enter the great bibliography in the sky as one man’s longing epitaph to a departed brother.