This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

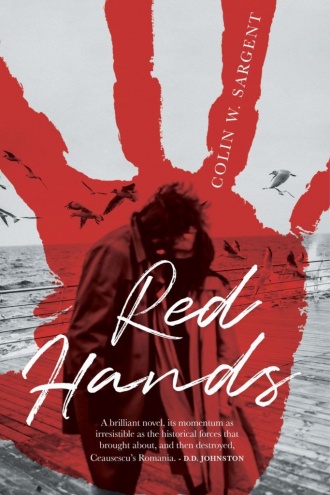

Red Hands

by Colin Sargent

Barbican Press, £12.99

Haz de necaz. The term – Romanian for rueful laughter – fittingly appears a number of times in this novel. It pretty much describes Red Hands’ tone – tragedy hardened further by comedy.

After his extraordinary second novel, The Boston Castrato, Colin Sargent shifts his intelligent and sharp focus from the 1920s USA to the Romania of the 1960s onwards.

Employing a part-autobiographical, part-fictionalised first person account, he empathetically describes the troubled life of Iordana Ceauscescu, wife of Valentin, the eldest child of Nicolae and Elena.

Although increasingly critical of Romania under the wonderfully self-described Danube of Thought and the Mother of the Nation, this is less a comprehensive critique of the Romanian socialist regime than a very personal story of love and loss amidst senior political families.

Herself the daughter of senior communist party members, “Dana” has the temerity to exercise self-agency by marrying Valentin, the most self-contained and least ideological of the Ceauscescus.

Having done so in the face of opposition from both families, but especially against the express instructions of the ironclad Elena, the young couple are pretty much cast out of the Ceauscescu orbit, although not entirely free of the ministrations of the Securitate.

Sargent is at his most skilful and immersive in describing the interior life of Dana as she both seeks to accommodate Elena’s wishes whilst trying to retain the affections of Valentin. The latter, as with all the Ceauscescu children, slowly succumbs to the immense gravitational pull of his parents, causing Dana further humiliation and heartbreak.

Her becoming pregnant, far from reconciling Nicolae and Elena to her, serves only to infuriate the older couple, proof for them that Dana is out of their control. Yet, thanks to a kindly doctor, her son is safely delivered, although the boy is largely ignored by his paternal grandparents.

The book then delves into two supreme ironies: the first purely personal and the second the personal consequences of the political. Firstly, Dana and Elena’s relationship starts to thaw – thanks to Valentin openly having an affair with another woman.

Then, Nicolae and Elena are toppled in the coup of December 1989 – and bearing the name Ceauscescu is a potential death sentence, the subject of much “Haz de necaz” on Dana’s part given her treatment by the family.

Although we know that she and her son survive, Sargent’s description of the street battles and looting in Bucharest are palpitatingly told, fully engaging the reader in the narrowness of their survival.

This is a fine book and an excellent read. But it doesn’t set out to be anything other than a partisan account from Dana’s perspective. Elena and to a lesser extent Nicolae, are reduced, if not to stereotypes, then at least to comedic and two-dimensional entities. The impact of their own hard upbringings and fighting the fascists as young communists, only occasionally peeks out from underneath their propagandised facades.

Paul Simon